Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Japanese Internment Camps and Education during WWII

-

What might explain why Nisei received better treatment in Nebraska than elsewhere?

The Nisei in Nebraska

-

On Dec. 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and brought the United States into World War II. This led to discrimination against Japanese Americans, especially those living on the west coast. Many Americans feared that Japanese Americans were working with Japan from within the U.S. On Feb. 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which ordered the internment of Japanese Americans living on the west coast. This included more than 100,000 Issei (first generation), Nisei (second generation), and Sansei (third generation). They were then sent to internment camps located from Wyoming to Arkansas. These internment camps were similar to prisons and were often in isolated areas. A few months after being interned, the Nisei began to apply to colleges to continue the education that was taken from them. There were only a few colleges that would accept Japanese students. The University of Nebraska at Lincoln (UNL) was one of these schools. In 1945, the war and the internment of the Japanese ended.

A 6 minute video interview produced in 2015 with Dr. Tom Miya who shares his experience living in an internment camp and attending UNL. Other names mentioned are UNL Nisei students Patrick Sano, Roy Deguchi, Gladys Aoki, Dr. K. George Hachiya and Kaz Tada and Dr. G.W. Rosenlof, who was a major influence in bringing Nisei to UNL. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush gave $20,000 in reparations to each Japanese person interred during World War II. Some of the Nisei UNL graduates chose to donate their reparation money to fund the Nisei Plaza and contributed to scholarship funds.

Nebraska for the Nisei

-

In the Japanese Internment Camps, there were hundreds of Nisei students whose education was interrupted. UNL was one of only a few schools in the country that allowed these students to attend. By the end of the war, UNL had the third largest number of Nisei students in the country. When Nisei students received their acceptance letters from places like UNL, they would be shocked since so many other schools declined them. Many of the Nisei applying would not have a letter of recommendation or even a typewriter. They would write their letter on notebook paper. Patrick Sano, a UNL Nisei student, wrote that when he received the acceptance letter from UNL it was as if it was "God-sent." This could be credited to people like Dr. G.W. Rosenlof, who was a major influence in bringing Nisei to UNL. Many universities had a quota or limit on how many Nisei they would let in; most universities' quota was around 50 students. Rosenlof was able to persuade the chancellor to continue to raise the quota and eventually there were more than 100 Nisei students enrolled in UNL. For example, Patrick Sano was accepted to UNL even though at the time the quota was filled. This was just the beginning of the Nisei's positive experiences in Lincoln.

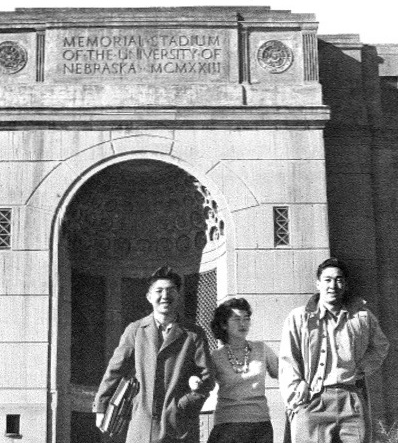

In the Japanese Internment Camps, there were hundreds of Nisei students whose education was interrupted. UNL was one of only a few schools in the country that allowed these students to attend. By the end of the war, UNL had the third largest number of Nisei students in the country. When Nisei students received their acceptance letters from places like UNL, they would be shocked since so many other schools declined them. Many of the Nisei applying would not have a letter of recommendation or even a typewriter. They would write their letter on notebook paper. Patrick Sano, a UNL Nisei student, wrote that when he received the acceptance letter from UNL it was as if it was "God-sent." This could be credited to people like Dr. G.W. Rosenlof, who was a major influence in bringing Nisei to UNL. Many universities had a quota or limit on how many Nisei they would let in; most universities' quota was around 50 students. Rosenlof was able to persuade the chancellor to continue to raise the quota and eventually there were more than 100 Nisei students enrolled in UNL. For example, Patrick Sano was accepted to UNL even though at the time the quota was filled. This was just the beginning of the Nisei's positive experiences in Lincoln. When the Nisei came to UNL, there was a general acceptance of the students, and it was a shock to them to be treated so well after facing so much discrimination on the west coast. Roy Deguchi, part of the Nisei program, was invited to church and even into the home of a Nebraska family. Deguchi believed that this family, who had experienced a loss in the war, showed "the Nebraska spirit." Gladys Aoki, another Nisei student, emphasized how much joy being at UNL brought her. She said that "Kappa Phi brought happiness to my college life when the whole world seemed to have turned against me." UNL also helped Nisei students excel in school and prepare the students for their future. Dr. K. George Hachiya said that "the good Nebraska experience helped erase the bad memories of the relocation and direct me toward the future." Dr. Tom Miya, a graduate from the Nisei program, had a professor at UNL who became his mentor and someone who he looked to for advice all throughout his life. Many of the Nisei were involved in activities and clubs. For example, Kaz Tada, who was in the program at Nebraska Weslyan, was on the Plainsman basketball team and was the senior class president. The Nisei students have shown how much they love UNL and how much the school means to them by donating their reparation money to fund the Nisei Plaza and contributing to scholarship funds. Dr. Miya has given enough money to UNL that he is now part of the Presidents Club.

