Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

-

What were the key issues in Native American efforts to advance civil rights, and what strategies and tactics did they employ?

Modern Civil Rights

-

Activism is action taken to create social change. We examined the events at specific places and began to understand the importance of location to social justice for Native Americans. The Red Power Movement was about Native Americans’ civil rights and regaining sovereignty. We focused on three events: Trail of Broken Treaties, the Occupation of Wounded Knee, and the Blackbird Bend Litigation. The Trail of Broken Treaties was an uprising that took place all over the country and ended in Washington D.C. at the White House. The Occupation at Wounded Knee was a battle for Native American sovereignty in Pine Ridge, South Dakota. The Blackbird Bend Litigation was a legal battle over land between the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska and Iowa land owners. Although these three cases are very important to Native American rights, they are not the only cases involving Natives’ rights.

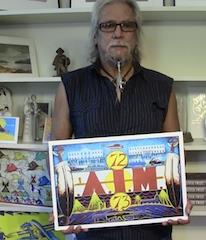

A 5 minute video done in 2104 with Donel Keeler, Omaha artist and participant in Wounded Knee about his experiences fighting for Native American rights in the 1970s.

The Trail of Broken Treaties

-

Before the Trail of Broken Treaties, many Native Americans believed that pressing issues had not been attended to by the Federal Government. Specific complaints included inadequate living conditions, economic inequality, and, most importantly, their treaty rights were not being honored. The trail began with protests in California followed by an auto caravan of Native Americans moving from the West through the interior of the country toward Washington, D.C. On the way they were joined by other protesters they recruited on the way, including in Omaha.

Before the Trail of Broken Treaties, many Native Americans believed that pressing issues had not been attended to by the Federal Government. Specific complaints included inadequate living conditions, economic inequality, and, most importantly, their treaty rights were not being honored. The trail began with protests in California followed by an auto caravan of Native Americans moving from the West through the interior of the country toward Washington, D.C. On the way they were joined by other protesters they recruited on the way, including in Omaha.The purpose of the Trail of Broken Treaties was to draw attention to the Native Americans' needs. The Natives' caravan was organized by eight Native associations that brought together Natives from all over the country to come together to protest in Washington D.C. Their goal was to meet with President Nixon but he refused to meet the protesters.

The Native American protesters took over the Bureau of Indian Affairs in hopes of finding shelter and to bring attention to their cause. They created a 20-point position paper which stated they wanted treaties to be revisited and compensation for past events when treaties had been violated.

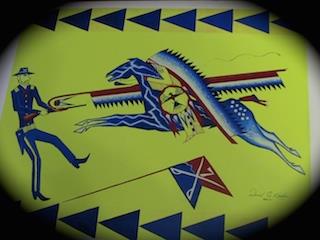

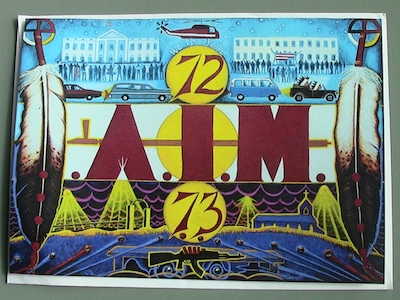

Ultimately, the standoff ended when the government agreed to look into the 20-points. The most positive outcome of this protest was the media attention that the group received. The Trail of Broken Treaties was one of the first national protests for Native American rights and is regarded as an influential event in Native American activism. (Artwork courtesy of Donel Keeler).

Wounded Knee

-

On Feb. 27, 1973, the Lakota Sioux began protesting for Civil Rights at the occupation of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Pine Ridge Reservation borders the northwest corner of Nebraska. Two hundred people from the reservation wanted Richard Wilson, Tribal President, out of office because he was showing favoritism toward his family and other European-mixed Native Americans. Wilson not only favored certain people over others, he also was seen as a tool of the federal government. Without the best interests of the Lakota people at heart, he was known for being corrupt and using physical violence against his “enemies.” Additionally, protesters wanted to renegotiate past treaties that had not been honored by the federal government.

