Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Tuskegee Airmen

-

How did the Tuskegee Airmen pave the way for the integration of the U.S. military?

Tuskegee Airmen

-

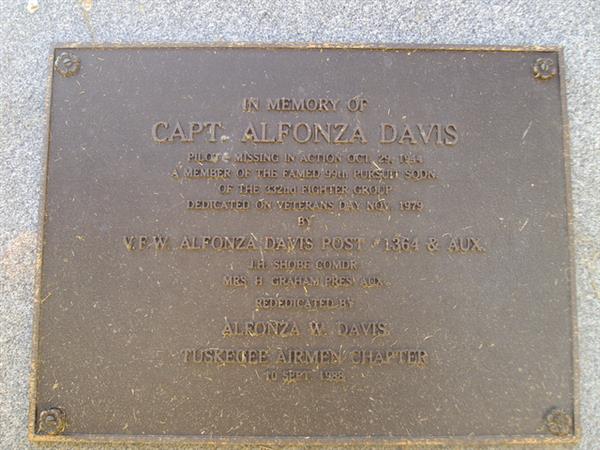

Alfonza Davis Plaque at the Great Plains Black History Museum

Integration Takes Flight

-

The Tuskegee Airmen were heroes in World War II. They were African American fighter pilots of the 332nd fighter group. 450 Tuskegee Airmen served in Europe during World War II, 68 of whom were killed or went missing in action. The main purpose that they served was to escort the bombers into Germany and back. White bomber pilots requested that the Tuskegee Airman escort them because they had gained a reputation for not losing bombers. The Tuskegee Airmen were trailblazers in integrating the Military. They endured the hate of Jim Crow, inside and outside the military, and inspired the start of the integration of the military by order of President Truman in 1948. The Tuskegee Airmen served with distinction, receiving 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, a Legion of Merit, a Red Star of Yugoslavia, eight Purple Hearts, a Silver Star, 14 Bronze Stars, 744 Air Medals, and three Presidential Unit Citations. They also earned a long-delayed Medal of Honor in 2007. As you can see, the Tuskegee Airmen deserve the respect of all Americans.

A 9 minute video with 2012 interviews of Phillip Reis, son of Ralph Orduna, Robert Holts and Charles Lane about their Tuskegee Airman experience. Lane’s comments and stories are especially good.

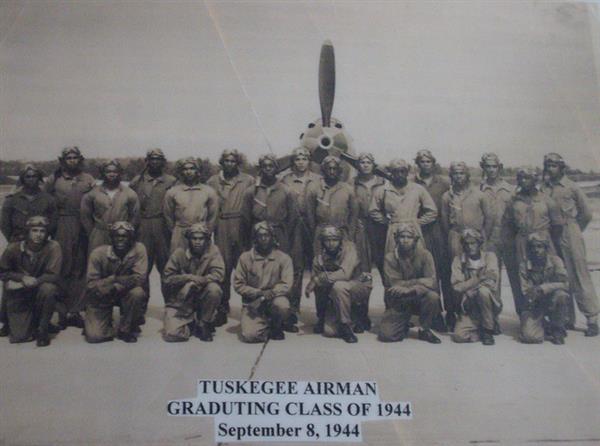

Tuskegee Cadet Class, Sept 8, 1944

-

Cadet Picture: This picture of the 1944 graduating class at the Tuskegee Institute was taken on September 8, before the integration of the military. Col. Lane of Omaha is in this photograph in the back row, 3rd from the right. Despite the widespread discrimination they faced, Tuskegee Airmen formed strong bonds with one another. They were not wanted in the town of Tuskegee. In their own small community, they faced segregation together. This picture symbolizes the Black community in the war. They all identify as Black soldiers in a really tight-knit community because whites in positions of power forced them into a segregated community. This is very significant because they all needed each other, and together they could rise up and prove their equality to white soldiers.

