Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson - African American Education

-

What were the various methods Dorothy Eure and Lerlean Johnson used to advance equality and empowerment?

Fighting for Equality: Women Take a Stand

Dorothy Eure and Lerlean Johnson

-

In the 1960s, African Americans in Omaha experienced racial discrimination in the areas of education, housing, and entertainment. Dorothy Eure was upset with the treatment of African Americans, so she took it upon herself to make a change. Her political activism started at an early age. In high school she created a group called Tomorrows World, which focused on getting African American teachers into Omaha Public Schools. Throughout the 1960s, she continued her activism in Omaha participating in picketing and other demonstrations for equal housing and education. In 1963, she traveled to Washington D.C. to be part of the historic March on Washington.

In 1973, Dorothy Eure joined forces with Lerlean Johnson to integrate Omaha Public Schools. The city was racially segregated and African Americans were restricted to only living in North and South Omaha. Schools in racially segregated areas did not provide the same educational opportunities as white, suburban schools. Together they led the way to desegregate Omaha Public Schools through mandatory busing, which allowed African Americans to attend schools outside their restricted area.

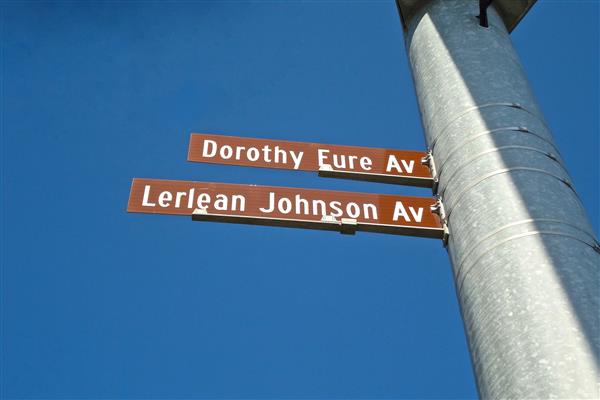

Eure and Johnson have been memorialized on a street sign due to their activism for equal education. Activists today credit Eure and Johnson for pioneering the way for educational change.

Fair Housing

-

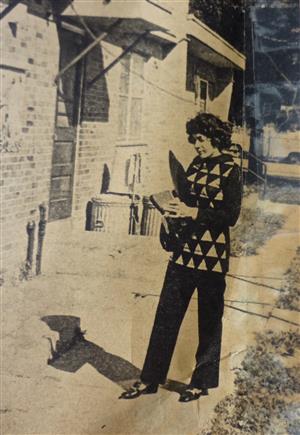

During the 1960s, the country experienced racial segregation in housing and African Americans could only live in certain areas of town. In Omaha, North Omaha was the designated area for African Americans. For example, Bob Boozer was a well-known African American professional basketball player who wanted to live outside of the restricted area of North Omaha. Even though he was famous and wealthy, he was denied housing outside the area because of segregation. Dorothy Eure felt that housing segregation was wrong; she believed that anyone should live where they pleased as long as they could afford it. As a result, she took a leading role in the local open housing campaign. On Oct. 30, 1963, Eure led a demonstration for equal housing at the old City Hall building. Many people took off from work and kids didn’t go to school, so that they could protest the restricted housing. The amount of support that day was so overwhelming and Eure said, “I’ll always remember that day; it was very historic.” During that moment, Eure felt hopeful that a change in housing was near. Eure never gave up the fight for equal housing. In 1969, the open-housing ordinance was finally adopted, which meant African Americans were no longer restricted to North Omaha. (Photo courtesy of Darryl Eure)

During the 1960s, the country experienced racial segregation in housing and African Americans could only live in certain areas of town. In Omaha, North Omaha was the designated area for African Americans. For example, Bob Boozer was a well-known African American professional basketball player who wanted to live outside of the restricted area of North Omaha. Even though he was famous and wealthy, he was denied housing outside the area because of segregation. Dorothy Eure felt that housing segregation was wrong; she believed that anyone should live where they pleased as long as they could afford it. As a result, she took a leading role in the local open housing campaign. On Oct. 30, 1963, Eure led a demonstration for equal housing at the old City Hall building. Many people took off from work and kids didn’t go to school, so that they could protest the restricted housing. The amount of support that day was so overwhelming and Eure said, “I’ll always remember that day; it was very historic.” During that moment, Eure felt hopeful that a change in housing was near. Eure never gave up the fight for equal housing. In 1969, the open-housing ordinance was finally adopted, which meant African Americans were no longer restricted to North Omaha. (Photo courtesy of Darryl Eure)

Afro-Academy of Dramatic Arts

-

Dorothy Eure’s activism played a role in her children’s lives. Two of her sons, Harry and Darryl, started the Afro-Academy of Dramatic Arts in 1969. In the mist of racial discrimination, the country experienced a rise in the Black Power movement. The movement emphasized Black pride and culture. The Afro-Academy of Dramatic Arts gave African Americans the ability to express themselves through the arts. It was the first Black theater in Nebraska. Darryl and Harry started performing at the Omaha Show Wagon. They loved to tap dance, sing, act, and perform. Eure and her two sons wanted something more. They wanted a place where African Americans could be free to express and build their identity and culture. They performed plays like “Rose Red” and “A Raisin in the Sun,” which highlighted racial issues.

