Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

African American Athletes & Facilities

-

What barriers and stereotypes had to be broken down in order for Black athletes from Omaha and elsewhere to play in integrated professional sports?

Athletics and the African American Community

Sports in Omaha

-

Sports are a large part of the community for fans and non-fans alike. Sports give young people a sense of hope. More importantly, it can keep young kids busy and out of gangs and away from drugs. African Americans have fought to desegregate sports teams, destroying racial barriers. It wasn’t just the athletes that fought for these rights. Many Black people in the community became united and helped to make young African American athletes' dreams realized. When some of those athletes became professionals, they exhibited a sense of pride they earned through proving themselves to white athletes. Over the years, whites became more accepting of them, and the stereotype that whites are better than Blacks was destroyed. Black athletes became heroes in their communities and across the country.

Some African American athletes would never be discovered if they had given up before they tried. If it wasn’t for segregated sports leagues, African Americans wouldn't have been able to play sports. If it wasn’t for athletes who broke the color barrier, we might not be able to play professional sports as young African Americans. Black athletes never gave up, no matter what happened. They played in the Negro leagues until they were able to play professionally. Even after they were able to join the white teams, they still weren't allowed to do the same things as white players. Sometimes they couldn’t stay in the same hotels, they had to eat in separate rooms, and they had to use different showers. It took time for these barriers to break down. African American athletes never listened to people who said they would never make it and continued to excel in their fields. These African American players worked hard so that other African Americans could play professional sports.

An 8:14 interview in 2011 with Dr. Don Benning talking about his role as a University of Nebraska at Omaha (UNO) wrestler, then head UNO Wrestling Coach and assistant football coach. He fought to have Marlin Briscoe start at quarterback for UNO’s team. The best player, but people at the time did not think Blacks were smart enough to play quarterback. The Calvin Jones interview talks about Black athletes in the 1980s who showed him he could go to college through athletics.

August 14, 1936

Segregated Baseball in Omaha

-

Omaha sports in the early 20th century were rigidly segregated – sometimes violently so. Several local baseball leagues existed, and all were segregated by the turn of the century. Blacks from the Omaha Colored Leagues almost never played white teams. A big day for the Negro League was when Satchel Paige and his Negro League All-Star team came to Omaha. Paige was a star and his coming to Omaha was a pretty big deal. The park was packed. (Omaha World-Herald photo courtesy Douglas County Historical Society)

On August 13, 1936, Paige's All-Star team played a local white team, the "Bearded Sons of David", at Rourke Park (also known as Western League Athletic Park) at 13th and Vinton streets. Paige's team was victorious, and the stadium was burned to the ground in the hours following the game. Even small steps towards racial integration during this time were greeted with anger and violence by many townspeople.

Changing Faces

-

In the mid-20th century, high school sports in Omaha weren’t segregated by law (de jure), but more so by practice (de facto). Black athletes were often the first ones cut and were generally discouraged from participating. Over the years, involvement by African American athletes slowly increased in high schools, as coaches allowed more and more Black players on the team. The process of integration is visible on the walls of North High School. Pictures of the 1956 championship football team and the 1967 championship football team can be compared to show the changes. You can also see this integration in the world-renowned athletes that these schools produced. Omaha South High School had Marlon Briscoe, Omaha Central had Gale Sayers, and Omaha Tech had Bob Gibson, Ron Boone, and Johnny Rodgers. These athletes didn’t only open a door for their schools, but they did for other schools and other African American athletes. You can go to any of these schools and see that there is only one or two African American kids in the photos, but over the years the number of African American athletes has increased.

The change in athletes did not take place in isolation from the rest of society. A marquee moment in high school sports integration occurred at the same time as a tumultuous time in the larger North Omaha community. The 1968 Omaha Central boys basketball team (known as the Rhythm Boys) was the first in the state to put out an all-Black starting lineup. Just days before the state tournament, George Wallace came to the Omaha Civic Auditorium and sparked a riot that destroyed property in North Omaha. One of the starters for the Central team was arrested (charges were eventually dropped) during the mayhem and the tournament was moved from Omaha to Lincoln to avoid further violence. The Central team had to play with the riot from home weighing heavily on their minds.

Trailblazers

-

Athletes who worked to break down racial barriers and achieve inspired athletes who followed them. Calvin Jones in his interview talked about some of the local athletes who rose to prominence. Bob Boozer, Marlin Briscoe, Gale Sayers, Johnny Rodgers, and Joe Orduna of the 1970s. Then Larry Station, Richard Bass, Keith Jones, and Leotis Flowers of the 1980s, and lastly Calvin Jones, and Ahman Green of the 1990s. The later athletes built on the foundations of the athletes who came before them.