Alfonza W. Davis

-

Alfonza W. Davis was born and raised in Omaha. He grew up in a home on North 29th Street and attended Omaha Technical High School. He was an excellent student and graduated as the class valedictorian in 1937. In March of 1941, Davis enlisted in the US Army. After about a year in the army, Davis was accepted to the Tuskegee Airman program. By March of 1943, only two years after he entered the service, Davis received his officer commission. Captain Davis became the deputy group commander, making him second in command to Col. Benjamin O. Davis in 1944. As a pilot with the Tuskegee Airmen, Capt. Davis was stationed at Ramitelli Airfield in Italy during World War II. He flew a P51 fighter plane on a variety of missions. Capt. Davis went missing during a mission over Italy in 1944 and was later declared killed in action. Before Capt. Davis died, he became one of the great pilots of World War II as the leader of five attacks, one of which destroyed 83 German aircraft. Captain Alfonza W. Davis is significant to the Omaha community as the first Black Omahan to receive his wings. Although he died at the age of 24, his accomplishments as a student, soldier, and pilot made Capt. Davis a person that we can look up to as a role model. Through his accomplishments, Capt. Davis made an impact on the whole world and helped to earn respect for African Americans in a time of segregation.

Alfonza W. Davis was born and raised in Omaha. He grew up in a home on North 29th Street and attended Omaha Technical High School. He was an excellent student and graduated as the class valedictorian in 1937. In March of 1941, Davis enlisted in the US Army. After about a year in the army, Davis was accepted to the Tuskegee Airman program. By March of 1943, only two years after he entered the service, Davis received his officer commission. Captain Davis became the deputy group commander, making him second in command to Col. Benjamin O. Davis in 1944. As a pilot with the Tuskegee Airmen, Capt. Davis was stationed at Ramitelli Airfield in Italy during World War II. He flew a P51 fighter plane on a variety of missions. Capt. Davis went missing during a mission over Italy in 1944 and was later declared killed in action. Before Capt. Davis died, he became one of the great pilots of World War II as the leader of five attacks, one of which destroyed 83 German aircraft. Captain Alfonza W. Davis is significant to the Omaha community as the first Black Omahan to receive his wings. Although he died at the age of 24, his accomplishments as a student, soldier, and pilot made Capt. Davis a person that we can look up to as a role model. Through his accomplishments, Capt. Davis made an impact on the whole world and helped to earn respect for African Americans in a time of segregation.

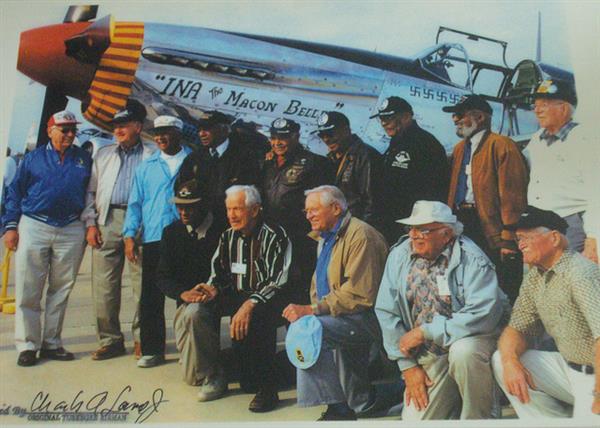

The Reunion

-

The Reunion: This picture was taken long after the end of World War II. It is a picture of Black fighter pilots and white bomber crewmembers that served in the war. The Black men were Tuskegee Airmen, including Col. Charles Lane of Omaha. The white men were bomber pilots who depended on escorts from the Red Tails. This was unusual because, during World War II Black and white men were usually not friendly with one another. In that era, there were two different communities in the military, the Black community and the white community. White and Black soldiers were segregated and Black soldiers faced regular discrimination. This picture, which features both Black and white veterans together, illustrates how much has changed in terms of race relations since WWII. The efforts of the Tuskegee Airmen played an important role in helping to bring about those changes, inside and outside the military, over the 50 years following the war.

