Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

The Past and Present of Q Street: South Omaha and the Union Stockyards

-

How did the Union Stockyards, including its rise and decline, impact the economy and culture of the 30th and Q area?

-

The stories of South Omaha’s neighborhoods are inextricably linked to the rise and fall of the stockyards and packing plants that developed in the area. From the late-19th century into the mid-20th century, these industries prospered and South Omaha became known as “The Magic City”, because it seemingly boomed overnight. Often referred to as the lifeblood of South Omaha, these industries were intertwined with the economy and culture of the entire community, which included Polish, Czech, Irish, and German ethnicities. The Union Stockyards attracted white European immigrants, as well as African Americans from the South, to work in often brutal, but well-paying, industrial conditions. At its peak in the 1950s, Omaha’s Union Stockyards surpassed Chicago and Kansas City to become the largest stockyards in the nation. As these industries grew, vibrant ethnic communities and commercial districts sprung up and thrived in the surrounding areas along 16th Street, 24th Street, and in the Saint Mary’s neighborhood at 30th and Q streets.

The stories of South Omaha’s neighborhoods are inextricably linked to the rise and fall of the stockyards and packing plants that developed in the area. From the late-19th century into the mid-20th century, these industries prospered and South Omaha became known as “The Magic City”, because it seemingly boomed overnight. Often referred to as the lifeblood of South Omaha, these industries were intertwined with the economy and culture of the entire community, which included Polish, Czech, Irish, and German ethnicities. The Union Stockyards attracted white European immigrants, as well as African Americans from the South, to work in often brutal, but well-paying, industrial conditions. At its peak in the 1950s, Omaha’s Union Stockyards surpassed Chicago and Kansas City to become the largest stockyards in the nation. As these industries grew, vibrant ethnic communities and commercial districts sprung up and thrived in the surrounding areas along 16th Street, 24th Street, and in the Saint Mary’s neighborhood at 30th and Q streets.During this time, South Omaha prospered and businesses including bakeries, bars, department stores, and restaurants opened along Q Street and 24th Street to accommodate all of the farmers and stockyard workers. Along with this, workers and their families settled around the Union Stockyards and formed many of South Omaha’s ethnic neighborhoods. Q Street itself was once home to a large Greek population until riots in the early 20th century ran them out of the area. Eventually, Q Street became known as the Irish part of town and was often referred to as “Irish Hill.” However, while the residential areas of the Saint Mary’s neighborhood were predominately Irish, Q Street’s commercial district was integrated. This meant that different ethnicities and races often worked, ate, shopped, and drank together at these businesses.

At one time, South Omaha had 135 taverns. This, combined with the industrial environment, dense living conditions, and prejudiced stereotypes about immigrant communities led to the portrayal of Q Street as a “rough” part of town. Yet, in direct contradiction to these perceptions, the Saint Mary’s neighborhood thrived culturally and economically until the late 1960s and early 1970s, during which the Union Stockyards and packing plant industries began to decline due to the invention of hydraulic technology and refrigerated trucks. After officially closing in 1999, the site of the Union Stockyards was redeveloped as Metropolitan Community College and the South Branch Public Library. In 2018, new immigrant communities including Latino and refugee populations call the Saint Mary’s neighborhood home. Much like the past, South Omaha’s remaining packing plant jobs continue to attract groups willing to do laborious and dangerous work in order to provide for themselves and their families.

Image courtesy of Durham Museum.

This video is an interview with Tom Szczepaniak, done on July 19, 2019. It includes his memories of Parkvale Bakery, which his family owned, Q Street, and the Stockyards.

This video is an interview with Charles Leonard, done on July 22, 2019, during which he talks about Omaha’s Union Stockyards and Q Street.

Q Street Streetcar

-

This streetcar ran from 26th and Q to 30th and Fort.