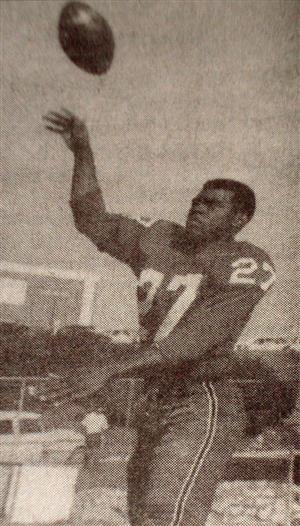

Athletes who worked to break down racial barriers and achieve inspired athletes who followed them. Calvin Jones in his interview talked about some of the local athletes who rose to prominence. Bob Boozer, Marlin Briscoe, Gale Sayers, Johnny Rodgers, and Joe Orduna of the 1970s. Then Larry Station, Richard Bass, Keith Jones, and Leotis Flowers of the 1980s, and lastly Calvin Jones, and Ahman Green of the 1990s. The later athletes built on the foundations of the athletes who came before them.In the 1950s and '60s, many African American athletes paved a path for wider participation in high school sports. Several of these Black Omahans would go on to break barriers on the national level. Don Benning is a multi-sport athlete who went to North High, where he was the only Black wrestler on a state championship team. He would later go on to Omaha University (today called University of Nebraska at Omaha-UNO), to become the first Black wrestling coach at a predominately white college. He was also an assistant football coach, where he came in contact with a talented quarterback named Marlon Briscoe (who came to UNO from Omaha South High, pictured). Briscoe would go on to the NFL, where he would become the first starting Black quarterback in the NFL in 1968, his rookie year. Despite setting records for the most touchdowns, owners were still skeptical about a Black quarterback and Briscoe had to play wide receiver. Briscoe and Benning would prove that African Americans were more than capable of being leaders on and off the field. (Photo from the Douglas County Historical Society Archives)

George Bryant Basketball Center

-

African American children all over the country have gone to places where they could play and hang out with their friends. Some of these places in North Omaha are Kountze Park, the North-Side YMCA, the Bryant Center, and other rec centers. The Bryant Center was built in 1966 and adults and children have been playing on it ever since. This center was built after the civil unrest of that year. It was built because young people demanded a place to play. These places keep young people out of trouble and give them something to do. At these centers, neighborhood kids were mentored by coaches to work hard and it would pay off. Due to these places being built, kids had a safe place to play and grow into young adults.

Additional Information

-

Sports played a prominent role in the integration of society as a whole, as they allowed multiracial interactions that were oftentimes nonexistent elsewhere. Even with the successes of Black athletes on both the local and national stage, African Americans still face many hurdles in the sports world. For instance, despite native Omahan Marlin Briscoe breaking the barrier in 1968, Black quarterbacks are still rare, and are often pushed to play other positions as they move up to higher levels. With the Denver Broncos, Briscoe became the first Black starting quarterback in the NFL, stepping in for an injured starter. After breaking the rookie record for touchdown passes in a season (14), he was cut by the Broncos before the next season. He went on to be an All-Pro receiver with several other NFL teams, but never played quarterback again despite his success. Briscoe's career, like those of many other Black athletes, serves as an unfortunate reminder that integration did not end with a few athletes breaking barriers, but is a process that continues to this day.

2011 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"You can learn many things from living everyday life. But when you learn from your role models it's way more inspirational and somewhat puts an impact on your life."

— Tay H.

"This program is a big eye-opener to me because people may think there is only racism in the South but there is way more in-depth than that about racism all across the USA and with this program, I now know that."

— Samad M.

"By taking this course I learned a new meaning to the word community. Instead of just a neighbor or a neighborhood that you live in I learned that community is something deeper. I learned that back then community wasn’t just your neighbor it was people helping each other."— Alex W.

Resources

-

Briscoe, Marlin with Bob Schaller. The First Black Quarterback. (Grand Island, NE: Cross Training Publishing, 2002).

Gibson, Bob with Phil Pepe. From Ghetto to Glory: The Autobiography of Bob Gibson. (New York: Popular Library, 1968).

Gibson, Bob with Lonnie Wheeler. Stranger to the Game. (New York: Penguin, 1994).

Howard, Ashley M. "Then the Burning Began: Omaha, Riots, and the Growth of Black Radicalism, 1966-1969." MA. Thesis., University of Nebraska-Omaha, 2006.

Marantz, Steve. The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central: High School Basketball at the '68 Racial Divide. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011).

Miller, Patrick B. "The Anatomy of Scientific Racism: Racialist Responses to Black Athletic Achievement." in Sport and the Color Line: Black Athletes and Race Relations in Twentieth-Century America ed. Patrick B. Miller and David K. Wiggins. (New York: Routledge, 2004).

Sayers, Gale with Fred Mitchell. Sayers: My Life and Times. (Chicago: Triumph, 2007).

Special thanks to Dr. Don Benning and Ashley Howard for their assistance on this project.

Research compiled by: Alex W., Samad M., Tay H., and Bill Deardoff.