Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

African Americans in the Civil War

-

What were the experiences of African Americans during the Civil War, and how were they treated after the conflict?

Remembering the Events from the American Civil War

-

“Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship” –Frederick Douglass.

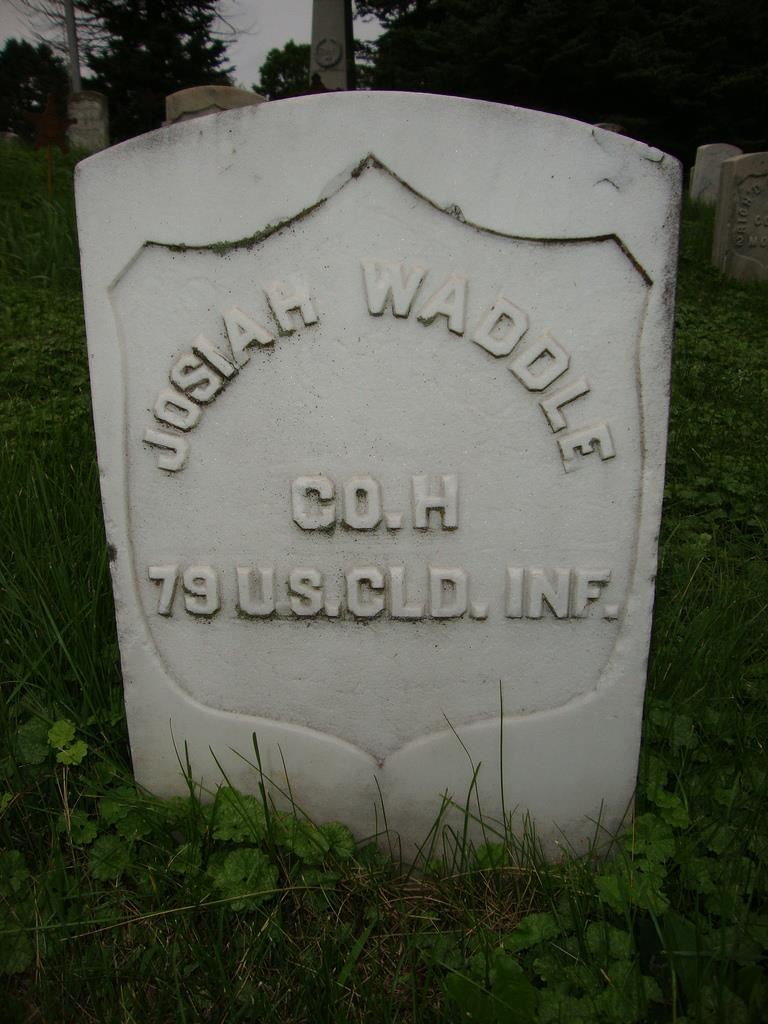

“Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship” –Frederick Douglass.Josiah's tomb is located in the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Circle at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Omaha, Nebraska. He was the second to last remaining African-American Civil War veteran in Omaha at the time of his death.

American Civil War

-

During the years of the Civil War thousands of African Americans played a crucial role in defending our freedoms. As the guns fell silent across the nation, these newly minted veterans saw new lives in the North. Hundreds of veterans and their families established themselves in Omaha. Among those who made Omaha home were three men: Edward Jones, Josiah Waddle and July Miles. We learned about the roles they played in one of the pivotal conflicts in our history.

A 9:25 video produced in 2011 interviewing Creola Woodall and her work uncovering the 58 African Americans buried in Row 19 at Laurel Hill Cemetery, many in unmarked, shallow graves.

African-American Soldiers In The Civil War

-

African Americans played a vital role during the Civil War. Without African American soldiers, the outcome of the war might have been very different. While free to serve, African American soldiers faced racism and segregation during the war. African Americans were involved in every major campaign during the last years of the conflict except General William Sherman's infamous march to the sea. Racial tensions relegated many African American soldiers to labor-intensive duties, such as trench digging and the building of fortifications. It was thought that African Americans developed immunity to malaria and were thus used in swamp warfare where white soldiers would become sick. Blacks in the war were paid $10 a month and $3.50 for clothing. African Americans made up 10 percent of all Union soldiers, but casualty rates left one in three soldiers dead.