The woman you see in this photo is Margaret Bell and this genuine smile on her face captures her sense of pride for the community. In 1945, the stockyards were at their peak and employees would take this streetcar to work every day. Many stockyard workers came from the 30th and Q Street area and were proud of the hard work that they did. This shared mentality influenced how tightly knit and integrated this community was. After work, they would take the streetcars home and have a drink at one of many local taverns or saloons; there were 135 in Omaha alone and more than a dozen in the Saint Mary’s neighborhood. By making the neighborhood accessible to thousands of people, the streetcars became the backbone of the area’s economy. However, without passionate drivers like Margaret Bell, none of this would have been possible.

Photo Courtesy of The Durham Museum Archives, Bostwick-Forhardt Collection.

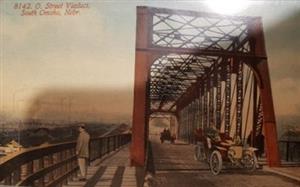

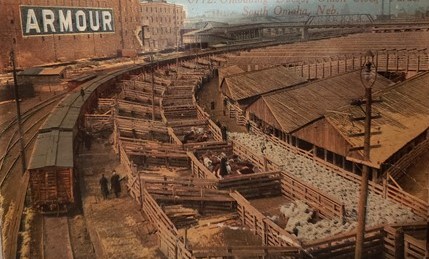

Q Street Bridge & Armour

-

This postcard shows the Q Street Bridge when it first opened. The Q Street Bridge was the lifeblood of South Omaha, because it was a way for truckers to deliver their cattle to the processing plant. Without it, I believe that South Omaha would never have become the number one packing plant in the nation. Furthermore, while this postcard shows the former Q Street Bridge that was used by South Omaha, in 2019 they are building a new one to serve the community.

The Armour plant was one of the four major meatpacking plants in South Omaha, along with Swift, Cudahy, and Wilson. The photo shown on the postcard depicts holding pens that would hold cattle or hogs. In this photo, there are sheep and cattle in the pens. The stockyard attracted workers from all over Omaha, including from both South and North Omaha who were looking for jobs. Not only did the stockyards bring jobs, but they also brought businesses. Q Street flourished with the opening of many businesses such as clothing, food, and community outreach centers. All and all, the stockyards greatly affected the neighborhood’s economy and culture.

2939 Q Street

-

Built in 1921, 2939 Q St. was part of a cluster of buildings that served the surrounding neighborhoods, as well as workers coming and going from the nearby stockyards and packinghouses. Initially, home to the Southside cigar store in 1921, subsequent tenants at the location included Geo Fries soft drink in 1932, and the Nicholas Knihal barber shop in 1933. In 1934, Stanley Zager opened a bar, one of many drinking establishments in the area that catered to the multitude of laborers pouring out of the stockyards and packinghouses each evening. In 1939, the space was briefly filled by a cigarette store before Zager opened a beverage shop in 1940. In the post-WWII era, the lot sat vacant until 1968, when the Greater Omaha Community Action took over the building. The GOCA, which was established as a part of the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, the centerpiece of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, helped people in poverty by giving young people jobs and activities to do during the summer. By 1977, though, as the stockyards went into steep decline, 2939 Q St. sat vacant. Because the stockyards were such a big part of the area’s economy, their decline caused many of the stores, restaurants, and bars on Q Street to close. In 2018, a small Mexican-American Church occupies the space and ministers to the growing Latino community in the area.

In 1968, a local anti-poverty agency called The Greater Omaha Community Action (GOCA) marked the opening of the new South Omaha office. Head of the South Branch, Regina Pflaum, and board members, Robert Murphy, Sam Harris, and Mary Miles started the GOCA program in the Saint Mary’s area. GOCA sent out advertising groups to South Omaha to publicize its war on poverty. Meetings were held at 2931 Q St. to nominate candidates for GOCA council positions and to discuss neighborhood conditions. Under its $313,000 program, GOCA employed 385 youths to give them activities and jobs over the summer. The GOCA board voted in May of 1968 to begin its own $801,510 neighborhood Youth Corps program. This committee was important to the neighborhood because it gave people jobs and got them involved in the community.

