Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

-

How did the contributions of Senator Edward Danner to the civil rights movement help improve the lives of citizens in his local community, the city of Omaha, and the State of Nebraska?

-

On Valentine’s Day in 1900, Edward R. Danner, the 10th son of Mack Danner and Annie McGee was born to a family of former slaves from Como, Mississippi who had relocated to the plains of Oklahoma. In Danner's youth, a white man, who claimed to be acting in self-defense, shot down two of his brothers and was acquitted of their murder. In 1918, Edward moved north to Nebraska and never returned.

On Valentine’s Day in 1900, Edward R. Danner, the 10th son of Mack Danner and Annie McGee was born to a family of former slaves from Como, Mississippi who had relocated to the plains of Oklahoma. In Danner's youth, a white man, who claimed to be acting in self-defense, shot down two of his brothers and was acquitted of their murder. In 1918, Edward moved north to Nebraska and never returned.When Danner arrived in Omaha he decided to stay with a brother who already lived there. He got a job at the Swift and Company packinghouse. Danner had at most an eight-grade education but his fellow packinghouse workers considered him wise and pragmatic. “He knew where talk ends and action begins.” Serving as vice-president of his labor union, the United Packinghouse Worker's of America (UPWA), helped to prepare Danner for negotiating with the state government.

In 1963, he decided to help another union officer run for District 11 in North Omaha. However, the local people spoke out, preferring that Danner run instead. His union supported Danner in his run and eventually got him elected. The first thing he did in the Unicameral was to get an old law prohibiting interracial marriage repealed. Afterwards, he worked on a fair jobs bill that made it possible for people of color to be employed and be paid equally. He wanted people to have fair opportunities and chances at a better life.

Danner represented North Omaha for seven years before suffering a heart attack and passing away in 1970. Edward Danner may have passed away, but he still lives on in our minds and our local justice system. He will always be remembered as the man who represented the community during a tumultuous but important period.

Published on July 22, 2016

Students created this documentary as part of the Omaha Public Schools Making Invisible Histories Visible initiative.

Danner in the Union

-

For 38 years, Edward Danner worked as a butcher in the shadow of the Livestock Exchange Building. Due to unequal treatment of minorities, Danner began fighting for fair wages and equal treatment through the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA).

Being both a butcher and an African American in the meatpacking business, Edward Danner experienced discrimination in the workplace first-hand. During most of the 20th century, minorities who worked in the stockyards performed their jobs just as well as the white men who worked there, but the white men were often paid more and treated better. Danner wanted equal pay and conditions for all workers. As a result, Danner, along with other Swift meatpacking workers, decided to do something about it. They joined a union, went on strike for equal pay, and fought for an end to racial discrimination in the workplace.

Danner belonged to The United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA). In 1950, the UPWA created an Anti-Discrimination Department dedicated to ending racial discrimination in meatpacking plants and working against segregation. Danner saw how the union was attempting to help workers negotiate and settle grievances, and joined the fight against discrimination when he saw the effectiveness of the group.

Because of his passion for justice, his coworkers elected him as the executive supervisor of the union board. Over the years, he served several terms as a field representative for the international union and would later become vice president of the UPWA. His time in the union representing minority workers would later prove to be a valuable experience when he pursued a career in politics and served as a Nebraska State Senator.

In 1963, Edward Danner was elected by the 11th District to represent their largely African American community in the Nebraska State Legislature. Among many other civil rights issues, Danner worked to pass the Nebraska Fair Employment Act of 1965. This act made it illegal to discriminate against workers based on their race. It also ensured that employers paid all workers a fair and equal wage regardless of their race.

Turmoil in North Omaha

-

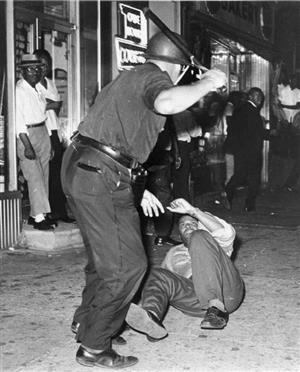

Unrest and police brutality during Danner's tenure.

Unrest and police brutality during Danner's tenure.Police brutality against minorities was an all too familiar scene in Omaha and in many larger cities across the United States during the 1960's.

