Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

OPS Busing, Desegregation and Demographics

-

What factors changed the OPS elementary school demographics from the mid-1970s until now?

-

A 30-minute video informing the public about the background of the court-ordered Omaha Public Schools desegregation and busing program, which started in 1976 and ran through 1999. It includes interviews with key people and footage of Sept. 7, 1976, the first day the program was implemented at OPS, plus footage of the meetings surrounding the plan.

The 1954 U.S. Supreme Court landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, unanimously found racially segregated schools to be unconstitutional and in violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment, but the court failed to provide a remedy to achieve educational equality. Seventeen years later, in 1971, the Supreme Court's ruling in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education unanimously upheld busing school children to desegregate schools. The decision effectively sped up school integration, which had been slow to take root.

On Aug. 10, 1973, the United States Department of Justice filed suit in United States District Court against Omaha Public Schools, alleging that, as a direct result of intentional actions by the school district, the OPS was illegally segregated. On Oct. 11, 1973, the suit was joined by several African American parents claiming racial discrimination in the operation of the school district.

Issues raised by African American parents in 1973 said the current neighborhood school policy was built on and reflected residential racial segregation resulting from public and private discrimination in housing. They also said there was discrimination regarding recruiting and hiring of staff. In the 1972-73 school year, there were 193 Black teachers, and 121 were assigned to schools with greater than 50% of the enrollment being Black. Only 24 teachers were assigned to schools with a 25% or less Black student population. The above Omaha World-Herald photo was taken in May 1979 at the Urban League of Nebraska banquet, where the plaintiff-Intervenors in the school integration case were honored. They include, from left: Lurlean Johnson, Lillie Gunter, Lorraine Patterson, Irene Gunter, Zenola Hilliard, Nellie Webb, and Charlotte Shropshire.

The District Court found that while some of the schools were segregated, this was not the result of intentional acts by the school district and, thus, not unconstitutional. However, on June 12, 1975, this holding was reversed by the United States Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit. The 8th Court found that the intent to segregate was established by several actions of the school district and that the School District did not meet the burden of proving that its intent was other than segregation. According to David Pedersen, who helped with OPS’ legal representation, there was no claim of the quality of education that Blacks received. The focus was on the concentration of race in the schools and what role Omaha Public Schools played. They found that the school district engaged in actions that had a natural foreseeable consequence -- teacher assignments and the construction of new schools in primarily white neighborhoods.

The court of appeals ordered the school district to integrate the schools by the beginning of the 1976-77 school year.

In response to this opinion, the OPS school board appointed a task force to develop a desegregation plan. The task force was chaired by Dr. Norbert Schuerman, who subsequently served as Superintendent of the Omaha Public Schools from 1983 to 1997. The criteria the desegregation plan had to meet:

- Burdens must be borne as equally as possible by Blacks and nonblacks in all geographic areas of OPS.

- Reassignment of students already attending integrated schools must be avoided wherever possible. Integrated schools are those with a 5% to 35% Black enrollment (+ or – 15 percentage points from the then OPS district-wide Black enrollment of 20%)

- If the percentage of Black enrollment is not between 25%-35% in a school, the school’s Black enrollment should not increase above 35% (later changed to 50%)

- If the percentage of Black enrollment is greater than 35% (later changed to 50%) in a school, the school’s percentage of Black enrollment must be reduced to 35% (later changed to 50%).

The board approved the task force’s plan, and it was submitted to the district court on Dec. 15, 1975. The district court approved the plan with some modifications in May 1976. Omaha was the only school system in the country that wrote its own plan. According to Norbert Schuerman, OPS wanted to avoid the mistakes made by other school districts across the country. The goal was to equal the burden between Black and non-Black students, but it was difficult, with 80% of the OPS student population being white and 20% Black at the time.

Under the court-ordered reorganization of elementary schools:

- All schools provide Kindergarten and 1st grade for students in their neighborhood.

- Students in predominantly Black residential neighborhoods attended their neighborhood schools through 3rd grade. In 4th, 5th, and 6th grade, they attended a feeder school in a predominantly white residential neighborhood.

- Students in predominantly white residential neighborhoods would attend a primary grade center (K-3) in a predominantly Black neighborhood in either 2nd or 3rd grade.

- The entire class got on the same bus with their neighborhood classmates, as opposed to a lottery system seen in other school districts across the country.

- Exemptions were made for schools that were already integrated based on the federal mandate, students with special educational needs, or schools that were on the perimeter of the OPS boundaries, making transportation times too long.

- At the elementary level, 5,700 students were reassigned, 2,400 were Black, and 3,300 were white.