This is a New York Militia uniform. Unfortunately, it was neither worn by an African American nor in battle. Yet this period artifact shares many characteristics of the uniforms worn by all Civil War soldiers, including African American troops. The uniform was worn by Samuel B. Hall of the 7th Regiment in 1863. The jacket is of rough wool with a lining on the inside for comfort. The belt is white with a brass belt buckle (the image on the buckle is an eagle, possibly the symbol of the Union or the NYM). The hat is a typical Civil War era campaign cap. A wooden cartridge box, covered in leather and adorned with a brass eagle, would sit at the waist for quick access. (Uniform Courtesy of Douglas County Historical Society)

Josiah Waddle, 83

-

Josiah Waddle was born Aug. 7, 1849, in Springfield, Missouri, to enslaved parents. As a slave, Josiah took his master's last name, Waddle. When the Civil War erupted across the country Josiah was only 12 years old. Although he was so young, he wanted to participate in the war. He spent almost all his spare time learning the blacksmith and mechanical trade so he could be of some use to the war effort. In 1863, he tried to enlist in the U.S. Army, even though he was only 14. Because he was young, he wasn't allowed to enlist but was given the job of taking care of a captain's horses. Waddle became well-known in the camp and he followed them to Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. After being abandoned by the camp, he went to Ft. Scott, Kansas, where he was accepted into service due to his size. He served two years and seven months before his honorable discharge on Oct. 9, 1863. Waddle stayed in Ft. Scott for several months before moving to Topeka, Kansas to be with his family. After visiting his sister in Nebraska City, Nebraska, he learned the barber trade and moved to Omaha. He was the first African American barber in Nebraska. After opening a barbershop, he also became very interested in music. Waddle later set up a 15-piece African American band and orchestra in Omaha called “Waddle’s Ladies.” Waddle is an important figure among Nebraska Civil War veterans and an early leader in the African American music community in Omaha. (Photo Courtesy of Douglas County Historical Society)

Josiah Waddle was born Aug. 7, 1849, in Springfield, Missouri, to enslaved parents. As a slave, Josiah took his master's last name, Waddle. When the Civil War erupted across the country Josiah was only 12 years old. Although he was so young, he wanted to participate in the war. He spent almost all his spare time learning the blacksmith and mechanical trade so he could be of some use to the war effort. In 1863, he tried to enlist in the U.S. Army, even though he was only 14. Because he was young, he wasn't allowed to enlist but was given the job of taking care of a captain's horses. Waddle became well-known in the camp and he followed them to Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. After being abandoned by the camp, he went to Ft. Scott, Kansas, where he was accepted into service due to his size. He served two years and seven months before his honorable discharge on Oct. 9, 1863. Waddle stayed in Ft. Scott for several months before moving to Topeka, Kansas to be with his family. After visiting his sister in Nebraska City, Nebraska, he learned the barber trade and moved to Omaha. He was the first African American barber in Nebraska. After opening a barbershop, he also became very interested in music. Waddle later set up a 15-piece African American band and orchestra in Omaha called “Waddle’s Ladies.” Waddle is an important figure among Nebraska Civil War veterans and an early leader in the African American music community in Omaha. (Photo Courtesy of Douglas County Historical Society)

Veterans Arrive In Omaha: The Great Migration

-

At the turn of the 20th century, African Americans in the South began to look for a better life in the North. From the 1910s until the 1970s, about 7 million men, women, and children moved across the country. In the South, Jim Crow laws restricted the political rights of African Americans and forced them back into farming and sharecropping. Natural disasters and the agricultural decline also "pushed" them away from the South. The North had a lot to offer to Blacks: industrial jobs, better education and increased freedoms. Many migrating African Americans traveled by train with only a small number of possessions to start a new life. Many of those who came to Omaha initially settled in South Omaha because of the jobs at the meatpacking plants. Later, many African Americans moved into the Near North Side (what is now known as North Omaha) because they learned they could own their own businesses. But these new lives were not always full of milk and honey. There was substandard housing and a lack of jobs for African Americans. Also prevalent in Omaha was the real estate practice of redlining. Redlining was when you weren't allowed to own houses past a certain area of the city based on your race. This prevented African Americans from moving out of the Near North Side and thus established the predominately African American neighborhood it remains today. (Public Domain Photo)