In the 1960s, many large, urban cities across America were racially tense. Omaha was no different—periods of unrest and riots occurred as concern for civil rights increased. Senator Edward Danner actively fought to equal the playing field between the races. He was strongly opposed to police brutality, especially when it involved minorities.

The first clash between police and teens in Omaha was during the summer of 1966. The police officers came upon some African American youths hanging out in front of a grocery store. Approximately 60 young African Americans were arrested for unknown reasons. In the following days, many protestors demonstrated in North Omaha, only to be silenced by the National Guard on the third night.

In 1969, Omaha police killed a black teenager named Vivian Strong. The forensic evidence showed that she was fleeing a gathering that had been broken up by the police when she was shot in the back of her head near the base of her neck. Businesses were burned and looted as a sign of protest in the wake of the attack.

Danner stood on the floor of the Nebraska legislature and declared that two African American boys were detained after allegedly throwing ice at police cruisers. He said that the police refused to let the boys contact their parents, handcuffed them, beat them with Billy clubs, and called them racial slurs.

Violations of civil rights like these were becoming a very familiar scene in Omaha and across the country. At the time, Danner was trying to amend a bill that would require the police to notify the parents of juveniles in custody and prevent police from abusing them while in custody. Poor communication between the police and the community led to mistrust. Through this legislation, Danner tried to prevent future beatings and killing of minors, as well as bridge communication between the government and the people.

Danner fought for equality and fairness, especially in regard to law enforcement. Unfortunately, when analyzing the friction between the Black Lives Matter movement and the police, it appears little has changed over the last 50 years, as our country continues to struggle with civil rights.

Danner's Legacy

-

A scholarship, the NEOC, and the E.R. Danner/Kountz Park Neighborhood Association.

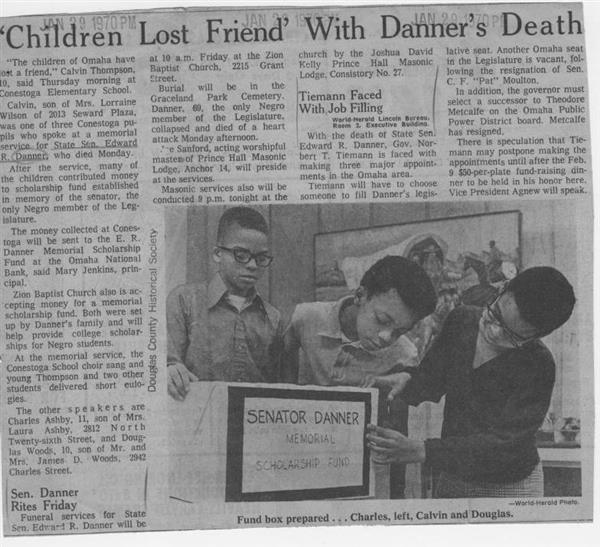

As the newspaper article suggests, when Senator Danner passed away, many children lost a friend. However, in 2016, his scholarship continues.

Edward R. Danner suffered a sudden heart attack on Jan. 1, 1970, in a parking lot at 17th and Jackson streets in Omaha. He passed away later that day at the age of 69, and a funeral was held at his home church, Zion Baptist. He is buried at Graceland Park Cemetery in Omaha.

At the funeral, Nebraska Governor Norbert Tiemann summed up Danner’s importance to the state, saying, “His efforts have not only benefited the Black Nebraskan, but have also served to make the white Nebraskan aware of the needs of his Black brothers.”

To honor this influential African American politician and his achievements, the United Methodist Church formed a scholarship, ‘The Senator Danner Scholarship”. It is designed to help low-income, minority families pay for college by identifying high school seniors who demonstrate academic excellence and leadership potential. Applicants who reside in Nebraska Legislative District 11 are given preference.

By passing the Fair Housing Practices bill in 1969, Senator Danner created the Nebraska Equal Opportunities Commission. This is a group that helps Nebraskans understand and protect their civil rights. The main function of this commission is to investigate charges of unlawful discrimination.

While Danner made many contributions to his community, these two important legacies continue to have a positive impact on the North Omaha community he so proudly served.