Congressional Gold Medal

-

On March 28, 2007, Congress awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to the Tuskegee Airmen, more than 60 years after the end of World War II. Some 300 pilots and family members received the award. The Congressional Gold Medal is awarded to "an individual who performs an outstanding deed or act of service to the security, prosperity, and national interest of the United States". Because Congress, which represents the nation as a whole, gives the award, it is a long-overdue acknowledgment by society of the important and historic contributions of the Tuskegee Airmen.

On March 28, 2007, Congress awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to the Tuskegee Airmen, more than 60 years after the end of World War II. Some 300 pilots and family members received the award. The Congressional Gold Medal is awarded to "an individual who performs an outstanding deed or act of service to the security, prosperity, and national interest of the United States". Because Congress, which represents the nation as a whole, gives the award, it is a long-overdue acknowledgment by society of the important and historic contributions of the Tuskegee Airmen.

Additional Information

-

African Americans have a long history in the military that stretches back beyond the Tuskegee Airmen of WWII. Black Americans have fought in every war in which the United States has participated. With every conflict came a new hope that Blacks would emerge with an improved quality of life in America. They hoped to show their patriotism and prove their competence and bravery to whites. Despite valiant service, African Americans were repeatedly denied rights and respect even after risking their lives for their country.

“All-colored regiments” were used in the Civil War and were reorganized and used during the Indian Wars and the Spanish American War. These units were comprised of all-Black troops led by white officers. During World War I, Blacks were drafted disproportionately into service. Most of the 350,000 African American troops that were conscripted were placed in support roles. In comparison to the generally discriminatory attitude of the white population of the United States, white people in France were more appreciative of the service of the Black soldiers. African Americans were awarded the Legion of Honor by the French government.

As a result of Black soldiers’ service in WWI and pressure from civil rights groups, the Army began training Black officers in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1917. When World War II broke out, Black newspapers and activists pressured the government to utilize African Americans as pilots. The War Department eventually created the 99th Pursuit Squadron near Tuskegee, Alabama. They referred to it as “The Experiment” and the Tuskegee project was expected to fail.

By July of 1942, the Tuskegee Institute had commissioned 33 second lieutenants, but the group had to wait months to be shipped overseas. No white commander wanted an all-Black squadron. Once again, Black newspapers and the NAACP had to pressure the War Department. The Tuskegee Airmen were finally assigned to North Africa and later to Italy. In Italy, the airmen began escorting bombers into Germany and earned a reputation for never losing a bomber. The Tuskegee Airmen’s performance was later utilized as justification for the integration of the military in 1948. More than six decades after their service in WWII, the Tuskegee Airmen received the prestigious Congressional Gold Medal in 2007.

2012 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"Learning about this community is significant because a lot of people don't understand all of the good things going on here. The news identifies North Omaha as a crime-filled area, but it really has a lot of rich cultures that the community needs to know about."

- Jack E.

"This camp showed me how many histories are invisible. This camp is significant because it showed me to never leave those stories behind."- Jennifer C.

"Learning about Omaha's history was a lot more fun than I expected. I liked how we didn't just look in a book for our answers, we went out and found them. This history is always there, you just have to take the time to find it."-Shaundra S.

Resources

-

Bryan, Jami. “Fighting for Respect: African-American Soldiers in WWI.” Military History Online. 2003.

https://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/wwi/articles/fightingforrespect.aspx

Carter, Herbert E. “The Legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen.” National Forum 75:4 (Fall, 1995): 10.

Douglas County Historical Society. Omaha, NE.

Francis, Charles E., and Aldoph Caso. The Tuskegee Airmen: The Men Who Changed a Nation. Wellesley, MA: Branden Books, 1997.

Library of Congress. African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship. March 21, 2008.

https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/aaohtml/exhibit/aointro.html

Tuskegee Airmen, Inc.

Research compiled by: Jack E., Jennifer C., Shaundra S.