When the Nisei came to UNL, there was a general acceptance of the students, and it was a shock to them to be treated so well after facing so much discrimination on the west coast. Roy Deguchi, part of the Nisei program, was invited to church and even into the home of a Nebraska family. Deguchi believed that this family, who had experienced a loss in the war, showed "the Nebraska spirit." Gladys Aoki, another Nisei student, emphasized how much joy being at UNL brought her. She said that "Kappa Phi brought happiness to my college life when the whole world seemed to have turned against me." UNL also helped Nisei students excel in school and prepare the students for their future. Dr. K. George Hachiya said that "the good Nebraska experience helped erase the bad memories of the relocation and direct me toward the future." Dr. Tom Miya, a graduate from the Nisei program, had a professor at UNL who became his mentor and someone who he looked to for advice all throughout his life. Many of the Nisei were involved in activities and clubs. For example, Kaz Tada, who was in the program at Nebraska Weslyan, was on the Plainsman basketball team and was the senior class president. The Nisei students have shown how much they love UNL and how much the school means to them by donating their reparation money to fund the Nisei Plaza and contributing to scholarship funds. Dr. Miya has given enough money to UNL that he is now part of the Presidents Club.

Remembering the Nisei

-

In 1994, the Director of Communications for the UNL Alumni Association, Andrea Cranford, arranged a reunion for the Nisei students that attended from 1942-1945. Cranford organized this reunion for the Nisei to remember and reflect on their time at Lincoln and how their lives had changed since World War II.

In 1994, the Director of Communications for the UNL Alumni Association, Andrea Cranford, arranged a reunion for the Nisei students that attended from 1942-1945. Cranford organized this reunion for the Nisei to remember and reflect on their time at Lincoln and how their lives had changed since World War II. Out of the 104 Nisei students in the program, about 30 showed up to the two-day event. People shared their stories about their time at UNL and during World War II. Everyone who was present appreciated the reunion. “It was the most wonderful weekend I’d ever experienced,” Fred Ishii, UNL class of 1946, said. Many of the attendees said that they enjoyed being at UNL and were honored to be recognized by the university. When the reunion was over, a decision for a plot of land on campus for the memorial was decided.

Out of the 104 Nisei students in the program, about 30 showed up to the two-day event. People shared their stories about their time at UNL and during World War II. Everyone who was present appreciated the reunion. “It was the most wonderful weekend I’d ever experienced,” Fred Ishii, UNL class of 1946, said. Many of the attendees said that they enjoyed being at UNL and were honored to be recognized by the university. When the reunion was over, a decision for a plot of land on campus for the memorial was decided. The internment of the Japanese from 1942-1945 took away their privacy, their homes, and their dignity. Almost 50 years later, in 1990, President George H.W. Bush gave $20,000 in reparations to each Japanese person interred during World War II.

The internment of the Japanese from 1942-1945 took away their privacy, their homes, and their dignity. Almost 50 years later, in 1990, President George H.W. Bush gave $20,000 in reparations to each Japanese person interred during World War II. This money was an apology to the Nisei for their internment. Some of the Nisei chose to give their money to UNL. Tom Miya, a student from 1942-1945, donated all his reparation money to the university. He donated it because he loved the school so dearly and UNL helped him achieve his goals. With the money, the university has kept the Nisei memory alive through the Nisei Plaza and scholarships. The UNL Alumni Association announced that the memorial would be located on campus just east of Kimball Hall. There is a plaque that lies on a rock which memorializes these Nisei students. In 1999, the memorial was completed.

This money was an apology to the Nisei for their internment. Some of the Nisei chose to give their money to UNL. Tom Miya, a student from 1942-1945, donated all his reparation money to the university. He donated it because he loved the school so dearly and UNL helped him achieve his goals. With the money, the university has kept the Nisei memory alive through the Nisei Plaza and scholarships. The UNL Alumni Association announced that the memorial would be located on campus just east of Kimball Hall. There is a plaque that lies on a rock which memorializes these Nisei students. In 1999, the memorial was completed.

Nisei - Dedicated Americans

-

Following the events of Pearl Harbor, over 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the west coast were put into Internment Camps. Everyone who went into a camp had to answer a loyalty questionnaire challenging their loyalty to the United States. Even though they had every reason to oppose America, over 300,000 Japanese Americans fought for the United States in WWII. Roughly one out of four Nisei men left the University of Nebraska to fight. While they were in the internment camps, they had the chance to apply to different colleges across the country after the FBI had cleared them.

