Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Dr. James Ramirez - Latino Educator

-

What were the major school reforms Dr. James Ramirez and others worked on to improve education for Latino/a students?

Jim Ramirez: Perseverance and Service

Dr. James "Jim" Ramirez

-

Dr. James Ramirez was born to Mexican immigrant parents in 1934 and raised in South Omaha. Consistent with the immigrant community of South Omaha, his parents worked in the meatpacking plants. After facing discrimination in school and being told that Latinos did not belong in college, he joined his father at Nebraska Beef. But Dr. Ramirez persevered, enrolled at Omaha University, and eventually earned his doctorate degree. He went on to dedicate his life to improving education and helping the community. Dr. Ramirez’s work has ensured more equality in education and opportunities for students in Omaha Public Schools.

While Dr. Ramirez was working at a meatpacking plant and attending night classes at Omaha University in the 1960s and 1970s, there were a variety of social movements trying to achieve equal rights. One example is the Chicano Movement. The Chicano Movement mostly took place in California and the American Southwest, but also across the country in places with Latino populations, including Omaha. One main focus of the Chicano Movement was education. High dropout rates of Mexican and Mexican American students indicated that students felt pushed out of schools. In order to address some of the problems that contributed to dropping out, Chicano activists and students wanted Mexican American history to be taught to give students knowledge of where they came from. They also wanted Mexican American teachers and administrators to inspire students to positions of leadership, access to bilingual classes and an end of corporal punishment for speaking Spanish in the classroom to encourage pride in their language and culture.

Immigration and migration to South Omaha, including Dr. Ramirez’s family story fits within national trends of immigration from foreign countries as well as internal migration from other states. Immigrants from many different countries came to South Omaha in search of work and to be with family. Mexicans and Mexican Americans mingled with European immigrants as well as African Americans moving from the South to the North as part of the Great Migration coming out of the World Wars. In South Omaha, all these groups converged on jobs available to them, especially the railroads and the meatpacking plants. As a result, the industry and neighborhoods of South Omaha developed as a multi-ethnic community.

