Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Black Elk: Preserving a Culture

-

In the late 1800s, many Native American communities lost their homes and traditions due to the expansion of the United States into the Great Plains. One of these communities was the Lakota Sioux. During the Plains Indian Wars, the United States government had outlawed Native American spirituality and the buffalo were almost completely wiped out by the government and white American settlers. These things threatened to destroy the Lakota traditions that were built on the use of the buffalo for food and cultural practices.

In the late 1800s, many Native American communities lost their homes and traditions due to the expansion of the United States into the Great Plains. One of these communities was the Lakota Sioux. During the Plains Indian Wars, the United States government had outlawed Native American spirituality and the buffalo were almost completely wiped out by the government and white American settlers. These things threatened to destroy the Lakota traditions that were built on the use of the buffalo for food and cultural practices.After being put on reservations such as Pine Ridge in South Dakota, the Lakota people continued to struggle to keep each other and their traditions alive. Conditions on the reservations were often poor, which led to issues within the tribe. Black Elk was forced to live in these conditions as well, but remembered what Lakota life was like before, as well as the events that led to the destruction of that life. In 1930, the poet and author John G. Neihardt met Black Elk and gave him the opportunity to share his memories and raise awareness of Lakota culture and traditions.

In 1932, Neihardt published his book on Black Elk, titled Black Elk Speaks, which has helped preserve the way of life the Lakota had almost lost in the early 1900s. Because he had been a Medicine Man, Black Elk had a deep understanding of Lakota spirituality. His book has helped to spread this understanding to Native and non-Native communities within the United States, helping to bridge the gap between these two cultures by highlighting what connects us all as people.

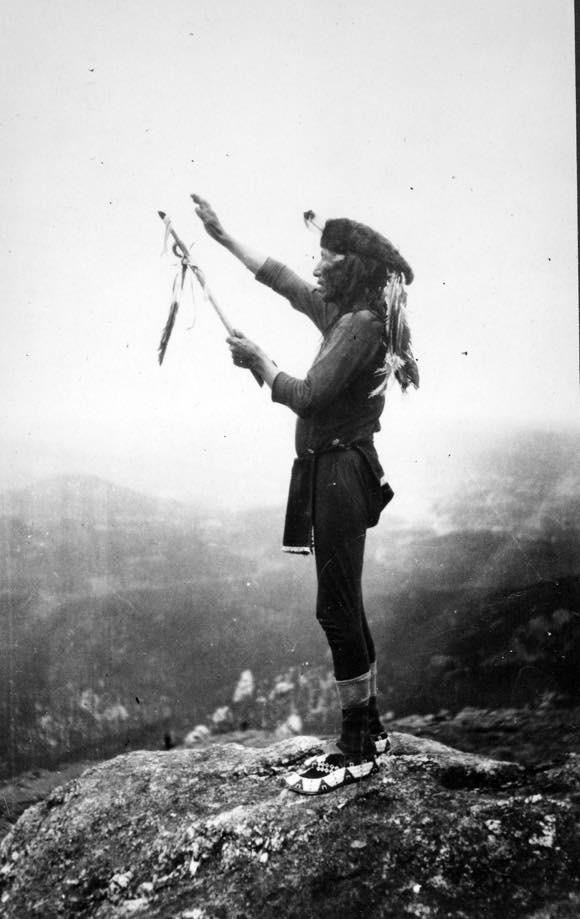

Image: After his interviews with John G. Neihardt, Black Elk spoke to the Six Grandfathers from Harney Peak

Published on July 22, 2016

Students interviewed Amy Kucera, director of the Niehardt Center, and Sheila Rocha PhD, a member of the Lakota tribe.

Black Elk's Early Life

-

The Lakota are a tribe of the Great Plains region who once lived in tipis and traveled with the buffalo. Growing up in this environment, Black Elk learned the Lakota's traditional ways. They used the buffalo for all their needs, and celebrated the animal after it was killed in a ceremony. The tribe acted as a large family and shared everything.

According to the Lakota Winter Count, Black Elk was born in the “Winter When Four Crows Were Killed” (around 1863) in December, or “Moon of the Popping Trees,” on the banks of the Little Powder River. He was the fourth Black Elk, the first was his great-grandfather. As a young boy, Black Elk played many games, but in the games of battle, or “Throwing Them Off Their Horses,” he hoped that someday he would be in a real battle against the wasichus, or white man, and drive them from their people’s land.