Omaha citizens watched as many cities that received similar court orders responded with demonstrations and violence. As the new school year approached, schools planned activities to help familiarize students and ease concerns. Elementary schools held open houses, ran pen-pal programs to introduce students, and planned opening day events. On Aug. 29, 1976, before school opened, schools organized ride-alongs to allow parents the opportunity to participate on the same bus routes as their children. Rumor Control, operated by the Omaha Public Schools, and the Concerned Citizens for Omaha, answered questions from citizens.

Teachers participated in training workshops and took on new teaching assignments. Schools prepped for incoming students. Law enforcement officers were placed on standby, monitoring buses and schools to assist with any conflicts. Despite all the preparation, no one knew what to expect. An Omaha World-Herald advertising supplement had words of encouragement from Black and white leaders in the community.

“The entire Omaha community has a moral and legal obligation to work peacefully, cooperatively, and diligently for a program of educational excellence in an environment of peace and safety,” said Robert L Myers, Myers Funeral home.

“There are those who look ahead to this challenge with fear. Perhaps this is understandable because all unknown experiences cause some anxiety. But let us also see hope that will be instilled in the minds of some youngsters who may have thought the system did not care about their education, and the opportunity for all of us to learn from one another and grow in our understanding of all persons in this community,” shared Ronald W. Roskens, Chancellor of the University of Nebraska at Omaha

On Sept. 7, 1976, the plan was put into action. According to newspaper accounts, Superintendent Owen Knutzen waited with students and helped guide them to the buses and shared confidence in the busing: “This whole thing is going to work fine after the system has been working a while.” Below is an Omaha World-Herald photo taken by Rudy Smith on the first day of busing. Pictured are Jessica Wells, left, and Veronica Howards during lunch at Kellom School.

Carol Ellis, a teacher at Miller Park who was reassigned to Adams School during busing, shared this story with Making Invisible History students in July 2022. “She (her daughter) was a 3rd grader at Adams and bused to Conestoga. She made a friend, Erica. Before Erica came over, she insisted on me buying her new friend a Black Barbie since they had none. She stayed in touch, and they are still friends on Facebook. My daughter said it (busing) took her out of her white, middle-class bubble.”

As Dr. Schuerman shared with MIHV students in 2022, “the only way racism may be minimized is to mix students so they learn, develop and grow together.”

With the opening of the 1984-85 school year, the Court declared the Omaha School District had attained unitary status and was no longer subject to the supervision of the Court. The Court found the District’s desegregation plan met the requirements of the law and determined the School District was capable of operating without direct court monitoring. Legal Aid, representing Black parents, continued to help adjust the plan. In 1997, the Board of Education issued a task force to study the current desegregation plan.

Through public forums, the primary issues identified were:

- Inconvenience to parents and families. Less family involvement in schools. Inability to drop in and talk with teachers. Time constraints because of children in different schools.

- Length of the bus ride. Time lost each day for bused children

- Cost of busing to OPS

- Safety concerns

- No benefit – bigotry and segregation still exist

- A positive value of integrative education for all children

- Students cannot participate in extracurricular activities.

- Has busing achieved the goal of quality and equitable education for all?

Suggestions:

- Increase magnet opportunities – parents want choice

- Release elementary students from mandatory busing

- Require diversity training for teachers

- Looking at the total inclusion of races, not just a black/white issue.

- Equalize busing between whites and blacks. (One year at school for the majority of students discourages parent involvement.) Evaluate the decision to not allow neighborhood students near magnet schools to attend magnet.

- Maintain paired schools but evaluate pairs based on demographic changes.

From these discussions, Omaha Public Schools adopted a controlled choice plan in 1999, laying the framework for what is used in Omaha Public Schools in 2022. The controlled choice plan was a student assignment method designed to give parents the opportunity to make selections from a wide range of schools and to promote diversity in the schools. In a controlled choice plan, a school district is divided into zones, each of which reflects the district’s racial composition. From their zone, parents choose, in rank order, the schools which they want their child to attend. First choices were honored to the extent that they support the integration of the schools. Also, preferences would be given to students who have a sibling at the desired school or who are within walking distance of such a school.

Today, as part of the Student Assignment Plan, Omaha Public School students are guaranteed attendance at their neighborhood school. Every residential address within the district has an identified home elementary school, middle school, and high school (neighborhood school) defined by school boundaries. The School Choice process allows families the opportunity to apply to attend another school within the district. Families may apply to any school in Omaha Public Schools. However, the Student Assignment Plan determines a student's transportation eligibility and placement priority during the school choice process. Students are prioritized in the following order:

- Neighborhood students

- Siblings of students already attending the school

- Students applying to a partner school where they are eligible for transportation

- All other students

Guiding Principles

- Omaha Public Schools is committed to creating diverse learning environments that offer unique curriculum, programs, and opportunities that build upon the interests and talents of students through voluntary school selection.

