Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

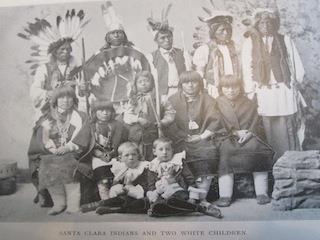

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Native Americans in the Military

-

Why does the military service of Native Americans continue to be an invisible history?

Native Americans in the Military

-

Do you know about Native Americans in the military? A proportionally large percentage of Native Americans have served. In 2012, 1.4 percent of the population of the United States was Native American. However, 1.7 percent of all active-duty servicemen are Native American. Some Native Americans faced discrimination while serving in the United States military. Other members of the military mocked the Native Americans by calling them Chief and making them do rain dances. Although Native society honors veterans, their history is invisible to many Americans. There are very few monuments and written histories of Native American veterans. Here on this site, you will learn about the veteran pow-wow, code talker Walter C. John, and Col. Tom Brewer.

A 13 minute video done in 2014 interviewing Native American veterans Eugene Papan (Korean War); Steve Tomayo, Rich Barea (Vietnam); Malcom Tyndal (War Chaplain); Owen Webster (Vietnam). Talk about the significance of eagle feathers in their headdress.

2014 UmonHon Powwow

-

On July 12, 2014, in Carter Lake, a pow-wow took place. This powwow has been going on now for four to five years and it honors veterans. UmonHon Veterans Association would like to keep this powwow going on for a long time.

On July 12, 2014, in Carter Lake, a pow-wow took place. This powwow has been going on now for four to five years and it honors veterans. UmonHon Veterans Association would like to keep this powwow going on for a long time.Most traditional powwows start with a grand opening. If a veteran is present, they will carry the eagle staff and flags. Once the staff enters with the flags, then it is the dancers' turn to enter. The order of the dancers is head dancers, men's traditional, men's grass dance, men's fancy, women's traditional, women's jingle and women's fancy. Teens and kids would line up in the same order. The Master of Ceremonies would invite all people to come and dance. If you ever go to a powwow, the drums will be in the middle of the arena. Although most powwows would not do this, the UmonHon believe that the drum beats represent the heart of a human. There are seven people on a drum. The head drummer would face the Master of Ceremonies, then his second drummer would be on the left hand of him instead of the right. The drummers are also the singers of the powwow.

Code Talker Medal of Honor

-

Silver and gold medals such as the one shown were awarded to the Santee Sioux code talkers. The gold medals they were awarded are kept at the Smithsonian and silver medals were awarded to individual veterans who fought in the Armed Forces as code talkers. On Nov. 20, 2013, 33 different tribes were awarded these medals. Due to the secret nature of their work, it has taken roughly 65 years to recognize these Native American veterans of World War II.

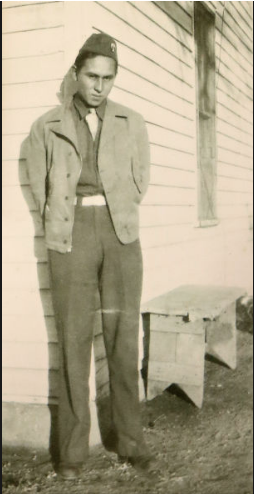

Silver and gold medals such as the one shown were awarded to the Santee Sioux code talkers. The gold medals they were awarded are kept at the Smithsonian and silver medals were awarded to individual veterans who fought in the Armed Forces as code talkers. On Nov. 20, 2013, 33 different tribes were awarded these medals. Due to the secret nature of their work, it has taken roughly 65 years to recognize these Native American veterans of World War II. One of the winners of this medal was Walter C. John. Born in 1920 in Santee, Nebraska, John was a member of the Santee Sioux Nation. He entered the United States Army on Oct. 15, 1941, and served in World War II. He was a member of the First Cavalry Division and fought in the Bismark Archipelago, New Guinea, and the Southern Philippines. John was a Santee Sioux code talker and used his native language to help guide his fellow soldiers. Code talkers like John, speaking in their native languages, were able to relay secret messages by radio between U.S. troops. The Japanese and German translators were unable to understand their languages and the communications were safely delivered without enemy interception. Having been sworn to secrecy by the Army, Walter C. John never told his family about his work as a code talker. Only after he died did his family learn fully of his heroism and his work as a code talker. In 2013, Walter John's family received on his behalf the Congressional Medal of Honor for his service in World War II. He received the silver Medal of Honor and his tribe, the Santee Sioux, received the gold Medal of Honor.