At nine years old, Black Elk had a great vision while he was in a coma. The vision revealed two messengers for the Six Grandfathers. The messengers came to earth and brought Black Elk into the sky, where he saw horses that represented the four directions (North, South, East, and West). He was led to the Rainbow Tipi, where the Six Grandfathers were waiting for him. The Six Grandfathers represented the four directions, as well as the Earth and the Sky. Each one gave him gifts, then sent him back to his family. Black Elk felt much better when he woke up, and knew that he was destined to be Medicine Man.

In Lakota culture, a Medicine Man is a holy person who can speak for the Great Spirit and heal the sick. All of Black Elk’s uncles and his father were Medicine Men, and Black Elk took up the role as well when he was 19. He healed many people, including the son of Cuts-to-Pieces. He prayed and sang over the boy, and the next day the boy was healthy again.

Black Elk’s early life allowed him to learn the traditional way of life and the values of the Lakota, which he carried with him for the rest of his life.

Period of Transition

-

During Black Elk’s life, the United States government wanted a lot of the land that belonged to the Lakota. Black Elk witnessed several battles between the United States and the Lakota tribe, including the Battle of the Greasy Grass (also known as the Battle of the Little Bighorn). His knowledge of these battles and Lakota customs helped him perform in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, a famous traveling show that depicted a glorified version of the Western past and experience. Black Elk joined the show in 1886, and performed for Queen Victoria of England. While in Europe, Black Elk got lost and ended up traveling with the Mexico Joe Show until eventually being reunited with Buffalo Bill. Missing home, he returned to his family.

When Black Elk returned, the Lakota were unhappy because the government was taking their land and the buffalo were almost completely destroyed. Hoping to bring back their way of life, many joined the Ghost Dance Movement. This movement was led by Wovoka (a Paiute Shaman), who told them that performing the Ghost Dance would bring back their traditional way of life. The United States government did not want them to do this, because they had outlawed Native American spirituality and did not want Native Americans to think they would get back their land. They felt threatened by the Ghost Dance Movement's message of unity, spiritual pride, and resistance.

This tension led to the Wound Knee Massacre, which was an attack on a Lakota camp. The Seventh Cavalry killed more than 300 Lakota, and it was so devastating that it destroyed the Lakota's hope that they could ever win against the U.S. government. The Plains Indian wars were over, and the Lakota were forced to live on reservations. Black Elk lived with other Oglala Lakota on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Throughout his life, Black Elk found other ways to be holy and, converting to Catholicism, took the name Nicholas. He hoped that Catholicism would help him heal people like he had done as a Medicine Man. He became a catechist so that he could continue to teach others. Although he was now religiously Catholic, Black Elk maintained his Lakota spirituality and believed in the traditional teachings of his childhood.

The United States was expanding West in the late 1800s, and Lakota life and the lives of many Native American communities began to shrink. The events Black Elk witnessed and the changes in his own life exemplify the changes the United States was going through at the time.

(Image: The Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890 devastated the Lakota Sioux and ended their fight against the U.S. Government)

His Legacy

-

In 1931, Black Elk met John G. Neihardt, an author and poet who was interested in the “Other World” from Black Elk’s teachings. With the help of Black Elk’s son, Benjamin Black Elk, Neihardt interviewed Black Elk about his life and Lakota traditions. In 1932, Neihardt turned these interviews into a book, Black Elk Speaks. This book tells Black Elk’s story – including his vision, healings, and the battles he witnessed – and the stories and traditions of the Lakota people.

In 1931, Black Elk met John G. Neihardt, an author and poet who was interested in the “Other World” from Black Elk’s teachings. With the help of Black Elk’s son, Benjamin Black Elk, Neihardt interviewed Black Elk about his life and Lakota traditions. In 1932, Neihardt turned these interviews into a book, Black Elk Speaks. This book tells Black Elk’s story – including his vision, healings, and the battles he witnessed – and the stories and traditions of the Lakota people.Black Elk Speaks did not become popular right away, but in 1972, John G. Neihardt was interviewed on television by talk show host Dick Cavett. In this interview, Neihardt talked about his relationship with Black Elk and the book on his life. This raised public awareness of the book, and had an effect on the American Indian Movement (AIM). One of the goals of AIM was to get back some of the Native American cultures and traditions that had been lost in the early 20th century. Black Elk Speaks helped people learn about Lakota culture and traditions, and better understand that way of life.