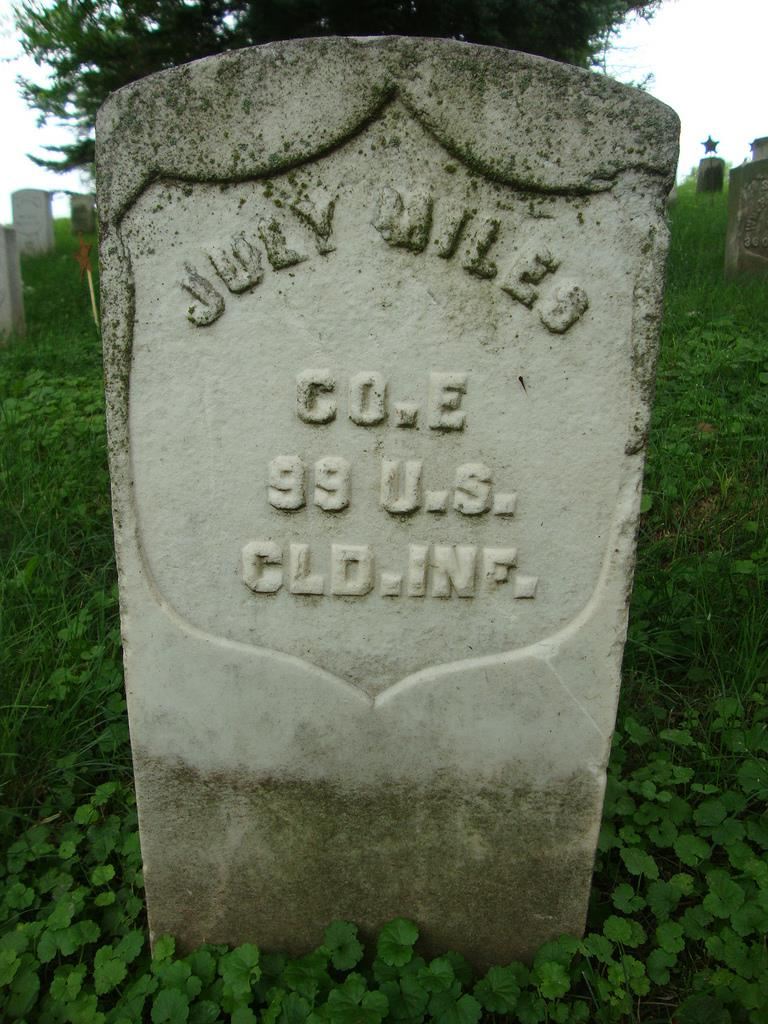

July Miles' Tomb

-

S. “July” Miles was born in approximately 1848 near Montgomery, Alabama. He was a slave and ran away to join the Union during the Civil War. Once across Union lines, he enlisted in the 96th Colored Infantry. Miles joined at the age of 16. During most of his service, Miles was on a gunboat in the Gulf of Mexico doing engineering duties and fieldwork. After the war, he made his home in Mobile, Alabama. Miles got a job working on various steamboats working their way up and down the Mississippi River. His brother then located him a job with the Union Pacific Railroad, working on private cars and traveling around the country. Miles was then transferred to the Pullman Division and stationed in Omaha. For five years, he worked on the private car of fellow Civil War veteran, General Grenville M. Dodge. He taught himself to read and write and reading became one of his pastimes. Miles was one of the oldest congregants of the Mount Moriah Baptist Church located on North 24th St. and Ohio St. in 2011. He had five wives during his life. At the time of his death, Miles had one daughter living with him, from his fourth wife. Miles lived in Omaha from 1892 until his death in 1941. He was the last African American Civil War veteran in Omaha at the time of his death.

S. “July” Miles was born in approximately 1848 near Montgomery, Alabama. He was a slave and ran away to join the Union during the Civil War. Once across Union lines, he enlisted in the 96th Colored Infantry. Miles joined at the age of 16. During most of his service, Miles was on a gunboat in the Gulf of Mexico doing engineering duties and fieldwork. After the war, he made his home in Mobile, Alabama. Miles got a job working on various steamboats working their way up and down the Mississippi River. His brother then located him a job with the Union Pacific Railroad, working on private cars and traveling around the country. Miles was then transferred to the Pullman Division and stationed in Omaha. For five years, he worked on the private car of fellow Civil War veteran, General Grenville M. Dodge. He taught himself to read and write and reading became one of his pastimes. Miles was one of the oldest congregants of the Mount Moriah Baptist Church located on North 24th St. and Ohio St. in 2011. He had five wives during his life. At the time of his death, Miles had one daughter living with him, from his fourth wife. Miles lived in Omaha from 1892 until his death in 1941. He was the last African American Civil War veteran in Omaha at the time of his death.