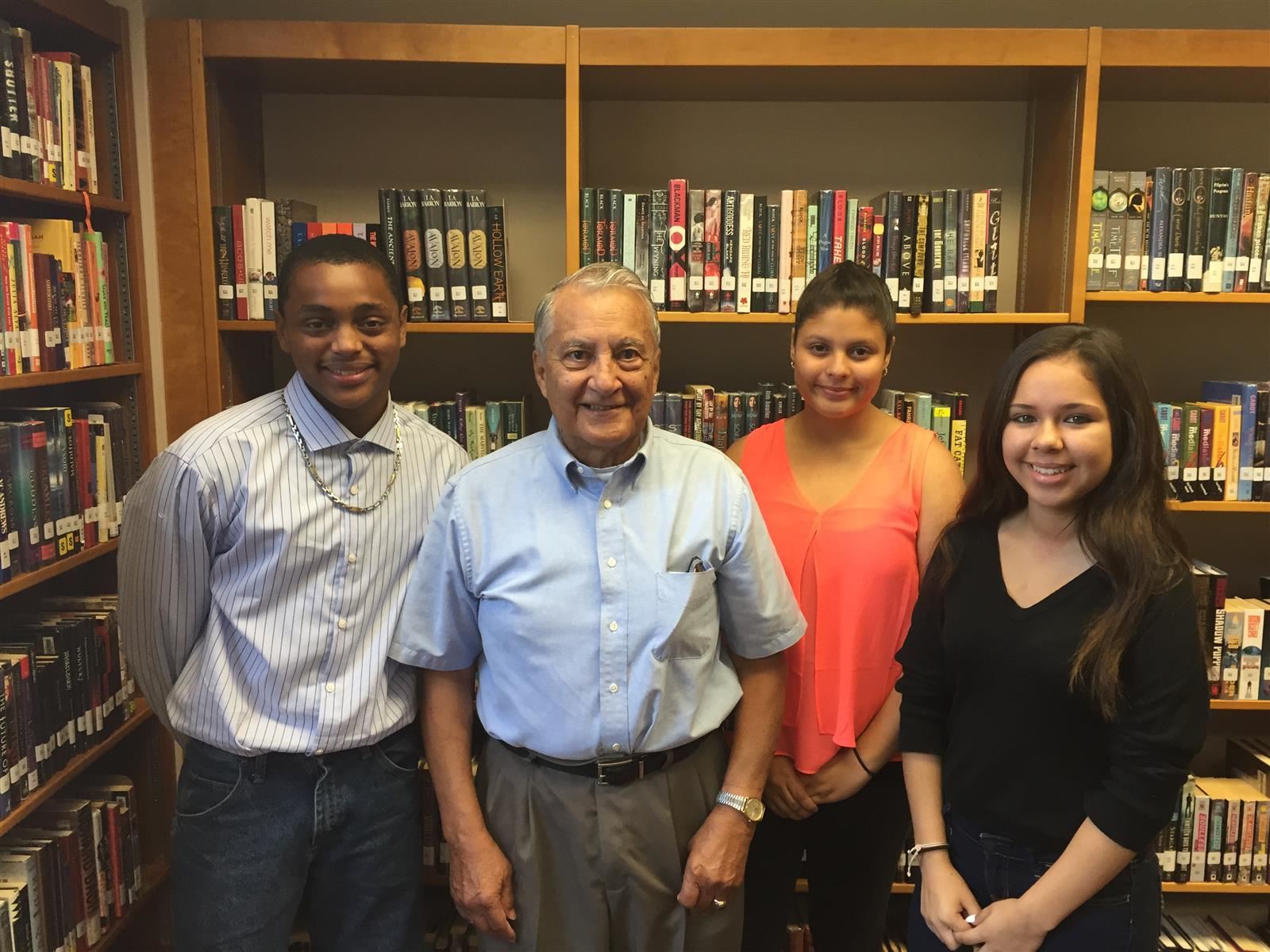

Video: 8 minute video interviewing Dr. James Ramirez and Ruben Cano, principal at South High School in 2015 and recruited from New Mexico by Dr. Ramirez to teach in Omaha.

South High

-

South High Magnet School, founded in 1901, is located at 4519 S. 24th St. in South Omaha. Dr. Ramirez graduated from South High in 1952. While attending South, Dr. Ramirez faced a lot of discrimination. Across the country, teachers and administrators would push Mexican American students into the working world instead of attending college. As a result of the advice he received from his counselor, Dr. Ramirez worked in a packing plant after high school. Despite these challenges, Dr. Ramirez went on to take night classes at college for 18 years to earn his bachelor’s degree, and he eventually earned his Ph.D. Dr. Ramirez did not like facing discrimination at South nor did he like being pushed out by the counselors. Because of his experiences, he decided to stay in Omaha and to help the community and improve education.

Although not personally involved or aligned with the Chicano Movement, Dr. Ramirez and activists of the Chicano Movement had parallel goals for improving the community and education. He thought that it would be better for the school to have more Mexican American teachers and bilingual education. He wanted more Mexican American teachers to work in schools throughout all of Omaha. He also wanted Mexican and Mexican American history taught in the classroom because he wanted people to know where they were from. Dr. Ramirez helped the community by improving education because students were allowed to look at the world differently; they made their parents and themselves proud, had more self-confidence as individuals, and pride in their community. Dr. Ramirez’s experience at South High School motivated him to make improvements in education. His success in creating programs to support minority students and recruit both Latino and African American teachers and administrators demonstrated how he lived out his philosophy, “never give up.”

Because of his high school experience at South, he was motivated to fight for these changes, and he made the community a better place by not giving up.

(Photo Courtesy of dataomaha.com)

Nebraska Beef

-

In the late 19th century through the 20th century, the stockyards and the meatpacking industry grew rapidly in Omaha. One of the plants was Nebraska Beef, where Dr. Ramirez, his father, and many other immigrants from their community worked. At the plant, workers performed the dangerous tasks of driving the animals, slaughtering them, butchering them, and packaging the meat.

The growth of the plants would not have been possible without industrialization and the growth of the railroads, which made transportation faster. The railroads were important to the meatpacking plants because they transported the meat; newly invented refrigerated rail cars were also vital for the packing industry because the meat had to be kept cold. Many immigrants came to the United States for jobs. In Omaha, the immigrants mainly worked at the meatpacking plants and the railroads.