On Feb. 27, 1973, the Lakota Sioux began protesting for Civil Rights at the occupation of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Pine Ridge Reservation borders the northwest corner of Nebraska. Two hundred people from the reservation wanted Richard Wilson, Tribal President, out of office because he was showing favoritism toward his family and other European-mixed Native Americans. Wilson not only favored certain people over others, he also was seen as a tool of the federal government. Without the best interests of the Lakota people at heart, he was known for being corrupt and using physical violence against his “enemies.” Additionally, protesters wanted to renegotiate past treaties that had not been honored by the federal government.Wounded Knee was chosen for the occupation because of the terrible memories of the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. In this event, 300 Sioux were massacred by the United States Army. Occupying this land on Feb. 27, 1973, the Lakota Sioux and other Natives who were a part of the American Indian Movement (AIM) came together to protest the treatment of Native Americans on the reservation. During the occupation, the protesters held 11 of the Oglala Sioux hostage to attract media attention and to draw awareness of the Native American experience. Donel Keeler, Omaha artist and participant in Wounded Knee, described the occupation as “Survival. The firefights would happen at night. It was just a war. It was the first time…I was at war with the United States government.” During the siege, two Native Americans were killed by federal agents sent to disband the occupation and one federal agent was shot by the Natives and eventually died.

Due to the federal agents' death, the government cut off supplies to the protesters and, without food and water, negotiations began to increase. By May 8, 1973, the occupiers surrendered. Many of the protesters left without legal action taken against them, but occupation leaders were arrested. In 2014, one still remained in prison for the Occupation at Wounded Knee.

After the battle was over, Richard Wilson remained in office, and the violence continued (it even escalated) on the Pine Ridge Reservation. While Native Americans continued to fight for their civil rights, the occupation attracted a lot of media attention and allies from the non-Native community. The Occupation at Wounded Knee will remain a significant example of Native American activism. (Photograph of Mr. Donel Keeler, artist).

Blackbird Bend

-

During the Red Power Movement, several Native American groups known as the American Indian Movement (AIM) had a series of confrontations with the Federal Authorities. This included the Occupation of Alcatraz Island from November 1969 - June 1971, The Trail of Broken Treaties in 1972, and the Occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973.

One of the least known events during this time was the Blackbird Bend Litigation. According to the 1854 treaty with the Federal Government, the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska owned the land near Blackbird Bend on the Missouri River. Over time, the river changed its course and 11,000 acres of land that once belonged to the Omaha in Nebraska was now in Iowa. The U.S. Government started selling this "new" land to the people of Iowa.

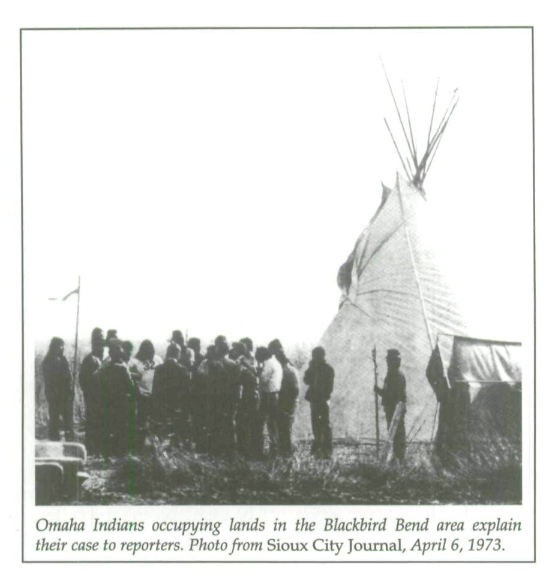

In an attempt to get this land back, the Omaha Tribe sent a notice to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in 1966. With little action from the BIA, the Omaha Tribe was driven to further protest. In April 1973, the Omaha Tribe occupied the land, protesting that it was rightfully theirs, and the Iowa landowners brought their attorneys. The photograph below shows Omaha protestors explaining their case to members of the press. The photograph was taken on April 6, 1973. (Photograph courtesy of the Sioux City Journal) By May, the trial had begun in Federal District Court. Nothing had been decided in 1975, so the Omaha reoccupied Blackbird Bend. After a series of torturous and emotional trials, the case was moved up to the Supreme Court of the United States and back down again to the District Court. In 1990, a decision was made; the Omaha would receive only a small portion of the land equaling 2,200 acres.

Even though the Omaha Tribe had only a partial victory, the Blackbird Bend Litigation opened the country's eyes to Native American rights. It also demonstrated the completion of legal issues between Natives and the federal and state governments. While this court case only addresses land rights, many other rights are still being fought for.