Edward Jones

-

Private Edward Jones was born a slave in March of 1844 in Clark County, Kentucky. Slave ledgers reveal he was owned by a man named James Steward. Private Jones enlisted on May 30, 1865, in Maysville, Kentucky. In Jones' Muster Rolls, he was described as 5' 8" and 18 years old. He listed his occupation at the time of his enlistment as a "laborer". He was assigned to the United States 13th Colored Heavy Artillery (USCHA). Private Jones was mustered out on Nov. 18, 1865, in Louisville Kentucky. The 1880 Census Records show Jones living in Columbus, Nebraska. By the 1890 Census, Jones was living in South Omaha. In 1894, he married his second wife, Sarah Jones. He owned a home, with a mortgage, at what is now 4409 S. 27th St. Jones was considered to be a pillar of the community. He was active with the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) in Omaha. He was even elected to an officer position with the GAR. He attended the First Christian Church. Jones and his family owned several homes along 27th Street in South Omaha. Edward Jones died at his home at the age of 57 after an illness that lasted seven months. According to his obituary in the Omaha Daily Bee newspaper, Jones was one of the best known African Americans in South Omaha. The Bee also reported that he left behind "considerable property" and that he was survived by his wife and six children.

Private Edward Jones was born a slave in March of 1844 in Clark County, Kentucky. Slave ledgers reveal he was owned by a man named James Steward. Private Jones enlisted on May 30, 1865, in Maysville, Kentucky. In Jones' Muster Rolls, he was described as 5' 8" and 18 years old. He listed his occupation at the time of his enlistment as a "laborer". He was assigned to the United States 13th Colored Heavy Artillery (USCHA). Private Jones was mustered out on Nov. 18, 1865, in Louisville Kentucky. The 1880 Census Records show Jones living in Columbus, Nebraska. By the 1890 Census, Jones was living in South Omaha. In 1894, he married his second wife, Sarah Jones. He owned a home, with a mortgage, at what is now 4409 S. 27th St. Jones was considered to be a pillar of the community. He was active with the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) in Omaha. He was even elected to an officer position with the GAR. He attended the First Christian Church. Jones and his family owned several homes along 27th Street in South Omaha. Edward Jones died at his home at the age of 57 after an illness that lasted seven months. According to his obituary in the Omaha Daily Bee newspaper, Jones was one of the best known African Americans in South Omaha. The Bee also reported that he left behind "considerable property" and that he was survived by his wife and six children.Edward Jones was buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery. It was the discovery of Jones’s grave by volunteer caretaker Creola Woodall that started the process of recognizing all of the Civil War veterans and African Americans buried at Laurel Hill. Woodall spent years researching the forgotten story of Edward Jones. This photo of Edward Jones's grave was taken shortly after being rediscovered. (Research Courtesy of Creola Woodall)

Laurel Hill Row 19

-

Laurel Hill is a small cemetery in South Omaha, off the Kennedy Freeway. Row 19 is at the back of the cemetery in an area that was not well taken care of. Trees, bushes and other plants covered the area. A volunteer caretaker was the one who initially stumbled upon the graves, spotting the tombstone of Edward Jones beneath the brush. Boy Scouts and other community members worked together to clear away the debris and plants covering Row 19. During the clearing process, human bones that worked their way up to the surface indicated that these were shallow burials. The absence of other headstones, shallow burials, and forgotten internments led volunteers to interpret the site as a “Potter’s Hill” or location for the graves of the economically and socially marginalized. Fifty-eight African Americans are buried in Row 19. Some were soldiers from the Civil War, such as Edward Jones and James Adams. Others were free African Americans who lived in Omaha. Most of the graves were unmarked. A memorial was placed on the row to honor all of the African Americans laid to rest there. (Photo Courtesy of Creola Woodall)

Laurel Hill is a small cemetery in South Omaha, off the Kennedy Freeway. Row 19 is at the back of the cemetery in an area that was not well taken care of. Trees, bushes and other plants covered the area. A volunteer caretaker was the one who initially stumbled upon the graves, spotting the tombstone of Edward Jones beneath the brush. Boy Scouts and other community members worked together to clear away the debris and plants covering Row 19. During the clearing process, human bones that worked their way up to the surface indicated that these were shallow burials. The absence of other headstones, shallow burials, and forgotten internments led volunteers to interpret the site as a “Potter’s Hill” or location for the graves of the economically and socially marginalized. Fifty-eight African Americans are buried in Row 19. Some were soldiers from the Civil War, such as Edward Jones and James Adams. Others were free African Americans who lived in Omaha. Most of the graves were unmarked. A memorial was placed on the row to honor all of the African Americans laid to rest there. (Photo Courtesy of Creola Woodall)

Black Soldiers Memorial

-

After discovering the graves in the back of Laurel Hill cemetery, Creola Woodall and other community members hoped to place a memorial marker on Row 19. Shortly after their discovery, the Veterans of Foreign Wars placed wooden crosses at the site, but they were constantly moved because of mowing and began to rot. People thought a permanent memorial would be much better than the old crosses. Woodall conferred with others from the community to come up with the text that would be written on the memorial. On July 3, 2011, a ceremony was held to dedicate the memorial to the African Americans buried in Row 19.