In 2016, Black Elk Speaks continues to bring light to Lakota traditions. One of Black Elk's inspiring lessons is his teaching of the Sacred Hoop (or Medicine Wheel) and the importance of the Circle. The Sacred Hoop is an important symbol of a circle which represents everything in Lakota life, including four sections to represent the four directions and sacred life paths of the Lakota. In Black Elk Speaks, Black Elk describes this symbol in detail and says, “the flowering tree was the living center of the hoop, and the circle of the four quarters nourished it” (121). Places like the John G. Neihardt State Historic Site in Bancroft, Nebraska celebrate the circle in its Sacred Hoop Prayer Garden. The garden includes a tree surrounded by the paths and circle of the hoop in Black Elk’s teachings.

Although there is some controversy over Neihardt's role as an intermediary, Black Elk's teachings have helped preserve many Lakota traditions that could have otherwise been lost. Black Elk Speaks has helped to preserve many teachings that inspire the Lakota community to maintain their way of life, and also helps others who are not Lakota to understand Lakota culture.

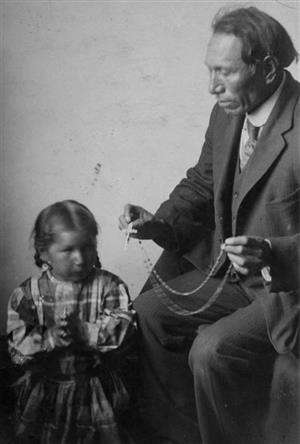

(Image: Later in life, Black Elk converted to Catholicism. Here, he teaches his daughter Lucy about the rosary.)

The Sacred Hoop

-

For the Lakota Sioux, the Sacred Hoop (or Medicine Wheel) is a sacred symbol that represents their lives and values. Black Elk believed in the power and teachings of the Sacred Hoop. It shaped his worldview, and he taught its message to many people during his life. In 2016, these teachings continue to make an impact. The John G. Neihardt State Historic Site in Bancroft, Nebraska celebrates this symbol in its Sacred Hoop Prayer Garden. Designed by Neihardt, the garden is designed to reflect and explain the symbol to visitors.

Additional Information

-

Although he died in 1950, Nicholas Black Elk continues to be a highly influential figure in the Lakota community. While his life was full of the excitement, horrors, and changes of the late-19th-century Great Plains, the impact of his words after his death make him truly notable. Unlike so many other important members of the Lakota community of the period, his words and experiences were thoroughly preserved for the use and growth of American understanding and Native spirituality.

With the help of figures like author John G. Neihardt, Black Elk communicated the Lakota perspective of the Plains Indian Wars. His traditional upbringing and role as Medicine Man also allowed him to speak about the traditions and culture of the Lakota. Neihardt preserved these narratives in his 1932 text, Black Elk Speaks, after extensive interviews with Black Elk. This relationship is not without its controversies, however. If Black Elk’s words were filtered through a translator and a white author, could Black Elk Speaks really claim to represent his true message and experience?

However, it could be said that this relationship between Neihardt and Black Elk demonstrates the potential for collaboration between these groups. The two men seemed to earnestly believe that they were brought together in order to preserve the traditional ways of Black Elk’s people, both for the Lakota community and also in order to create an understanding of their culture within the white community. In this way, Black Elk serves as a bridge to mending the gap in understanding between Lakota and Euroamerican culture.

While there is certainly room to speculate what may have been lost in translation, the 1932 narrative nevertheless impacted a very significant moment in more recent Native American history. In 1972, television personality Dick Cavett interviewed Neihardt, who spoke about the importance of his work with Black Elk and raised awareness of the text. All of this happened at a moment of struggle and renewed tensions between white and Native communities, as the American Indian Movement (AIM) was coming into full force. Not only were members of AIM searching for ways to reestablish their Native identities, but many white Americans were struggling to understand their suffering. Although Black Elk had died more than 20 years earlier, Black Elk Speaks filled a significant need in many American lives.