One of the winners of this medal was Walter C. John. Born in 1920 in Santee, Nebraska, John was a member of the Santee Sioux Nation. He entered the United States Army on Oct. 15, 1941, and served in World War II. He was a member of the First Cavalry Division and fought in the Bismark Archipelago, New Guinea, and the Southern Philippines. John was a Santee Sioux code talker and used his native language to help guide his fellow soldiers. Code talkers like John, speaking in their native languages, were able to relay secret messages by radio between U.S. troops. The Japanese and German translators were unable to understand their languages and the communications were safely delivered without enemy interception. Having been sworn to secrecy by the Army, Walter C. John never told his family about his work as a code talker. Only after he died did his family learn fully of his heroism and his work as a code talker. In 2013, Walter John's family received on his behalf the Congressional Medal of Honor for his service in World War II. He received the silver Medal of Honor and his tribe, the Santee Sioux, received the gold Medal of Honor.(Medal Photos Courtesy of US Mint, Photo of Walter C. John Courtesy of The Sioux City Journal, accessed 12/5/18)

Colonel Thomas Brewer

-

Col. Tom Brewer was born in 1958. He is the oldest of Alice DeWolf, a member of the Oglala Sioux tribe, and Ross Brewer, who served in the Korean War (1950-1953). Tom Brewer grew up on a farm near Gordon, Nebraska and graduated from Gordon High School in 1977. In the same year, he joined the Nebraska National Guard. Brewer served as a volunteer firefighter in Murdock. Tom Brewer served in Operation Desert Storm in 1990 and in Afghanistan in the 2000s. While serving with the 10th Mountain Division and 3rd Special Forces Group in Afghanistan, he was shot six times during a 45-minute firefight. During another tour in Afghanistan in 2011, he was wounded by a rocket-propelled grenade. After retirement, Brewer became active in politics.

(Photo Courtesy of the Nebraska State Historical Society)

Additional Information

-

Native Americans have a long and rich history of service in the United States military. In the modern era, Native Americans have seen duty in every U.S. conflict from World War I to the engagement in Afghanistan. A variety of factors pulled Indigenous veterans towards service, including cultural, educational, and economic factors. Although they have represented a relatively small percentage of the U.S. population, they have served in comparatively large numbers. Despite their impressive record of service, the modern history of Native Americans in the U.S. military remains relatively hidden. In popular memory, Indigenous servicemen are remembered as code talkers, yet they have played various roles in the military. There are also few stories and no monuments attesting to their sacrifice. In Omaha specifically and Nebraska generally, the story of Indigenous servicemen remains a truly invisible history.

In modern history, Native Americans have served in disproportionately large numbers in the U.S. military. In 2012, Native Americans represented only 1.4 percent of the population; however, they constituted approximately 1.7 percent of the population of the U.S. military. This disproportionately large Native presence in the military is not a recent phenomenon. Although the United States government did not grant them citizenship until 1924, some 12,000 Native Americans volunteered for service in World War I. During World War II, more than 44,000 (out of a population of roughly 350,000) Native Americans served, with 99 percent of all eligible Indigenous men registered for the draft by 1942. Another 10,000 Native Americans served in the Korean War, and during the "Vietnam War, 90 percent of the more than 42,000 Natives who served in the military during that conflict were volunteers."

