Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

African American Firefighters

-

What challenges did Black firefighters face during the Jim Crow era and in the process of integration?

-

Firefighters Mel Freeman and Eli McClinton. The city of Omaha has had a proud tradition of Black firefighters since 1895. (Douglas County Historical Society Archive Photo)

The Untold Story …

-

Omaha has a long and proud tradition of Black firefighters breaking barriers. In 1895, the first Black firefighters were hired. They were very proud of their accomplishments, but they were not treated as equals. Black firefighters had to follow the laws of segregation. They were based at two different fire stations in North Omaha because that is where the Black population was at that time. It was difficult for Black firefighters to be promoted. This started to change in 1951 due to the use of a Civil Service exam for eligibility among applicants. Some challenges to being promoted continued through the desegregation of the Omaha Fire Department.

The Omaha Fire Department was desegregated in 1957. During that year, Black firefighters from the only remaining Black station, Engine Station 14, were moved to other fire stations in the city of Omaha. Then, White firefighters who had volunteered moved into Station 14. When desegregation happened, white firefighters did not accept Black firefighters as equals. Black firefighters were not allowed to eat with White firefighters, sleep in the same beds, or do fire inspections on white property. These things slowly started to change over time.

In 1987, the Omaha Fire Department hired the first class of female firefighters, including the first Black female firefighter, Linda Brown. One big challenge that female firefighters faced was that there were not any women’s locker rooms or restrooms at the stations. Men and women had to share restrooms for a number of years. Also, the male firefighters thought that females were too weak to take on the job and were not taken as seriously as the male firefighters. As a result of this thinking, women had to work twice as hard.

A 6 minute video produced in 2012 with interviews of retired Black firefighters, Marvin Ervin, Bill Johnson (former fire chief), Clifton Wells and Judy Howard (Omaha’s 2nd Black female fire fighter). Ervin and Wells are now involved with the Phoenix Foundation.

-

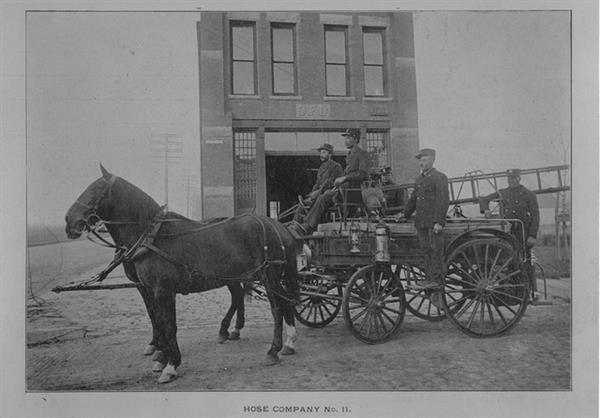

This picture captures the first five Black firefighters that were hired in North Omaha. In 1895, a prominent politician, Dr. Mathew Oliver Ricketts, requested the first five Black firefighters to be hired by the city of Omaha. This was a segregated unit, Hose Company 11. New Black firefighters were only hired if another Black firefighter had died or retired. The need for Black firefighters was significant because there were not enough firefighters in Omaha and no fire stations located in Black communities. White firefighters would not go into the Black neighborhoods such as the Near North Side. The Black firefighters that came onto the job were assigned to the Black neighborhoods. The Black firefighters could not fight the fire from the inside of a house or building if the owner was white.

(Great Plains Black History Museum Archive Photo)

The Process of Desegregation

-

On Aug. 12, 1957, desegregation was implemented in the Omaha Fire Department. This allowed Black firefighters to work in other stations in Omaha instead of having all Black firefighters at one of the two Black fire stations. Just a few days later, the Omaha World-Herald claimed the fire department was fully desegregated, with eight Black firefighters transferred and only three remaining at Station 14. Though the Omaha Fire Department was desegregated, the Black firefighters were not treated equally. For example, Black firefighters could not eat until the white firefighters finished. Also, they could not sleep in the same beds or perform inspections on properties owned by whites. While Station 14, located on 21st and Lake streets, is not used as an operating fire station anymore, the history of what it once was lives on. It is now the headquarters of the Omaha Association of Black Professional Firefighters and the Omaha Black Firefighter Phoenix Foundation.

