Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

-

How did contact with white settlers affect population, health, the economy, and ecology on Native American lands?

Early Contact Along the Missouri

Fur Trade / Early Contact

-

Lewis and Clark's Corps of Discovery opened the Missouri Valley to the American fur trade. Within a few years, French-American traders such as Peter Sarpy and Lucien Fontenelle traveled upriver and set up posts among tribes such as the Omaha, Otoe, Missouri, and Ioway. These trappers and traders typically intermarried with local tribes (regardless of their marital status back in New Orleans or St. Louis) in order to form business partnerships and foster family allegiances. Valuable beaver pelts gathered at American Fur Company posts such as Fontenelle's (Bellevue) and Cabanne's (Florence) helped to establish John Jacob Astor as the United States' first millionaire. By the 1820s, Fort Atkinson, the westernmost point of American settlement, sat on the site of Lewis and Clark's council bluff. Atkinson protected the fur trade and also received the first steamboats on the Missouri River.

Despite the relative peace between Native Americans and the tiny trading posts, the local native population was devastated by a series of smallpox epidemics during this period. Furthermore, unscrupulous white traders introduced whiskey to the local tribes as a form of trade coercion. Eventually, the local beaver population was hunted to extinction. French and Native "half breeds" (also known as Metis) often became major leaders of early Nebraska towns such as Bellevue. Treaty negotiations in the mid 19th century would eventually move the Omaha tribe northward and shrink their lands, but overall the first three decades of the 19th century were one of trade, cooperation, and exchange in the area that would one day become Douglas and Sarpy Counties.

Want things from Native Americans? What would you trade?

-

At trading posts on the Missouri River, French and American traders exchanged beads for things that could help them settle and goods to send back to their commanders in St. Louis. When the hunters gathered enough furs, especially from beavers, they gave them to their wives so that they could prepare the pelt. Using the brains of the animal to treat the pelt made the pelts smoother and longer-lasting. After smothering the pelts with brains, the wives would get a stack of 50 pelts and canoe them upriver to take them to the nearest trading post.

At trading posts on the Missouri River, French and American traders exchanged beads for things that could help them settle and goods to send back to their commanders in St. Louis. When the hunters gathered enough furs, especially from beavers, they gave them to their wives so that they could prepare the pelt. Using the brains of the animal to treat the pelt made the pelts smoother and longer-lasting. After smothering the pelts with brains, the wives would get a stack of 50 pelts and canoe them upriver to take them to the nearest trading post.The Native Americans wanted beads and metal goods, while the Americans and French wanted animal pelts for clothing and hats. The most traded item was beaver fur and beads for Native American moccasins and decorations. Some people decided to trade alcohol to Native Americans even though they knew that the Native Americans didn’t handle alcohol very well. Some fur traders got married to Native American women. Intermarriage helped these early settlers become friends and form partnerships with various tribes. Sometimes, to become friends, American and French fur traders would trade tobacco and smoke "peace pipes" with local chiefs to form partnerships and get better deals while trading.

Jean Pierre Cabanne (Cah-Bah-Nay): A Friend to Native People

-

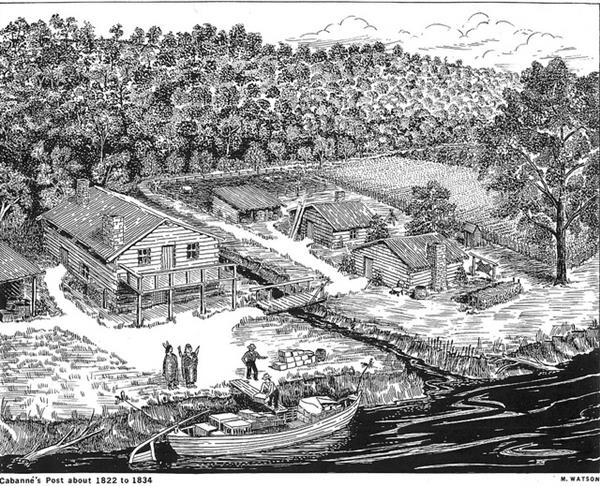

For more than a thousand years, Omaha Native People lived near what is today the Missouri River. Living in earth lodges, they used the river for hunting, fishing, transportation, and farming (From the Nebraska Palladium, July 15, 1854). In the early 1800s, whites began trading with the Omaha and Otoe people for animal fur. In 1822, Jean Pierre Cabanne established a trading post for this purpose.