After graduating from South High Magnet, Dr. Ramirez started working in the meatpacking plants with his father because counselors and teachers had told him college was not really for him, a common message to students of color. Working at Nebraska Beef, he realized he did not want to be working there his whole life like his father. He wanted to go to Omaha University (now known as UNO), but he was told people like him, meaning Mexican Americans, did not belong in college; therefore, he kept working at the packing plants. This experience is significant to Dr. Ramirez because if he had not worked at the meatpacking plants, he would not have realized how hard his father worked nor would he have been inspired to make something more out of himself. He kept working in the daytime and going to school in the nighttime. His experience being pushed out of schools and working in the meatpacking plants made him want to help others so they would have more options than he did.

(Photo By: Gabriel Gutiérrez 2015)

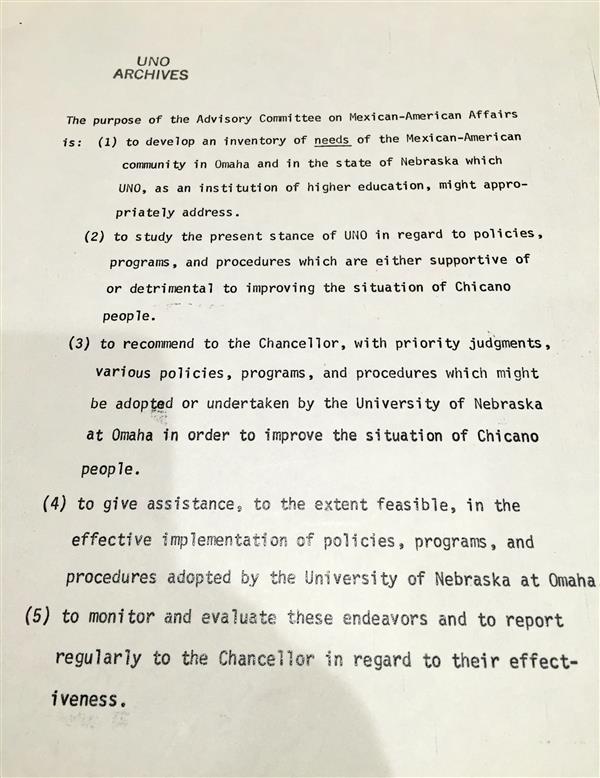

Committee on Mexican-American Affairs Document

-

This document is a statement of purpose produced by the Mexican American Advisory Committee, chaired by Dr. Ramirez, for the Chancellor of UNO in 1972. The Committee was formed to address problems common to minority students at the time, such as low enrollment rates, discriminatory advising, and a lack of minority representation in the faculty. The document was made to express the Mexican American Advisory Committee’s goals. The committee planned to list what the Mexican American community needed. Then, they created programs to help address those needs and make sure that the programs worked. By joining together with the University, Dr. Ramirez was able to achieve his goals of getting more minority teachers in the school and helping his community through the education of the students. This document shows that Dr. Ramirez was more about action instead of just talking. Dr. Ramirez thought education was important and that Mexican Americans were treated poorly and denied opportunities in schools. Dr. Ramirez changed the university by putting more Mexican American teachers and administrators in the school, which made the university friendlier to Mexican American students and gave them more opportunities in education.

(Photo: Statement of Purpose, Chancellor's Advisory Committee on Mexican-American Affairs. Courtesy of University of Nebraska Omaha Archives at the University of Nebraska at Omaha Criss Library)

Additional Information

-

The 1960s and 1970s witnessed an eruption of social movements from Civil Rights, Women’s Liberation, Free Speech, and Red Power to the Chicano Movement. Collectively, these movements strove for social equality and cultural recognition, relying predominantly on nonviolent tactics aimed to harness community and media attention. These movements were, furthermore, intended as revolutions of consciousness and sought to change self-perception while repairing group identity in the public eye while fighting for legislative protection of rights. In service of a revolution in thought, these movements included a focus on education, whether it was fighting for enforcement of desegregation, an elimination of sex discrimination in admissions policies, an end to vocational tracking of minority students, or emendations in textbooks that offered more complete histories of nonmainstream cultures or more honest accounts of imperial or racist encounters.