Today, Black Elk continues to serve an important purpose. It remains a problem that the 19th-century struggle between Native Americans and the U.S. government is perceived as a “clash of cultures”—a perception that perpetuates the idea that these two cultures are impossible to bring together and that conflict between them is inevitable. Black Elk, both in his life and his teachings, illustrates that this is simply not true. He converted to Catholicism in 1904 but maintained his Lakota spirituality and beliefs. For him, the two were not opposing forces but rather two ways in which an individual could express his or her holiness and give thanks to the Creator. He spent his life pointing out what both groups shared in common and what connected them as people.

Due in part to his influence within the Lakota community and also because of his association with Neihardt, there are many locations in Nebraska that speak to Black Elk’s importance. These include the Black Elk–-Neihardt Park in Blair, Nebraska, as well as the John G. Neihardt State Historic Site in Bancroft. While named after Neihardt, the John G. Neihardt State Historic Site is heavily influenced by Black Elk and his teachings. The Sacred Hoop, for example, can be found both in and out of the site’s visitor center. On Aug. 7, 2016, bronze statues were unveiled at the state historic site depicting Neihhardt taking notes during his interviews with Black Elk on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in 1931 and Black Elk with uplifted arms based on a photograph Neihardt took during their visit to Harney Peak in South Dakota. Both of the works demonstrate contemporary appreciation for his life.

Written by Annie Reiva, a history graduate student at the University of Nebraska Lincoln.

2016 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"I've learned so much about the diverse history of Omaha and all its struggles. The best part was the fun field trips. We got to get out and explore the history of North and South O."

- Eva C.

"Making Invisible Histories Visible is a very great program. I've learned so much in only eight days. This has been an amazing experience, we've learned about Jewish, Native American, African American, and Latino history... The best thing was making friends, going to fun places, and just experiencing this great program."- Chloe D.

"The best part of my experience is learning about anything from stacked houses to a deep history of Black Elk. Another one of my best experiences is making friends, not only with people my age but with college students and teachers."-Brett R.

Resources

-

Beasley, Conger, Jr. We Are a People in This World: The Lakota Sioux and the Massacre at Wounded Knee. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

"Black Elk, wičháša wakȟáŋ, of the Oglala Lakota - A Life in Photos." Indian Country Today Media Network. 12 June 2015. https://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/06/12/black-elk-wichasa-wakhang-oglala-lakota-life-photos-160706

Brown, Joseph Epes. The Spiritual Legacy of the American Indian: With Letters While Living with Black Elk. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2007.

Buller, Galen. “The Beauty of the Unbroken Hoop.” Broken Hoops and Plains People: A Catalogue of Ethnic Resources in the Humanities: Nebraska and Thereabouts. Nebraska Curriculum Development Center (1976), 1-46.

Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970.

Carlson, Peter. “Encounter: Buffalo Bill at Queen Victoria’s Command.” HistoryNet. December 2015. https://www.historynet.com/encounter-buffalo-bill-at-queen-victorias-command.htm

DeSersa, Aaron, Jr. and Clifton DeSersa. Black Elk Lives: Conversations with the Black Elk Family, edited by Hilda Neihardt and Lori Utecht. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Holloway, Brian R. Interpreting the Legacy: John Neihardt and Black Elk Speaks. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2003.

Marshall, Joseph M., III. “A Battle Won and a War Lost.” In Legacy: New Perspectives on the Battle of the Little Bighorn, edited by Charles E. Rankin. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press, 1996.

--------. The Day the World Ended at Little Bighorn: A Lakota History. New York, NY: Viking, 2007.

--------. The Lakota Way: Stories and Lessons for Living. Viking Compass, 2002.

“Massacre at Wounded Knee, 1890.” Eyewitness to History. 2009. https://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/knee.htm

Medicine, Bea. “Native American Resistance to Integration: Contemporary Confrontations and Religious Revitalization.” Plains Anthropologist 26, no. 94 (November 1981), 277-286.

Michno, Gregory F. Lakota Noon: The Indian Narrative of Custer’s Defeat. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 1997.

Neihardt, John G. The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk’s Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt, edited by Raymond J. DeMallie. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

Neihardt, John G. Black Elk Speaks: The Complete Edition. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

Research compiled by Eva C., Chloe D., and Brett R.

Eva C., Chloe D., and Brett R. This fall, Eva will attend South High, Chloe will attend Bryan, and Brett will attend Benson. They love food, field trips, and having fun learning Nebraska history!