For more than a thousand years, Omaha Native People lived near what is today the Missouri River. Living in earth lodges, they used the river for hunting, fishing, transportation, and farming (From the Nebraska Palladium, July 15, 1854). In the early 1800s, whites began trading with the Omaha and Otoe people for animal fur. In 1822, Jean Pierre Cabanne established a trading post for this purpose.At Cabanne’s post, near present day Dodge Park, Omaha Indians traded for essential items. Metal goods, beads, weapons, and alcohol were traded in return for beaver and buffalo fur. Because so many native people had become addicted to alcohol, Cabanne restricted its sales starting in the 1830s. Joshua Pilcher, an alcohol smuggler and landowner, tried to smuggle a shipment of alcohol to be sold to Native Americans. Cabanne stopped him by shooting his cannon across the bow of his boat and taking the whole shipment. Because of his interference, Cabanne was fired by John Jacob Astor and the trading post was closed in 1840.

Cabanne’s Post was important because it helped both white and Omaha native people to trade and get needed items. It is a symbol of friendship because they helped each other be successful. Built without a protective palisade, the trappers who lived and worked at Cabanne’s Post felt safe interacting with the native people.

Fort Atkinson: A Position of Importance

-

Constructed in 1820, Fort Atkinson once contained more than 1,000 American soldiers patrolling and living in the barracks. At least the same number of local Native Americans camped nearby, trading with the soldiers for goods and guns. Since the fort was right next to the river, the soldiers decided to farm most of their food. They also traded for furs and hunted for some of the meat they ate. The three nearby tribes were the Otoe, Omaha, and the Ponca. They all gathered from time to time at the fort to sign treaties with the local Indian Agent, the U.S. government ambassador.

Fort Atkinson was built on the side of the bluffs because the great view allowed the soldiers to keep track of what went up and down the Missouri River. Fort Atkinson’s location in proximity to three tribes was important to make sure that they were able to communicate and trade with each other. Fort Atkinson never needed to be defended from any wars or battles because they had good relationships with everyone around them. The soldiers built Fort Atkinson with cottonwood, because it was the only lumber available for them and brick was just too expensive. They didn’t know that cottonwood rotted easily, a fact that would lead to the fort's rapid deterioration, forcing the soldiers to abandon it after only seven years.

Though most native and white interactions were peaceful at this time, in 1824 a misunderstanding between the Arikara and some whites near Souix City led to the deaths of several fur trappers. In response, Fort Atkinson soldiers traveled upriver 300 miles and fought the Arikara under the command of Colonel Henry Leavenworth. The Lakota (Sioux) joined with the American forces and won the battle. Fort Atkinson soldiers never engaged in combat with Native Americans after that.

The photo below shows the Council Bluffs and the chimneys of Fort Atkinson as artist Karl Bodmer saw them in 1833. Courtesy of Fort Atkinson State Historical Park

Big Elk: The Last Full-Blooded Chief

-

In the 1810s, French and American settlers began moving into the Native American land around what is today Omaha. In the Omaha area, whites and native tribes made peace through trading and treaties. Most of the treaties concerned who would be able to use and own the land around the Missouri River. Not everything was peaceful for the Omaha and whites. When the white settlers came, they brought a disease called smallpox that would kill millions of Native Americans, including almost 90 percent of the Omaha tribe. Also, the Omaha people did have conflicts with the Lakota (Sioux) people of the Dakotas. Big Elk, the last full-blooded chief of the Omaha tribe, would lead his people through these changing times.

In the 1810s, French and American settlers began moving into the Native American land around what is today Omaha. In the Omaha area, whites and native tribes made peace through trading and treaties. Most of the treaties concerned who would be able to use and own the land around the Missouri River. Not everything was peaceful for the Omaha and whites. When the white settlers came, they brought a disease called smallpox that would kill millions of Native Americans, including almost 90 percent of the Omaha tribe. Also, the Omaha people did have conflicts with the Lakota (Sioux) people of the Dakotas. Big Elk, the last full-blooded chief of the Omaha tribe, would lead his people through these changing times. Although there were other Omaha chiefs after him, Big Elk, Ong pa tonga in his native tongue, was the last to have only native parents. During a time of great changes, Big Elk wasn’t afraid to speak out for his tribe. He had a powerful ability to bring white and native people together through his voice. Famous for his speeches, Big Elk traveled to Washington D.C. in 1821 and 1837 to tell the American government that his people cared about the land. He also asked for help in the conflicts with the Lakota. Toward the end of his life, he moved his people from Omaha to Bellevue to keep them safe. In 1846, Big Elk died from smallpox.

Although there were other Omaha chiefs after him, Big Elk, Ong pa tonga in his native tongue, was the last to have only native parents. During a time of great changes, Big Elk wasn’t afraid to speak out for his tribe. He had a powerful ability to bring white and native people together through his voice. Famous for his speeches, Big Elk traveled to Washington D.C. in 1821 and 1837 to tell the American government that his people cared about the land. He also asked for help in the conflicts with the Lakota. Toward the end of his life, he moved his people from Omaha to Bellevue to keep them safe. In 1846, Big Elk died from smallpox.