(Pictured above is Fire Station No. 14, the last station to be desegregated)

Firefighters Battle Injustice

-

In 1942, many white men left their jobs temporarily to fight in WWII, while others retired and remained on the home front. In the Omaha Fire Department, 80 positions opened, creating job opportunities for minorities. Because of a growth in the need for firefighters and more retirements, Black firefighters were allowed to keep their jobs after the war, but failed to receive due promotions. In 1951, three representatives from the Omaha chapter of the NAACP confronted the Fire Commissioner, William D. Noyes, about promotions and advancement within the fire department. The city responded with the Civil Service Ordinance of 1951, which became another driving force for Black firefighters being hired and promoted. Civil Service testing allowed Blacks to have equal employment opportunities. (Captain's uniform courtesy of The Omaha Association of Black Professional Firefighters)

In 1942, many white men left their jobs temporarily to fight in WWII, while others retired and remained on the home front. In the Omaha Fire Department, 80 positions opened, creating job opportunities for minorities. Because of a growth in the need for firefighters and more retirements, Black firefighters were allowed to keep their jobs after the war, but failed to receive due promotions. In 1951, three representatives from the Omaha chapter of the NAACP confronted the Fire Commissioner, William D. Noyes, about promotions and advancement within the fire department. The city responded with the Civil Service Ordinance of 1951, which became another driving force for Black firefighters being hired and promoted. Civil Service testing allowed Blacks to have equal employment opportunities. (Captain's uniform courtesy of The Omaha Association of Black Professional Firefighters)

Omaha's First Black Female Firefighter

-

The first Black female firefighter was added in 1987. Her name was Linda Brown. Forty new firefighters started training on August 17, 1987. Five of those new firefighters were women. Those five were Elisa Nessen, Ann Thomlison, Linda Brown, Denise Riley, and Debbie Robinson. Linda Brown rose through the ranks, quickly becoming the first woman in different areas of the department. In 1990, she became the first female paramedic. In 1997, she was promoted to Captain, becoming the first Black female to reach that rank. Captain Brown retired in 2007 as a fulfilled firefighter.

Additional Information

-

The students’ work in this project highlights important themes in African American history, shining a light on local events that were part of the larger, national narrative. The first theme is the importance of Black self-sufficiency at the turn of the century. In 1895, Booker T. Washington gave his famous Atlanta Exposition Speech, calling on every African American to “Cast down your bucket where you are” and “…dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life…” Whether consciously or not, African Americans in North Omaha exemplified Washington’s goal of self-sufficiency by starting the segregated Hose Company 11 that same year. They were also responding to local circumstances where no fire stations were located in Black communities.

Second, this project also draws attention to the advances of desegregation in the 1950s, while recognizing continuing challenges. In 1954, the Supreme Court famously ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate but equal” had no place in the field of public education. This decision would ripple across other areas of American life. In 1957, the Omaha Fire Department moved to desegregate its ranks. While this was an important event in reducing officially-sanctioned inequality, the students’ work shows that cultural attitudes were more resistant to change. Many white firefighters in Omaha did not believe African Americans were their equals in job performance and maintained segregation in everyday life in the stations.

Third, the students highlighted the importance of equal employment opportunities and the use of affirmative action to remedy past discrimination, a complex and ongoing issue. For decades, discrimination within the Omaha Fire Department favored whites in hiring and promotion and this was certainly true nationally as well. The students discuss how African Americans pushed for the Civil Service Ordinance of 1951 in Omaha, which allowed greater employment opportunities in the Fire Department. However, this is only the first step. It was not until 1971 that the City of Omaha created an affirmative action plan to increase racial diversity in the Fire Department. Moreover, it was not until 1987 that the first women were hired, including Linda Brown, the first Black woman. While affirmative action has been effectively banned in Nebraska by a 2008 measure, groups like the Omaha Black Firefighter Phoenix Foundation, founded that same year, continue to work to recruit and prepare young Black people to be firefighters and first responders.

2012 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"In this camp I have been lucky enough to learn about the history within North Omaha. In order to preserve this history of North Omaha the youth of today must be aware that it exists."

- Sabrina F.

"This program was significant to me because I got to learn more about where I live, my community, and Black History. I think this has helped me because I learned about a history that was lost and about a history that they do not normally teach in class. This experience has helped my identity because I learned about myself and the others around me. This is something that I will carry with me forever."- Courtney S.

"It’s very important that you learn about your past because if you don’t know your past then you will repeat the past. This camp made me realize that I play a big role in my community and anything I do has a big impact on the people around me. One thing I learned about myself was I define myself and I’m proud to be African American."- Bri'Anne W.

Resources

-

"Solution Seen on Firemen." Omaha World-Herald, July 11, 1951.

"Desegregation of Fire Department Finished." Omaha World-Herald, August 8, 1957.

Bosanek, Jim, et al. Omaha Fire Department, 1860-2010: 150th Anniversary. Evans

History Matters. “Booker T. Washington Delivers the 1895 Atlanta Compromise Speech.” https://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/39/

Katznelson, Ira. When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2005.

Landmarks Heritage Preservation Commission. Patterns on the Landscape: Heritage Conservation in North Omaha. Omaha, NE: City of Omaha Planning Department, 1984.

The Omaha Black Firefighter Phoenix Foundation

https://www.omahaphoenixfoundation.com/Omaha_Phoenix_Foundation/Welcome.html

Research compiled by: Sabrina F., Courtney S., Bri'Anne W.