Many of the colleges rejected them due to their ethnicity or if they had a large military program. The University of Nebraska Lincoln was one of the very few colleges that let them attend; in spite of their large military program, they admitted Nisei students and let them join ROTC. Tom Miya, one of the Nisei that was in the program at Lincoln, stated that when he was registering for classes, the counselor asked if he wanted to join ROTC. Miya did join and later, with many others, voluntarily chose to serve. Even though Executive Order 9066 deemed them an enemy, at least 23 Nisei men from UNL willingly left to serve and help America in WWII.

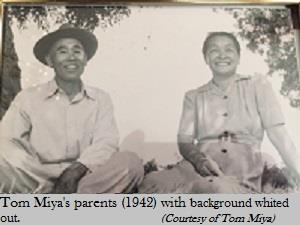

Many of the colleges rejected them due to their ethnicity or if they had a large military program. The University of Nebraska Lincoln was one of the very few colleges that let them attend; in spite of their large military program, they admitted Nisei students and let them join ROTC. Tom Miya, one of the Nisei that was in the program at Lincoln, stated that when he was registering for classes, the counselor asked if he wanted to join ROTC. Miya did join and later, with many others, voluntarily chose to serve. Even though Executive Order 9066 deemed them an enemy, at least 23 Nisei men from UNL willingly left to serve and help America in WWII.Miya proceeded to go to Arkansas for training, while not far away his parents were living in one of Arkansas's two internment camps. In this picture taken of his parents, the background was whited out in order to hide the conditions of the camp. He studied Japanese culture but then was told that he was being switched to another aspect of the war: intelligence. Dr. Miya would drive an hour to the Pentagon to deliver information regarding German and Italian Prisoners of War (POW). Even though at the start of 1942 he was considered an enemy and possibly a spy, he now was working with special intelligence. Likewise, one out of five of all men in the Nisei program at UNL went into some type of military role during World war II.

Additional Information

-

Researching the Nisei—those born to Japanese parents in the United States and educated here—who came to school in Nebraska during World War II presents a gut-wrenching, fascinating, and ironic story. Executive Order 9066 possessed the power to strip thousands of people from their livelihoods and hundreds of students from their educations. The nation that promised life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness was delivering oppression, desperation, and the pursuit of despondency. However, many Nisei students were able to find a future via an education and Nebraska boasted two schools that admitted them: the University of Nebraska at Lincoln (UNL) and Nebraska Wesleyan University. They were welcomed and treated as equals, made friends with the Nebraskans, and were encouraged to join ROTC.

A paradox arises when examining the treatment of Japanese Americans living along the coast and those who resided inland. Some Japanese American students would leave their families in internment camps to attend college. Why then, were these students allowed to leave camp if they were judged as enemies of the state? Conversely, why were they interned if some of them were considered ‘harmless’ enough to leave camp and attend a university? Moreover, if they were truly considered a danger to the United States, then surely they should not have been allowed to enter the military and fight for the U.S.

Part of the answer lies in the distinction the United States made between Nisei—those born and educated in the U.S.—and the Kibei—those born to Japanese parents in the United States but educated largely in Japan. Kibei students were not allowed to attend colleges outside of relocation centers. Alternatively, the Nisei were given greater educational opportunities in the Midwest and East Coast regions after the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council investigated them to ensure they were and would remain loyal to America. More than 4,000 Nisei students were allowed to attend a college or university outside of the camps. They thrived while in college, and many became extremely successful in life. Kaz Tada attended Nebraska Wesleyan and was the editor of the student newspaper, and UNL graduate Tom Miya was a vibrant figure in the world of toxicology and pharmacology both nationally and internationally during his career.

In 1990, the federal government strove to make amends for hard feelings regarding WWII internment by presenting $20,000 to all living interned Japanese Americans. Proving their fidelity to the United States one more time—but more importantly to Nebraska—a few of the Nisei donated their reparation money back to UNL. Nebraska offered asylum for Nisei students from the volatile nature of internment. The memorial forged in their honor reminds Nebraskans of the unfair treatment inflicted upon Japanese Americans during the war and presents a challenging message to retreat from stereotypes and, instead, behave kindly toward all.

2015 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"There are so many stories and events that have shaped Omaha. I think I've learned that Omaha's history is more complex than I ever thought it was. I have changed because I've learned to wonder why. I now won't just look at an old building as an old building. I will look at an old building and wonder why it is there and the story behind it."

— Miranda M.

"MIHV is a really, really fun program with fun things to do! I always look forward to the next day. I can say this summer program is the best one I have ever been to. One of my favorite experiences was going to Lincoln with my group. Before MIHV, I thought history was just another class you had to do to get past school. Now, I look at history a lot broader."- Samantha K.

"The program showed me more sides to Omaha than I thought. I'll have a ton of knowledge about a lot of things that can help me in the future. It's also much more fun than I thought it would be! It's easier to get to know people in this environment. There have been a ton of things I've learned, especially about technology and how to get the most out of it."- Hannah K.

Research compiled by Miranda M., Samantha K., and Hannah K.