There are some questions about the chiefdom of Big Elk. Different sources claim that Big Elk may have been a “paper chief.” A paper chief is a native who was selected by the U.S. government as a spokesman for the tribe. There may have been other chiefs alongside Big Elk. In a speech to President James Monroe, Big Elk says that “I am a chief, but not the only one in my nation; there are other chiefs who raise their crests by my side.” He also says that “I was often reproached for being a friend, but when my father (whites) came amongst us he strengthened my arms and I soon towered over the rest.” (Big Elk, Feb. 4, 1822)

Big Elk brought whites and the Omaha people together through his peace treaties with the American government. Through his speeches, he became a symbol of peace for his people. Big Elk died in what is today Bellevue, near his grandson, Logan Fontenelle's settlement. He received a Christian burial. Today his gravesite memorializes his accomplishments and reminds us that he was a figure who brought whites and Native Americans together.

(Karl Bodmer paintings courtesy of Joslyn Art Museum. Special thanks to Dennis Milhelich, Gavin Flint, Fort Atkinson State Historical Park, Nebraska History Museum)

Additional Information

-

The interactions between Native Americans and Europeans in pre-statehood Nebraska can often seem like an invisible history. Though a few French-sounding place names have trickled up from this period, the extent to which local tribes and the French Creoles of the frontier helped to shape this area in the decade after the Louisiana Purchase is not well understood or appreciated by contemporary Nebraskans. Nor is it generally well known the extent to which the fur trade transformed native societies through the introduction of metal goods, muskets, and glass beads.

The generally peaceful trade relationships and pragmatic intermarriages of this region left few marks on a frontier history that is so often focused on strife and violence. Indeed, the entire culture of the early 19th century Missouri Valley bears little or no resemblance to our “cowboy and Indian” preconceptions about Nebraska history. Rather, the Omaha area was a home to multi-racial (metis) families such as the Fontanelles, aristocratic European visitors such as Prince Maximilian, and Fort Atkinson soldiers who spent more time studying corn-growing techniques than fighting with local tribes.

The trading posts that sprung up in Sarpy County rapidly evolved into the town of Bellevue, which still celebrates its status as Nebraska’s oldest city, but the North Omaha sites of Lisa’s and Cabanne’s Posts are only remembered through one lonely historical marker (see Cabanne’s Trading Post above) on a stretch of highway near Dodge Park. The period is best remembered through the Fort Atkinson State Historical Park in Fort Calhoun, where the 1820s fort has been painstakingly re-created. However, the memory presented there is largely that of the white soldiers who thought of their post as the edge of the world, and not the Otoe and Omaha tribes who called it home.

The early 19th-century Missouri would be all but impossible for us to picture if it had not been for a Swiss artist named Karl Bodmer who passed through this area while serving as Prince Maximilian’s expedition painter. In a very real sense, Bodmer’s paintings render this invisible history visible. Nowhere does this seem truer than in The Bellevue Agency Post of Major Dougherty, a watercolor from 1833 that depicts the Indian agency and trading post that used to stand in what is today's Fontenelle forest. Here we see what may be the first depiction of modern Nebraskan society and, significantly, Native Americans are in the foreground.

In an era when most European and American painters dismissed Native Americans as either “noble savages” or a menacing presence, Karl Bodmer seemed determined to depict the original peoples of the Missouri Valley as they were. The humanity, pride, and individualism of Bodmer’s portraits of local chiefs speak more clearly about this period than perhaps any other document or artifact. Fortunately for area educators and students (or anyone else interested in this period), the world’s largest collection of Karl Bodmer’s work is located at the Joslyn Art Museum, where an entire gallery is dedicated to his journey up the Missouri, as well as to the incredible Native American arts and handicrafts of the same era. Through art, any history, no matter how obscure, can become tangible: this is why I would like to single out Bodmer as an integral component and helpful contributor to this Making Invisible Histories Visible project.

Thanks to Karl Bodmer.

2014 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"I thought we were going to interview Native Americans, but in my group, we interviewed a historian and we went on tons of field trips. I learned that most Native Americans made peace with the whites by trading and through peace treaties. My favorite experience was going to Lincoln and running up the steps of the capitol building."

- James S.

"I thought this program was going to be boring, but this program is actually interesting and fun. I learned a lot about Fort Atkinson, Big Elk, and the Fur Trade. This program is important because if you know more about the past then you're better prepared for the future."- Makenzy N.

"At first I thought we were all going to be in a classroom in Metro using a computer and finding information. In reality, we still had to use computers to find information but we had fun with the field trips and guest speakers. I've learned more about Native Americans and how they had to live and learn with the American settlers. Every time I see a dent in the ground now the first thing that comes to my head is that it is a decayed earth lodge."- Ari M.

Research compiled by: James S., Makenzy N., Ari M.