Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Escaping the Indignities of Jim Crow

-

In what ways did African Americans create a vibrant social life in a segregated city?

African American Social Life

-

Despite segregation and racism, African Americans in Omaha created a vibrant local culture and found ways to have fun. Some of the unique leisure and entertainment opportunities for local Black people included Kellom swimming pool, a putt-putt golf course, a skating rink and several theaters where local people saw concerts and plays. By looking at entertainment in North Omaha, we can see the many positive ways African Americans built their community.

During much of the 20th century, there was racial tension in Omaha. Many local institutions were segregated, including the Aksarben Ball and Peony Park amusement park. African Americans also were often barred from restaurants, or forced to get their food at the side of the building or use the drive-thru window. But in the midst of all of this negativity, Black people found ways to have fun. They started their own social clubs and held balls as mock imitations of the white balls, and started their own theaters.

Social groups like the Elks and Prince Hall Masonic Lodge started, in part, because local white people would not let African Americans into their clubs, dances and balls. Following the Great Migration, membership in these clubs rose significantly. Even though the Great Depression slowed participation, these organizations continued to sponsor parades and other activities that brought the community together. Some of these organizations and their events continue to this day.

A 6:40 video produced in 2010 interviewing Patricia “Big Mama” Barron and Janet Thomas-Caston.

Omaha Monitor 1920

-

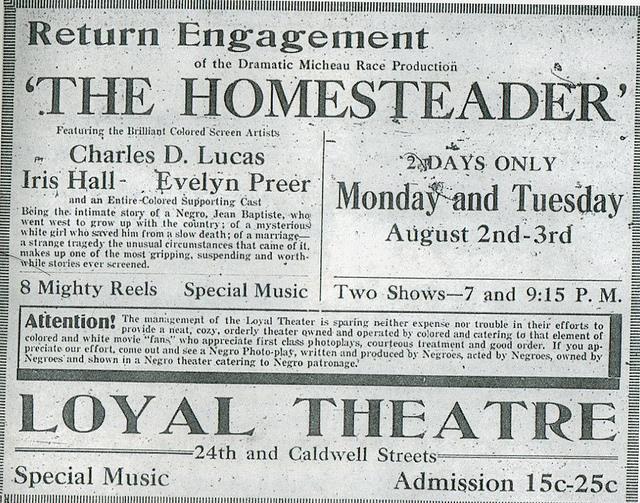

Blacks often advertised their accomplishments in one of the first Black newspapers, "The Omaha Monitor". This is an advertisement for a Negro photo-play, now known as a movie. It was written by Black producer, Oscar Micheaux, and starred African American actors. This showing was at the first and only Negro Theater in Nebraska at the time, The Loyal Theater. (Omaha Monitor)

Elks Lodge Parade 1946

-

The Elks had their 40th annual parade Aug. 18, 1946. Held on North 24th Street, the parade was one of many social events the Elks and other social clubs, including the Prince Hall Masons and the YWCA, organized. The reason that Blacks had to have their own clubs was because the whites would not let them go to their clubs. (Photo courtesy of Douglas County Historical Society)

YWCA LaTeens Social Club 1958

-

The YWCA in North Omaha was founded in the spring of 1920 by Mrs. J. Alice Stewart. The YWCA provided a unique space for young women and girls to get together away from home, to learn etiquette, have fun and just be themselves. Because African American young women were not allowed to attend balls and dances with their white peers, the YWCA sponsored alternative events for them. (Photo courtesy of Patricia Barron)

The Elks Lodge in 2010. The Elks Lodge is still active in North Omaha.

Additional Information

-

Understanding how African Americans spent their free time in a segregated city is vital to fully comprehend the Black community in Omaha, Nebraska. African Americans enjoyed many of the same activities as their white peers, though rarely together. Instead, African Americans were given a designated time to enjoy certain facilities or they built their own entertainment spaces. These spaces were greater than simple fun, though, often building a unique cultural space not allowed in the white mainstream.

African Americans visited theaters, which showed films made by and about African Americans. Filmmakers like Oscar Michauex and African-American owned movie companies, like the Lincoln Motion Picture Company founded in Omaha, gave African Americans leading roles and hoped to counter some of the negative stereotypes often portrayed in white-made films. In Omaha, first the Loyal Theatre and then theaters like the Ritz and Lothrop screened these films for the Black community.

Black social organizations actively involved themselves in the community and provided a space for the Black middle and upper classes to construct a social space. Their role in the community became especially important as the Black community grew during the Great Migration and segregation grew stricter, particularly following the lynching of Will Brown. For example, Nebraska did not form an independent Prince Hall Masonic Lodge until 1919 (local lodges often belonged to Missouri or Iowa organizations before that time). Later, many of these organizations played a role in facilitating the struggle for civil rights in many cities across the United States.

2010 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"I have learned about the invisible history of Omaha that has been right under my nose but I've never known."

— Henessy B.

"I'm really starting to be more interested in history and what Omaha went through to get where we are now."— LaCeiara J.

"The importance of this program was for us to learn about history that is not talked about."— Mahalia M.

Resources

-

Flory, Dan. “Race, Rationality, and Melodrama: Aesthetic Response and the Case of Oscar Micheaux.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 63, no. 4 (Autumn, 2005): 327-338.

Hooks, Bell. “Micheaux: Celebrating Blackness.” Black American Literature Forum, 25, no. 2, (Summer, 1991): 351-360.

Mihelich, Dennis N. “World War I, the Great Migration, and the Formation of the Grand Bodies of Prince Hall Masonry.” Nebraska History, 78, no. 1 (Spring 1997): 28-39.

Mihelich, Dennis N. “Boom-Bust: Prince Hall Masonry in Nebraska During the 1920s.” Nebraska History, 79, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 74-84.

Skotnes, Andor. “‘Buy Where You Can Work’: Boycotting for Jobs in African-American Baltimore, 1933-1934.” Journal of Social History, 27, no. 4 (Summer, 1994): 735-761.

Research compiled by: Hennessy B., LaCeiara J., Mahalia M.