As these statistics demonstrate, a relatively large number of Native Americans voluntarily served in the United States military, yet what inspired them to fight for a government that had historically brutalized their people? The persistence of a strong warrior society answers part of that question. According to Robert Holden, the deputy director of the National Congress of American Indians, "it's the warrior culture. Warriors have always been in our presence and always will be... not only in times of conflict, but in times of peace as well. They became the leaders." Economic and educational opportunities have also drawn Indigenous peoples to military service. The GI Bill, which was created in the wake of World War II and provides post-secondary education in exchange for military service, has acted as a draw for many Native Americans seeking to gain an education and escape the poverty that plagues their society.

The most prominent narrative of modern Indigenous service is that of the code talkers, particularly that of the Navajo code talkers. However, Native American servicemen filled a number of roles in the U.S. military, often during the same tour. For example, during World War II, Nebraska's Hollis Stabler was assigned to the 2nd Armored Division, 67th Armored Regiment and became a crew member of an M3 Stuart tank. He remained with his tank unit throughout the campaigns in North Africa and the invasion of Sicily, but later joined the Army Rangers as a radio operator during the invasion of Italy at Anzio. During the invasion, Stabler was wounded and received the Purple Heart. He later became a member of the 1st Special Service Force and participated in the invasion of southern France. Stabler represents a counter-narrative to that of the code talker due to the fact that he was not a code talker and filled a number of roles while in the military.

While constructing our project, it became increasingly evident how hidden the history of Native American military service in Nebraska remains. Many of the newspaper articles our students found were obituaries that detailed the experiences of veterans second-hand. It was only in the last three decades and after these Indigenous veterans had passed that the dominant culture noticed their history. Literary accounts of Nebraska's Native veterans are a little better. There are a number of histories that cover the Native American military experience generally in the 20th century, but there is no history of Nebraska's Indigenous veterans, and memoirs such as Holls Stabler's are still rather rare.

This is not an absence solely in written accounts; there are few spaces dedicated to Nebraska's Indigenous veterans. In creating their projects, the students wrote about the historical significance of a space in relation to their topic, yet as we began searching in the Omaha area, no spaces became apparent. There is no monument dedicated to Omaha or the region's Indigenous veterans, and we were unable to find less visible locations related to this history. The students ultimately attended the Umon Han Veterans Association powwow at Carter Lake and used the grounds as their historical space since it is owned by the Umon Han tribe. However, we would not have known about the powwow had it not been for the help of local Native American veteran Steve Tomayo. Without Tomayo's help, our group might have been unable to find a space related to our subject. Just as Nebraska's Native American veterans are absent from the written record, there are no spatial markers attesting to their service. For many of Nebraska's Indigenous veterans, the spaces in which they live fail to speak to their history of service and sacrifice.

2014 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"I learned about how Native Americans faced & are facing discrimination. Like the veterans we interviewed Richard Barea said they called him chief and Owen said they said "Go out there and to the rain dance." The best part of this camp were the interviews. Plus the work we did helped us understand Native American culture and we get an elective credit for high school."

— Tyreek C.

"I have a better understanding of native people that are not in the history books. I have a different thought on the Indian mascots and how some tribes like to have their tribe as a mascot and others do not. I also met veterans who told me stories about when they were in combat."— Ziggy I.

"I thought that this program was going to be boring & it turned out to be fun and educational. We got to go out of town and go to Lincoln, the capital of Nebraska. We had a lot of special guests including, Jerome Kill Small and Patrick Jones as guest speakers. This program is a great way to learn about different heritages, cultures and to have fun!"— Jordan W.

Resources

-

Bernstein, Alison R. American Indians and World War II. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991).

Britten, Thomas A. American Indians in World War I: At Home and at War. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1997)

Holm, Tom. Strong Hearts Wounded Souls: Native American Veterans of the Vietnam War (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999)

Lemay, Konnie. "A Brief History of American Indian Military Service." Indian Country Today. March 28, 2012. https://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2012/05/28/brief-history-american-indian-military-service-115318

Stabler, Hollis. No One Ever Asked Me: The World War II Memoirs of an Omaha Indian Soldier. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005).

Research compiled by: Ziggy I., Tyreek C., Jordan W.