Challenging inequality in education for Mexican American students predated both the Chicano Movement and the landmark ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education (1954). In 1930, the plaintiffs in Salvatierra v. Independent School District argued not in pursuit of separate but equal (the then reigning doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) but for complete integration under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. While the court upheld the protection of the 14th Amendment, segregation was still allowed under the auspices of language deficiency, effectively allowing the continued segregation of students of Mexican descent. In 1931, efforts to “Americanize” Mexican American students in segregated classrooms were challenged in Alvarez v. Lemon Grove School District. Ninety-five percent of the students removed from the regular classrooms were American-born citizens, and even so, the judge pointed out the irony of attempting assimilation in isolation. The ruling stuck down segregation on the grounds that Mexican American students should be admitted to the classroom as members of the white race, but Native Americans and Asians could be rightfully segregated, therefore not addressing the racial issues of segregation. Lemon Grove served as a precursor to the more influential case Mendez v. Westminster in 1946. Arguing on the premise that education was a public right, Mexican American parents and students claimed that segregation in schools abridged their rights as citizens. The case struck down segregation and made the far-reaching argument that equality was not just a matter of matching textbooks or facilities but a matter of social equality in the educational experience.

Even after the 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, Mexican and Mexican American students continued to be subjected to racial discrimination, vocational tracking, punishment for speaking Spanish in the classroom, and courses that ignored or glossed over their place in the history of the United States. In addition, there was a dearth of Mexican or Mexican American teachers or administrators. The Chicano Movement took up these issues in the post-Brown era.

In Omaha, the multiethnic immigrant community of South Omaha, centered on available jobs on the railroad and in the meatpacking houses, faced many of the same issues in their schools. Dr. Ramirez’s story and goals parallel the fight taken up by the local manifestations of the Chicano Movement, although he was not an active participant. Both he and the movement argued that education was pivotal to the formation of a positive personal identity and the healthy growth of a community and that both were entitled to equality of access and experience in the classroom.

2015 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"At MIHV, I learned that a lot of history is invisible and that a lot of people don't know about it even when the history happened where you live. Even if that history happens to be where you live because I didn't know Dr. Ramirez and I lived in the same neighborhood and went to the same schools. One thing I learned from Dr. Ramirez is to "never give up."

— Jailene T.

"MIHV is a great experience! You get a high school credit and get to tell someone's story. The best part of the experience was getting to tell Dr. Ramirez's story. Many people have invisible histories and sharing it to others makes me happy."— Vanessa M-G.

"I'm a historian now and I was not until I started MIHV. I know how to research, tell someone's story, and find invisible histories. Something that inspired me from Dr. Ramirez's story was how he never quit and became a Doctor in Education. This inspired me to work in hard in life."— Jason K.

Resources

-

Advisory Committee to the Chancellor on Mexican-American Affairs. “Statement of Purpose.” University of Nebraska at Omaha, April 4, 1972. University of Nebraska at Omaha Archive.

Aliaga Linares, Lisette, 2014. A Demographic Portrait of the Mexican-Origin Population in Nebraska. Omaha, Nebraska: Office of Latino/Latin American Studies (OLLAS) at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

Bacon, David. Communities without Borders: Images and Voices from the World of Migration. Ithaca: ILR Press, 2006.

Biga, Leo Adam. “South Omaha’s Jim Ramirez: A Man of the People.” Leo Adam Biga’s Blog, August 1, 2010. https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/01/jim-ramirez-a-man-of-the-people/.

Bloom, Alexander, and Wini Breines. “Takin’ It to the Streets” : A Sixties Reader / Edited by Alexander Bloom, Wini Breines. 3rd ed.. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

“Chicano! History of the Mexican-American Civil Rights Movement.” PBS, 1996.

Foley, Neil. Mexicans in the Making of America, 2014.

Guglielmo, T. A. “Fighting for Caucasian Rights: Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and the Transnational Struggle for Civil Rights in World War II Texas.” Journal of American History - Bloomington 92, no. 4 (2006): 1212–37.

Gouveia, Lourdes, Christian Espinosa and Yuriko Doku. 2012. Demographic Characteristics of the Latino Population in the Omaha-Council Bluffs Metropolitan Area. April. Omaha, NE: Office of Latino/Latin American Studies (OLLAS), University of Nebraska at Omaha.

Nebraska State Historical Society, and Mead & Hunt (Firm). Reconnaissance Survey of Portions of South Omaha: Nebraska Historic Buildings Survey. Mead & Hunt, 2005.

Research compiled by: Jason K., Vanessa M-G., Jailene T.