- The Omaha Public Schools will work to maintain appropriate enrollments across the district in order to provide the highest quality classroom instruction that supports the educational success of all students.

OPS Student Demographics 1974 to 2022

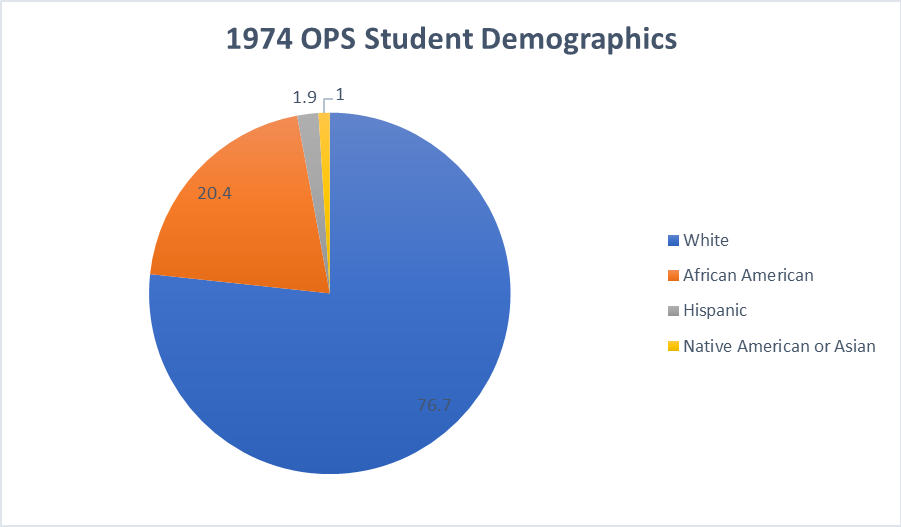

In the Fall of 1974, two years before the implementation of the school desegregation plan, the school district consisted of 75 elementary schools, one middle school, 12 junior high schools, and eight senior high schools. Of the 59,106 students then enrolled, 76.7% (45,309) were white, 20.4% (12,054) were African American, and 1.9% (1,126) were Hispanic. The remaining 1% were Native American or Asian (617).

Most of the African American population resided in an area in North Omaha roughly bordered by Redick Avenue on the north, Dodge Street on the south, 60th Street on the west, and the Missouri River on the east. There was also a significant African American population in a section of South Omaha bordered by Q Street on the north, Harrison Street on the south, 42nd Street on the west, and Gomez Avenue on the east.

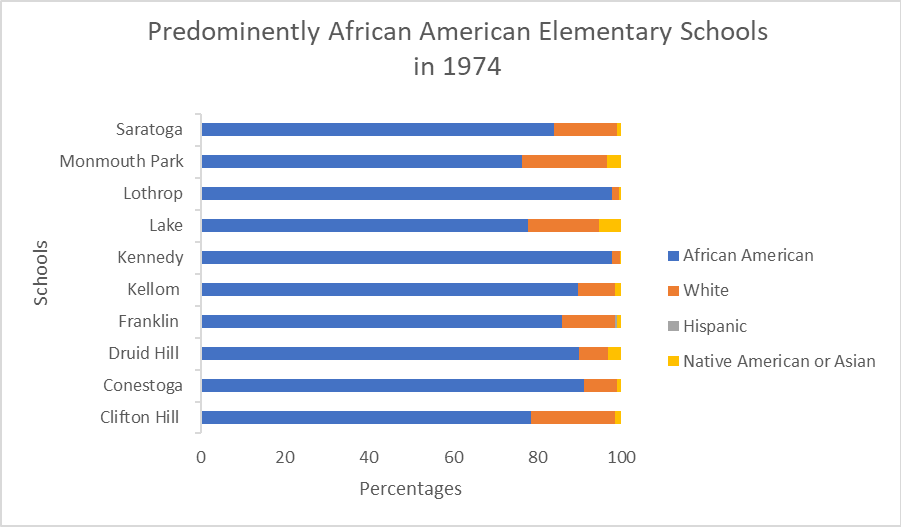

At the elementary level, while there was at least one African American student in all but five schools, African American students were highly concentrated in schools that were predominantly African American. Seventy-five percent of African American elementary school students were attending 13 schools that were greater than 50% African American. Similarly, white students went to predominantly white schools. Eighty-eight percent of white students attended schools that were at least 70% white, and nearly 75% of whites were in schools that were greater than 90% white.