The Afro-Academy of Dramatic Arts first started in their garage and then moved into an old gambling place with a small stage. They tried charging money for the plays; however, due to segregation and inequality in education and jobs, many did not have the money to pay. The Eures allowed those without money to enjoy the shows anyway. They knew it was important for African Americans to experience the arts and increase pride. As their performances grew, they needed more space, so they got permission to perform in a church located on 30th and Izard (shown in picture). They gave lessons to African Americans of all ages on performing, acting, creative writing, and music. They wanted African Americans, especially children, to have an opportunity to express themselves and their culture.

(Photo courtesy of Google Earth)

Integration of Omaha Public Schools

-

To memorialize Dorothy Eure and Lerlean Johnson’s work, the Omaha City Council approved naming a street sign in their honor. Dorothy Eure Avenue and Lerlean Johnson Avenue are found on the corner of 30th and Cuming streets. The signs hang next to the administrative offices of Omaha Public Schools where Eure and Johnson fought so hard for integration.

In the 1960s, African Americans throughout the country suffered from racial inequality and segregation in education. In Omaha, African Americans were limited to the schools located in their segregated neighborhood of North Omaha. The few schools they did have were old, run down, and broken. Lerlean Johnson and Dorothy Eure thought that had to change. They valued education as an equalizer, and knew education could provide more opportunities. They protested against the inequality and then took legal action. In 1973, Eure, Johnson, and five other women brought a lawsuit against Omaha Public Schools. They argued that children should be able to go to any school regardless of color. They fought for busing and integration. The women’s fight continued for three years until they finally won the lawsuit.

When busing began, white kids started going to predominantly African American schools, and African Americans started attending predominantly white schools. This caused the schools in North Omaha to make improvements to their buildings that had been run down and dilapidated. African American students experienced newer and better resources, classes, and equipment. Because of Eure, Johnson, and the five other women’s work with the public schools, there was more diversity in the classrooms, and some schools in North Omaha began specialized programs in math, technology, and science. Despite their achievement, not everything was solved. The struggle for equal educational opportunities still persists today.

Additional Information

-

Omaha has a long, notorious history of racial segregation. While segregated education legally ended in 1954 and the civil rights movement had begun to subside on the national stage by 1970, African Americans in Omaha continued to face de facto discrimination in housing, employment, education, and social spheres. Dorothy Eure and Lerlean Johnson, both African American women, dedicated their lives to combatting inequality as well as celebrating their cultural heritage. Eure and Johnson were two of seven women to sue the Omaha Public School District in 1973, which led to limited busing, an attempt to increase integration in the district, in 1976. The busing program ended in 1999 despite testimony from numerous African Americans that it had increased academic achievement and improved race relations in Omaha.

Both Eure and Johnson also worked at the Legal Aid Society of Nebraska, fighting on behalf of the underprivileged for suitable housing and Social Security benefits. Eure served a critical role in organizing demonstrations at City Hall against redlining. Eure, along with her sons, also founded the Afro Academy of Dramatic Arts, which offered African Americans an outlet for participating in the arts as well as entertainment for residents of North Omaha.

The students who studied Eure and Johnson had the privilege of interviewing their sons, both of whom are immensely proud of their mothers’ work. Ironically, the portion of 30th Street chosen to honor Eure and Johnson runs directly in front of the OPS administration building, the very entity that was their adversary for so long; this was not a point of contention in Lerlean Johnson’s eyes at the time of the street’s dedication, however.

Although the city of Omaha has not yet conquered the issue of segregation in many areas, these women had the courage to take crucial steps toward the pursuit of equality that continues to this day. Dorothy Eure and Lerlean Johnson had a profound impact on their city, despite the additional challenges they faced in the political sphere as both minorities and women. They serve as excellent examples of political activists dedicated to the empowerment of the African American community in Omaha.

2015 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"My best experience here has been making new friends, learning new things about Omaha's history, having fun, and working with my group. "

-Ty'Asia B.

"I've learned many things during the summer program. One thing I learned about was interviewing people and learning about the histories behind Omaha. Now when I go down a road and see a street sign, I won't think its just a simple street sign; it could be a street sign with history behind it."-Eh Ree T.

"I have learned that many things started in Omaha and many things happened in Omaha. The history is more exciting than I thought, and I appreciate Omaha's history more. It was a cool experience to actually get to interview the people who experienced the history."-Shane M.

Resources

-

Baker, Jodi. "Omaha Street Renamed After Civil Rights Pioneers." WOWT.com. 03 Aug. 2009. Web 15 July 2015.

Eure, Darryl. Application for Commemorative Name. 09 Apr. 2009. Planning Department, Omaha, Nebraska.

"Interview with Darryl Eure." Personal Interview. 21 July 2015.

"Interview with A'Jamal Rashad Byndon." Personal Interview. 20 July 2015.

Smith, Alonzo N. Black Nebraskans: Interviews from the Nebraska Black Oral History Project II. Nebraska Committee for the Humanities, 1982.

United States of America v. The School District of Omaha, State of Nebraksa. LexisNexis. United States District Court for the District of Nebraska. 15 Oct. 1974. Print.

Research compiled by: Shane M., Eh Ree T., and Ty'Asia B.