Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

African Americans in Vietnam

-

How were Black soldiers both in war zones and back home during the Vietnam era?

Heroic Citizens: The Black Experience in Vietnam

Military Service Vietnam

-

America began taking direct military action in Vietnam in 1964 and ended the draft and signed the peace accords in 1973. North Vietnam and South Vietnam were at war over the issue of communism. This conflict was a continuation of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. The United States supported South Vietnam because it was non-communist.

This controversial conflict created tension in the United States, which coincided with social, political, and racial unrest. The United States military drafted many African Americans to fight in Vietnam. This website celebrates the lives and contributions of Omaha’s Black Vietnam Veterans.

A 5:12 video produced in 2011 with interviews of Black Vietnam veterans Denise Wilson and Porter Pittman and info on Milton Ross who was killed in action.

Milton Alan Ross

-

Army Private First Class, Milton Alan Ross, was born Sept. 9, 1948, to Muriel L. Maroney and Norman Ross in Omaha, Nebraska. He attended Central High School and graduated in 1966. The United States Army drafted him into the military in April of 1968. Ross went to Vietnam on Jan. 6, 1969, and died in combat on Feb. 9, 1969.

In 1967, Charles Evers, the state director of the Mississippi NAACP, criticized state officials for maintaining “lily-white” draft boards. In 1966, the NAACP demanded proportional racial representation on all draft boards. As a result of the disproportionality, Black men in the military died 60 percent faster. In Vietnam throughout 1966, 11 percent of the U.S. fighting force was black, but African Americans made up 17.8 percent of overall combat deaths. From Oct. 1, 1966, through Dec. 1, 1966, the U.S. tallied that 576 of the 3,145 deaths were of African Americans. Economic struggles and poverty compelled Black men to become primary candidates for being drafted into the military.

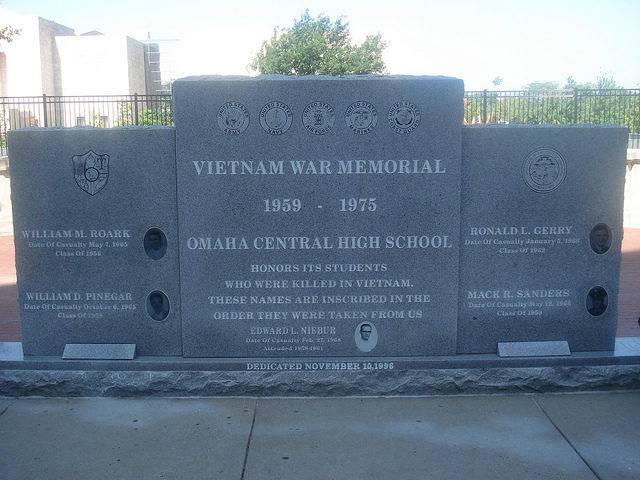

Picture of Milton Alan Ross on the Central High Vietnam Memorial

Contributions Made by African-American Soldiers from Omaha

-

The Purple Heart (PH) is awarded to a soldier that has been either injured or killed in action. The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is the next level above the Purple Heart. This recognition is for heroic or meritorious achievements or service. The Oak Leaf Cluster (OLC) is presented to those soldiers that have earned more than one Purple Heart or Bronze Star Medal.

Although African Americans struggled with racial equality, they made significant contributions during the Vietnam War. Engraved on Milton A. Ross' headstone are letters BSM, PH and OLC. Many African American troops received numerous medals but were not recognized in the mainstream media. Black newspapers, like The Omaha Star, are significant because they published news from the Black community. The following is a list of troops whose accomplishments were celebrated in The Omaha Star. In 1967, Blaine A. Wilson received the Air Force Commendation Medal. In 1966, George H. Williams received the Vietnam Service Medal and James E. Prater received the Bronze Star. Porter Pittman was awarded the Purple Heart during his 26-month tour in Vietnam. During 1969, the same year that Milton A. Ross won his Purple Heart and Bronze Star, Maurice T. Craddock received the Purple Heart, Vietnam Service Medal, Army Accommodation, and the National Defense Air Medal. All of these African American men are from Omaha.