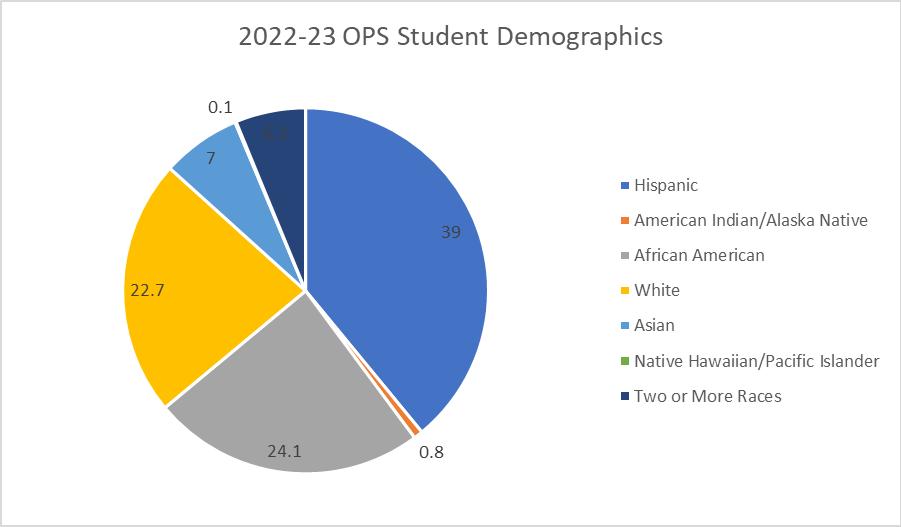

At the start of the 2022-23 school year, the school district consisted of 65 elementary schools, 12 middle schools, and 9 senior high schools. Of the 51,776 PreK-12 students enrolled, 22.7% (11,770) were white, 24.1% (12,501) were African American or Black, 39% (20,200) were Hispanic, 7.0% (3648) were Asian, .8 (393) American Indian/Alaska Native, .1% (64) Native Hawaiian/Pacific Island and 6.2% (3200) two or more races.

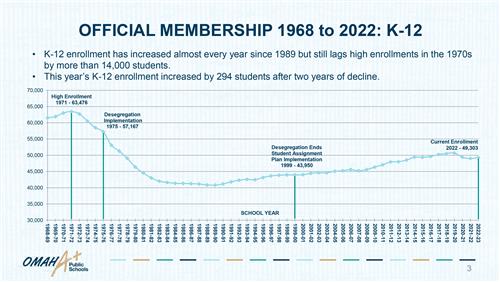

While the African American population has remained relatively the same since 1974, the white population decreased significantly, moving out of the district into the western suburbs of Omaha. The Millard and Westside School Districts were the top two beneficiaries of the white flight. The graph below shows the change in attendance from a high of 63,476 students in 1971 to 49,303 student attendance in K-12 in 2022.

There has been a substantial increase in the Hispanic population. A wave of immigrants from Mexico and Latin America started arriving in Omaha in the 1980s and ‘90s to work in the small, mechanized, non-union packing plants that replaced the closure of South Omaha’s large meatpacking plants in the 1970s. Latinos now comprise more than 10 percent of Omaha’s population. The Latin influence is seen throughout the South 24th Street business district and the Omaha Public Schools in the area.

The Asian population has also grown in OPS, with many Karen refugees settling in Omaha from Thailand and Burma.

Through the current student assignment plan, the Omaha Public Schools is committed to creating diverse learning environments that offer unique curriculum, programs, and opportunities that build upon the interests and talents of students through voluntary school selection. Today, Omaha Public Schools is one of the most diverse school systems in the state.

This site provides a look at all schools across the country and the changes in demographics since 1990.

https://edopportunity.org/segregation/explorer/

2022 MIHV Project

Resources

-

Interviews:

- David Pedersen

- Dr. Norbert Schuerman

- Anni MacFarland

- Casey Hughes

- Carol Ellis

Omaha Public Schools Archives:

- Desegregation Task Force Recommendations to the Superintendent, October 1998

- United States District Court Desegregation Plan for the District of Omaha, May 1976

- The Plan – Desegregation of the Omaha Public Schools, 1981-82

- Research Report #189/Omaha Public Schools – Elementary and Secondary Civil Rights Survey, Department of Health, Education and Welfare, October 1974

- Omaha Desegregation, Advertising Supplement to the Omaha World-Herald sponsored by Concerned Citizens for Omaha, Aug. 26, 1976

Omaha Public Schools – Student Assignment Plan

Omaha Public Schools – Data and Reports

History Nebraska Article on the Desegregation Plan Posted Feb. 24, 2022