-

From 1963 to 1970, Edward R. Danner, a mild-mannered former butcher and packinghouse activist, was the sole Black voice in the Nebraska legislature. He represented the 11th District, which constitutes the majority of North Omaha. Due to a long history of segregation, the district that Danner represented was the vibrant but overcrowded home to nearly 90 percent of the state’s Black citizens. As a state senator, Danner fought the social and political isolation that had long characterized North Omaha, but police and community tensions and a series of riots that led to the wholesale abandonment of the area by the white and Jewish business-owners complicated his career significantly. Senator Danner’s Fair Housing Practices bill, passed in 1969, effectively opened up the rest of the city to Omaha’s Black residents.

Danner’s successes were always hard-fought in the conservative all-white legislature of the 1960s, but he eventually won over white political allies during a Lincoln coffee-shop sit-in and an official investigation into poverty within his district. Danner led senators from all over the state on a fact-finding tour of North Omaha in 1963, showing many their first glimpses of urban poverty. The Omaha Sun perhaps described him best in their 1965 profile of the senator, “He knows where talk ends and action begins . . . His articulateness [is] the sort that gives a voice to the inarticulate.” Though Edward Danner claimed to be ‘no philosopher,’ and often understated his own role in the local movement, he was a natural leader who followed the model established by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the nonviolent approach to civil rights activism. He was a thoughtful person who believed in human dignity and an active application of Christian principles. He sought to uplift the people of North Omaha and Nebraska more generally through negotiation, determination and a fundamental belief in the democratic process.

By 1968, Danner had helped to pass at least three major civil rights bills, including the repeal of Nebraska’s ban on interracial marriage. His other major campaigns addressed the racist real estate practice of redlining, as well as equal pay for city workers regardless of race. However, Edward R. Danner wasn’t merely a member of the Unicameral, though he may have been one of the most important members in the state’s history for his civil rights work alone. In MIHV, our group endeavored to go beyond his work in Lincoln to uncover more personal details, getting at the hardworking and humble individual that Danner really was. We got to know that person largely through his grandson, the Reverend William Williams, to whom we owe an immeasurable debt of thanks. Yet we also touched on a few topics that helped to illuminate some of the more complex aspects of Danner’s career: namely his union activism, his responses to police brutality and rioting, and his ongoing legacy in North Omaha and in the state of Nebraska.

“My experience participating in union negotiations prepared me to understand legislative processes and methods,” Danner wrote in 1965, “The union supported my candidacy and I suppose that was the deciding factor in my decision to run.” For Danner, who came to Omaha from rural Oklahoma as a young laborer, union participation was a natural bridge from obscurity and poverty to large-scale political and social activism. Starting on the killing floors at Swift and Co. In the mid 1920s, he gradually climbed from local to national leadership of his union, the United Packinghouse Workers of America. The UPWA enacted anti-discrimination campaigns in the South Omaha packinghouses in the aftermath of World War II. As early as 1950, the left-leaning UPWA officially fought for equal pay for both women and minorities in the meatpacking industry. Through his role as a negotiator and advocate for workers, Danner became a popular and respected figure. When he tried to campaign for a friend in 1962, the people of his neighborhood instead insisted that he run.

Like his grandson, Rev. Williams explained, Danner’s early advocacy for “equal pay for equal work” transitioned easily from the labor movement to politics. In his first few years, Danner had already proved himself a tremendous advocate for the poor (the legislative fact-finding tour of North Omaha) as well as a catalyst to challenge Nebraska’s “equal pay” and “equal accommodation” statutes. One development that the UPWA may not have prepared him for, however, was the increasing tension between Black youths and the Omaha Police Department in the mid-1960s. In the sweltering summer of 1966, the mass arrest and police beatings of groups of Black teens ignited two riots. The National Guard was called in after a number of businesses on North 24th Street were burned and white and Jewish-owned shops were looted, accelerating the tide of white flight out of North Omaha.

We cannot confirm exactly how Danner mediated between the Black community and Mayor A.V. Sorensen, but we know that he approached the situation with a measured tone and spoke out against violence on both sides. He advocated for the Omaha Police to treat Black youths with humanity and respect and also lobbied to improve the treatment of juvenile detainees who were often beaten and rarely allowed to contact their parents. Significantly, Danner helped to prevent any rioting in North Omaha after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, but that victory proved to be short lived and Danner turned his attention to ending the practice of redlining and de facto racial segregation.