Additional Information

-

Following the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, the Bureau of Colored Troops was established. A total of 166 colored regiments, consisting of approximately 200,000 men, were formed between 1863 and 1865. Many of the African American enlisted men were free Blacks from the North, but numbers increased as recently freed slaves enlisted to free those remaining in bondage. Although these units consisted of only African American enlisted men, their officers were nearly always white. The most famous of these units was the 54th Massachusetts, whose story was told in the award-winning film, Glory.

The racial tensions at home settled into military life. Private Richard of the 11th Colored Heavy Artillery was told by a white solder that “before he would stand by the side of a Black man and fight, he would be shot in the back.” The massacre of African American prisoners of war at Fort Pillow by Confederate soldiers is an infamous example of the Rebel treatment of Black Union troops. Black soldiers also received less pay than their white counterparts. Yet these men persevered against widespread racism and the struggle of war to abolish the institution of slavery. Overall, 16 African American soldiers earned the Congressional Medal of Honor for courageous action in combat during the war. Military participation during the Civil War was a transformative experience for African Americans, as it was again during the conflicts of the 20th century, as soldiers actively fought for the freedoms they did not necessarily have at home. Veterans returned empowered with their consciousness raised.

African Americans began migrating to the North shortly after the Civil War concluded, but the massive numbers seen during “The Great Migration” did not begin until the early 20th century. Numerous Civil War veterans, July Miles, Edward Jones, and Josiah Waddle among them, moved to Omaha as a result of The Great Migration. Miles arrived in Omaha in 1892. After years as an employee of the Union Pacific, he decided to settle in Omaha and transferred to the Pullman Division of the railroad. At the time of death on June 12, 1941, he was the last remaining African American Civil War veteran and the oldest ex-Union Pacific employee in Omaha.

Veterans’ organizations, notably the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), fostered community organization and continued the memory of the war. July Miles and Josiah Waddles were the last African American members of Omaha’s Old Guard Post No. 7, which was a consolidation of all previous posts in the city after membership dropped. Remnants of the GAR remain. The GAR Circle in Forest Lawn cemetery was donated to the group in 1899 and contains the remains of dozens of local veterans, including many African American soldiers, such as Josiah Waddle and July Miles. It is one of the few, if only, integrated GAR burial sites in the country.

A 2011 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"When I first walked into camp I honestly didn’t believe I’d relate to this project at all. Yet by doing this research I’ve discovered how much the African-American community has affected me. From things as simple as food or music it has influenced aspects of my life. This camp has changed me in so many ways and most likely changed me in ways I don’t even know about yet."

- Brandon H.

"It was really cool to find out about the different cultures in North Omaha. It really surprised me to discover the histories of other cultures like the Eastern European and Jewish immigrants who moved to Omaha. It was really cool to do research on someone whose history was lost for so long. I couldn't imagine being buried without anyone knowing where I was. The knowledge I learned here will follow me for the rest of my life."

- Malik W.

"This camp was a great experience and gives us a one-up on the rest of our peers when we go back to school. I will be able to walk away with a vast amount of knowledge and I didn’t learn it from a textbook or from taking notes but was given hands-on opportunities to learn. I don’t know why anyone would turn down the chance to be in this camp."

- Tessa H.

Resources

-

Ira Berlin, Joseph P. Reidy, and Lesile S. Rowland. Freedom’s Soldiers: The Black Military Experience in the Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hondon B. Hargrove. Black Union Soldiers in the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 1988.

Ashley M. Howard. Then the Burning Began: Omaha, Riots, and the Growth of Black Radicalism, 1966-1969. Master’s Thesis. University of Nebraska at Omaha, 2006.

John Melinagio. “Bugle Still Sounds for Civil War Veterans.” Omaha World-Herald. May 29, 1989.

July Miles. WPA Interview, 1938. American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writer’s Project, 1936-1940. memory.loc.gov

Edwin S. Redkey, editor. A Grand Army of Black Men: Letters from African-American Soldiers in the Union Army, 1861-1865. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Research compiled by: Malik W., Tessa H., Brandon H.