Additional Information

-

Like many civil rights movements of the 1960s, the American Indian Movement brought their struggle for cultural understanding and justice to the forefront of political discussion throughout the United States. Modern Native American activism traces back to the founding of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) in 1944. The NCAI was one of the first groups to effectively build a national alliance of Native Americans across tribal lines. Under the leadership of Vine Deloria Jr., the NCAI became a vocal critic of the poor treatment of American Indians, particularly urban Indians, in the mid-1960s. Growing out of the NCAI's efforts, activists in Minneapolis founded the American Indian Movement (AIM) in 1968. The very first AIM programs in Minneapolis replicated the Black Panther Party's efforts to end police brutality by monitoring police actions and assisting vulnerable Native Americans. A shift in tactics occurred when Native American activists occupied Alcatraz Island in 1969 during an effort to reclaim the island. Inspired by the successful protest, AIM activists began to move to more high-profile protests in order to garner support through the national media, similar to what African-American activists had done throughout the 1960s. Native American activists launched a series of protests that drew on culturally significant lands such as Plymouth Rock in 1970 and Mount Rushmore in 1971. These public displays of direct action were a drastic change from the more restrained efforts of NCAI, which continued to fight for justice through legal and legislative efforts in addition to grassroots organizing. AIM protests like the Trail of Broken Treaties in 1972, Occupation at Wounded Knee in 1973, and the legal battles surrounding the river shift at Blackbird Bend beginning in 1966, reveal the efforts of Native American activists and their supporters in their pursuit of justice.

During the 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties, AIM protesters caravanned from California to Washington D.C. bringing attention to and demanding action against the disrespected treaties forged throughout the centuries after colonization. In the months to follow, the American Indian Movement made its way to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota (the site of the Massacre at Wounded Knee) to protest the violence, discrimination, and sub-human treatment of Native Americans. Lasting 71 days, the Occupation at Wounded Knee resulted in the death of protesters and federal officials alike, while attracting national attention and support for the cause. Participant, Donel Keeler, recalled the event as a kind of civil war--"it was the first time we [were] at war...with the federal government." Inspired by his interview, students delved into their research with an intensity and interest that produced a clear understanding of the events' influence.

In a display of local activism, the Omaha tribe became embroiled in a legal fight for land sovereignty lasting over two decades. The Blackbird Bend litigation traces the legal battle over 11,000 acres of land reappropriated with the shift in the Missouri River. An 1854 treaty with the federal government gave the Omaha people a track of land along the Missouri River including the area termed "Blackbird Bend." By the 1960s, the peninsula at Blackbird Bend shifted and Iowa farmers claimed the land as their own. In a 1966 notice to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Omaha tribe requested the land be returned to their reservation. With no consideration from the federal government, the Omaha pursued the issue in what would become a 20-year battle for land sovereignty. Ultimately, a 1990 decision gave the Omaha people 2,200 acres of the original 11,000. Research on this case introduced students to legal case study and anchored Native pursuits of sovereignty in the land and events occurring 'close to home.'

Emphasizing the influence land can have on creating, maintaining, and re-discovering identity--both personal and communal--these three demonstrations of Native American activism allowed students the historical context to consider identity as 'space.' Interviewing Donel Keeler proved an invaluable experience for the students as they were able to connect the national events with personal experience--the process, inspiring greater interest in the subject matter. Students cultivated research, academic-writing, and video production skills, while developing an interest in cultural studies. 'Modern Activism," forged, as one student wrote, "a want to always fight for the rights of other people." Another expressed a desire to be an activist herself.

2014 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"In this program, I learned the importance of peoples rights. I learned that Native Americans had a hard life and that they constantly had to fight for their rights. I hope I will always remember the important history of their tribes, and I hope I myself can stand up for everyone’s rights."

- Bella O.

"The best experience about Making Invisible Histories Visible was connecting our identity to Native Americans. It made me think about my own identity. Who am I? What is my goal? What can I do to make my future bright? What kind of community do I need to live in to make it come true?"- Jon’Tavia B.

"I knew that Native Americans had to fight for their rights in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but I did not realize it was still an ongoing struggle. Through studying our three events I have realized that for Native Americans having a place is very important to having a sense of community. It is so important they are willing to put their life on the line for sovereignty."- Madison S.

Resources

-

"AIM occupation of Wounded Knee begins." History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 18 July 2014. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/aim-occupation-of-wounded-knee-begins.

Chertoff, Emily. "Occupy Wounded Knee: A 71-Day Siege and a Forgotten Civil Rights Movement." The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, 23 Oct. 2012. Web. 18 July 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/10/occupy-wounded-knee-a-71-day-siege-and-a-forgotten-civil-rights-movement/263998/.

Heppler, Jason. "Framing Red Power." Framing Red Power. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1 Jan. 2009. Web. 18 July 2014. https://www.framingredpower.org/narrative/tbt/.

Scherer, Mark R.. Imperfect victories the legal tenacity of the Omaha Tribe, 1945-1995. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press, 1999. Print.

Research compiled by: Jon'Tavia B, Isabella O, Madison S, Tierney P and Bridget M