The house at 2424 Hartman Avenue where Milton A. Ross lived.

In the 1960s and '70s, America still struggled with segregation. As a result, while soldiers fought for freedom in Vietnam, African Americans were fighting for civil rights at home. At the same time, African American soldiers fought in integrated units in Vietnam. The soldiers ate, slept, and died together, no matter what their skin color. However, when they came home, they still lived in segregated communities. The picture shows the home of Milton A. Ross, a soldier that fought in the Vietnam conflict. He lived in the Black community in North Omaha. Today, African Americans are not segregated by law but still make up the majority of the population in North Omaha. Even after African Americans like Ross fought and died in integrated military units, many neighborhoods, like his, remain segregated. Although there is a memorial at Central High School honoring the graduates who died in service, the lack of commemoration in the community at large shows that many of these individual histories have been forgotten.

Additional Information

-

The Vietnam War was the first conflict in modern American history that was fought by fully integrated armed forces. The American military was in many ways a reflection of American society. Continuing racial disparities and racial tensions in the 1960s and 1970s affected the armed services as well.

The students’ work highlights the life and death of Milton Alan Ross, one of the many African Americans who perished in Vietnam. Black men made up roughly 10 percent of the U.S. Army, where Ross served, but as a result of their scores on standardized tests, were funneled into high-risk combat roles rather than support units. This systemic racism was accompanied by instances of personal racism, in which a number of white officers discriminated against African Americans. As a result, prior to 1968, one-third of all U.S. troop casualties were African Americans.

The students’ discussion of Ross’ home life draws a distinction between life in combat and non-combat environments. On the battlefield, Black and white soldiers often worked as a cohesive unit in the tense wartime situation. However, when they returned to their bases or returned home, racism became readily apparent again. In 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, which sparked the greatest racial hostility in the history of the U.S. military. Major racial conflicts occurred in Vietnam at Cam Ranh Bay, aboard the USS Kitty Hawk, at military bases in the U.S., and elsewhere.

One should also be mindful of the experience of African American soldiers returning home. Following the conflict, many African Americans had difficulty taking advantage of the benefits of the G.I. bill. As a result of systemic and personal racism and, in some cases, bad behavior, Black soldiers received less than honorable discharges at a disproportionate rate. This either reduced or made them ineligible for benefits. Moreover, the benefits of the G.I. Bill have been significantly reduced since World War II. Because roughly 90 percent of African American Vietnam veterans came from working-class or poor families, they were less able to afford school on the benefits offered. They also experienced greater unemployment rates than white veterans, perhaps reaching 30 percent. However, others returned to have productive and meaningful lives.

Finally, one should be cognizant of the role of African Americans in resisting the Vietnam War. Many African Americans volunteered at higher rates in the early years of the conflict and viewed draft resistance as cowardly. However, as Americans became increasingly disillusioned with the conflict, African Americans played an important role in resisting the ongoing war. No previous war provoked as great a range of African American dissent.

A 2011 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"I used to think history was just dates and periods where things that happened before I did, and just another thing to learn. But it actually matters."

— James O.

"These histories have gone invisible and it was nice to help them shed their cloak."— Morgan H.

"We went to look for Milton A. Ross' grave. To our surprise, this hero had a stone covered in grass and dirt. Ross was a decorated soldier [of the Vietnam War] whose history was really invisible but now I feel like his story is found. It is significant to me because I was the one to clean a hero's grave!"— Hannah P.

Resources

-

Black, Samuel W., ed. Soul Soldiers: African Americans and the Vietnam Era. Pittsburgh, PA: Pittsburgh Regional History Center and the Smithsonian Institution, 2007.

Boulton, Mark. “How the G.I. Bill Failed African-American Vietnam War Veterans.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education 58 (Winter, 2007/2008): 57-60.

Graham, III, Herman. The Brothers’ Vietnam War: Black Power, Manhood, and the Military Experience. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003.

Westheider, James E. Fighting on Two Fronts: African Americans and the Vietnam War. New York: New York University Press, 1997.

Research compiled by: Hannah P., James O., Morgan H., and Carol Simon