Police and community relations in North Omaha continued to fray in the last years of Danner’s life. The worst riots in North Omaha’s history were sparked by one of the worst instances of police violence in Nebraska’s history: the fatal shooting of 14 year-old Vivian Strong at the Logan Fontanelle Housing Project. Large portions of 24th Street were burned to the ground as a result. Shortly after, at the age of 69, Edward Danner suffered a fatal heart attack in a downtown parking lot. Danner’s final civil rights legislation was the Fair Housing Practices Act that effectively ended the period of overt housing segregation in Omaha. Rev. Williams also emphasized that a large part of his legacy was the creation of the Nebraska Equal Opportunities Commission to enforce many of the civil rights laws he had helped to pass.

While Edward Danner was laid to rest in Graceland cemetery, Vivian Strong’s death and the aftermath of the riots continued to grip the community. The officer who had shot Vivian Strong was exonerated and let off with a light fine. Meanwhile, a young activist named Ernie Chambers was arrested after a campaign of police surveillance and harassment at his 24th Street barbershop, Goodwin Spencer. By this time, a new generation of Black activists and politicians had come of age to continue Danner’s fight against segregated housing, poverty and wage discrimination and were themselves seeking political office. Six months after Senator Danner’s death, with the support of his daughter, Marion Danner Williams, the North Omaha activist Ernie Chambers was elected to replace Danner in the 11th District. Chambers continued to represent North Omaha for 35 terms in the Unicameral. Many members of Danner’s extended family, including grandchildren and great-grandchildren, continue Edward Danner’s legacy through their involvement in Omaha’s contemporary political and religious life.

While researching Senator Danner, our MIHV students studied the issues from his era closely and we had wonderful, insightful conversations about poverty, police brutality, and the right to choose who you would like to marry, where you would like to work, and where you would like to live. Beyond looking at Danner as a legislator and the issues of his day, we also got to visit the City Offices thanks to Douglas County Treasurer John Ewing, who was gracious enough to give us his perspective as both a former cop and a contemporary black politician. Once again, our interview with Danner’s grandson, Rev. William Williams was absolutely crucial to the project. Along the way, we taught the students the skills of conducting oral history interviews, writing historically, and thinking critically about place.

To that end, we explored and examined Danner’s district from Kountze Park and King Science Center to Goodwin Spencer and Zion Baptist Church. None of our students had spent much time in North Omaha before and what they did know about the area was largely influenced by the negativity of the evening news. Needless to say, we believe all three students walked away with a new perspective on their city and the vast potential that it holds.

Edward Danner fought many a long and difficult battle to ensure that North Omaha would not become a politically or socially forgotten place. Today many, many wonderful people, from county treasurers to restaurateurs, continue this important endeavor. Not only are these folks reigniting North Omaha with vibrancy and stewardship, but they were also kind enough to spend time with us as well, offering their stories and their perspectives. Though our investigation was a brief one, it was our immense privilege to get to know Danner, the person and the legislator, but also his district’s past, present and future.

Written by Quin Slovek.

2016 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"Going through this process I have learned more than I thought I would. I can finally be proud of where I'm from due to the rich culture of Omaha. I have come to see this place not as cold and dull but lively and vivid. My perspective on Omaha and its history has changed tremendously. I now feel like I can brag about where I live."

- Drake H.

"MIHV is an awesome opportunity to learn and make friends. Through the interviews I gained public speaking practice and oral history skills. The tours of Omaha were both fun and educational. This program showed me the roots of Omaha due to its rich North and South Omaha cultures. I learned about the positivity of North Omaha and it's citizens. I also discovered many decades of unfairness in this community but that many people are trying to change that to make things more equal. Coming into this program I knew nothing about Omaha's history. Coming out of this has changed my whole image of Omaha. I now have a new respect for my city."-Serena B.

"MIHV was like a day camp for students who don't want to stop learning. I discovered that if you go outside of your comfort zone, you can make a lot of great friends and learn more things by talking to different people. I always though Omaha was just some boring, old town but now I realize that I am surrounded by so much history that I never knew was there. This program has changed me in a lot of ways but now my eyes are more open and they no longer see just buildings but historic monuments."- Ezmi B.

Research compiled by Drake H. with Serena B. and Ezmi B.

Serena B., Drake H., & Ezmi B. photographed with Douglas County Treasurer John Ewing and Teacher Jeff S.