Photo Courtesy of the Omaha World-Herald.

3069 Q Street

-

The 3069 Q St. property started as a small house, but after burning down, a two-story building was erected and became the home of the Social Settlement of Omaha. This was a place for immigrant families to seek recreational and educational resources. Families had to have at least one family member employed at the stockyards to be qualified for these services. It was most popular from the 1920s to the late 1940s, when the stockyards reached their prime. Many South Omaha residents worked there. However, as crime increased in the area, the property became less and less of a safe haven because residents didn’t feel safe in the neighborhood. In 1964, the organization moved from 3069 Q St. to 4860 Q St. The original building that was once a hub for South Omaha families became vacant and was torn down in 1968. The Social Settlement Association-Omaha, which found its roots on Q Street, is now known as Kids Can Community Center in 2018 and offers full-day early childhood education and out-of-school programs.

Photo Courtesy of Durham Photo Archive.

In 2018, there’s a parking lot where the two-story building once stood. The lot has stood vacant since the original settlement house was demolished in 1968. This parking lot belongs to a Catholic charity called the Juan Diego Center. While it’s no longer a settlement house, it’s still serving the community as a charity.

2919 Q Street

-

2919 Q St. first appeared in The Omaha World-Herald in 1909 when a house fire destroyed it. According to the Douglas County Assessor, in 1920 this building was erected and it became a dry goods store owned by S. Vangrowick until 1925, when Moe Vann opened his own dry goods store. After Moe Vann went bankrupt around the 1930s, Sam Kaplan took over the dry goods store. In 1942, it became a Home Defense Girls Headquarters where they supported Black women and Black women’s work during World War II. It was affiliated with the NAACP and its goal was to bridge the physical separation between the North and South Omaha African American communities. Then in 1971, after the closure of the Armour packing plant, it became Carmona’s Mexican restaurant. It appears that the restaurant closed somewhere around the 1980s. When the packing plants closed, the decline on Q Street was slow, which was hard on the businesses and people already there. In 2019, it is an auto repair shop owned by SJ Mora LLC. In 2019, Q Street is a vibrant area with many businesses and within walking distance of the building. There are Mexican restaurants, delis, grocery stores, markets, and mechanics. There are also houses a few blocks away from the building called The South Side Terraces. Although it's not as industrial as it was when the Stockyards were open, it’s still a thriving area.

Now, the building is mostly made of tan-colored brick with some being covered up by siding and plaster at the middle and bottom levels. There are five frosted windows at the front of the building and on the top level there is a protruding brick in a V design.

A 2019 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"This program has made me realize the significance of history, and it has also made me realize that significant items should not be hidden away. It has changed me; I will not look at old buildings the same."

- Carly S.

"After attending this program, I know more about Omaha’s history and about what people went through in the past. I am also better at doing research and asking questions about history."- Julio C.

"I enjoyed making new friends and learning more about my community, South Omaha."- Briana R.

Youth-Driven Visions for the Future

-

Vision for the future included community involvement. Starting a grocery store with a farmer's market so people in the neighborhood could not only purchase healthy food, they would also be able to sell their own products. Along with the grocery store they wanted to add a café with a play place for children and an ice cream shop. The focus for the future was ultimately to bring the community together.

Resources

-

Associated Press. Cynthia Robinson of Sly and the Family Stone Dies at 71. The Hollywood Reporter, The Hollywood Reporter, 3 Dec. 2015.

Album covers and band pictures courtesy of Juan Lively and Ron Cooley.

“King Solomon's Mines Grand Opening.” Omaha Star, 22 Oct. 1970, p. 8.

Research combined by Carly S., Briana R, and Julio C. Students who worked on the project will attend high school at Central High School, Duchesne Academy, and South High School.