Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Funk Music

-

How did funk music reflect the political and social experiences in Omaha?

Nothing But the Funk

-

Funk is a type of music that originated in African American culture during the second half of the 20th century and mixed elements of soul, R&B, jazz and blues into a new rhythmic, danceable genre. During the Civil Rights Movement, when there was a lot of racial tension, funk was the counterculture. Funk bands in Omaha didn’t let racism or prejudice stop them. While African American culture was central to the birth and evolution of funk, over time, as the genre gained popularity, the music and scene around it became increasingly integrated. The bands were still racially integrated and included female members. A local Omaha band, Square Biz, had a woman lead singer and L.A. Carnival was one of the first integrated bands in Omaha. Funk lyrics emphasized integration, freedom, love, peace and having a good time.

Another way funk set the bands and artists apart from everyone else was by their appearance. The clothing funk musicians wore had a meaning behind it and allowed them to express themselves on stage as well as put the fun in funk. Bell bottoms, platform shoes, bright colors and psychedelic patterns were common and important. The clothing was as significant as the music because both alluded to not only the individuality, but also the community of funk. Omaha was home to a vibrant funk scene from the 1970s through the 1990s.

Published during the Summer of 2018

Video: 15 min video interviewing Robert Holmes Sr. (Square Biz), Reyford Jones and Juan Lively (Lively, Holmes & Jones – LHJ) and Ron Cooley (Les Smith Soul Band and L.A. Carnival) about the history of funk music and the places they played in Omaha.

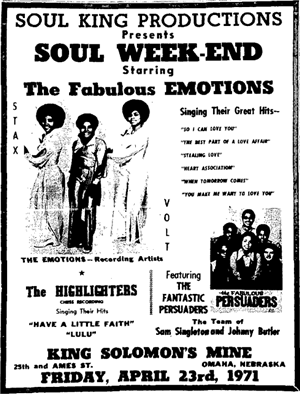

Soul Week-End at King Solomon’s Mines

-

King Solomon’s Mine, located at 25th Street and Ames Avenue, became a popular hotspot for funk music from its grand opening on Oct. 28, 1970, to its final closing date in 1972. During its short lifespan, promoters used flyers like this one, which informed the community that King Solomon’s Mine was hosting an upcoming event, “Soul Week-End,” on April 23, 1971. The event featured several local funk bands, including “The Fabulous Emotions” and “The Highlights,” who performed some of their most well-known hits, like “Stealing Love,” “Lulu,” and “When Tomorrow Comes.” In 2018, the building that housed King Solomon’s Mine remains intact as an industrial warehouse. (Image Courtesy of NorthOmahaHistory.com)

King Solomon’s Mine, located at 25th Street and Ames Avenue, became a popular hotspot for funk music from its grand opening on Oct. 28, 1970, to its final closing date in 1972. During its short lifespan, promoters used flyers like this one, which informed the community that King Solomon’s Mine was hosting an upcoming event, “Soul Week-End,” on April 23, 1971. The event featured several local funk bands, including “The Fabulous Emotions” and “The Highlights,” who performed some of their most well-known hits, like “Stealing Love,” “Lulu,” and “When Tomorrow Comes.” In 2018, the building that housed King Solomon’s Mine remains intact as an industrial warehouse. (Image Courtesy of NorthOmahaHistory.com)

Allen’s Showcase

-

Allen’s Showcase, located in the heart of Omaha’s African American community at 2229 Lake St., was a famous hotspot for funk and jazz bands in Omaha from the 1950s to the 1980s. In the historically segregated part of Omaha, this venue set the stage for funk musicians and bands to give their audiences memorable nights. Allen’s Showcase attracted large crowds that loved what integrated funk bands like L.A. Carnival and musicians, like James Brown and Rayford Jones, brought to them. After it closed in 1986, the space that was formerly Allen’s Showcase has housed a series of other businesses, including a fried chicken restaurant and other music venues, like Papa G’s and BJ’s Showcase. (Image Courtesy of Patricia Allen)

Square Biz

-

Square Biz was an Omaha-based funk band during the 1970s and 1980s. Their outfits from this image clearly date them to this period. The outfits that the artists had on included leather jackets, leather pants, and fedoras, unique pieces popularized through funk music. Chuck Miller organized the band and was also responsible for forming other popular funk bands in Omaha at the time, like ETC and Jam Squad. Importantly, Square Biz also had a female lead singer, Denise Taylor. While funk continued to be largely dominated by Black men, the broader funk culture ultimately found space for women vocalists and instrumentalists, as well as white and Latino players and patrons, an important distinction in the post-1960s era. The most famous of this kind of mixed lineup was Sly and the Family Stone. (Image Courtesy of A Bridge to Success)

Square Biz was an Omaha-based funk band during the 1970s and 1980s. Their outfits from this image clearly date them to this period. The outfits that the artists had on included leather jackets, leather pants, and fedoras, unique pieces popularized through funk music. Chuck Miller organized the band and was also responsible for forming other popular funk bands in Omaha at the time, like ETC and Jam Squad. Importantly, Square Biz also had a female lead singer, Denise Taylor. While funk continued to be largely dominated by Black men, the broader funk culture ultimately found space for women vocalists and instrumentalists, as well as white and Latino players and patrons, an important distinction in the post-1960s era. The most famous of this kind of mixed lineup was Sly and the Family Stone. (Image Courtesy of A Bridge to Success)

LA Carnival Album Cover

-

L.A. Carnival was a popular funk band local to Omaha in the 1960s and '70s. The band began their career as the Les Smith Soul Band, led by Leslie Smith. However, when Leslie Smith was drafted into the army, Lester Abrams changed the name to L.A. Carnival. While L.A. Carnival was given the opportunity to contribute to the national funk scene after releasing two singles, “Blind Man” and “Color,” the majority of its members couldn’t leave Omaha because they had student deferments and would be drafted to Vietnam. Therefore, it was not until 2003 when L.A. Carnival experienced a resurgence and released their album “Would Like to Pose a Question.” Nevertheless, the loud, eccentric graphics on the album cover capture the personality of funk and everything that the band was in the 1960s and '70s. (Image Courtesy of Ron Cooley)

L.A. Carnival was a popular funk band local to Omaha in the 1960s and '70s. The band began their career as the Les Smith Soul Band, led by Leslie Smith. However, when Leslie Smith was drafted into the army, Lester Abrams changed the name to L.A. Carnival. While L.A. Carnival was given the opportunity to contribute to the national funk scene after releasing two singles, “Blind Man” and “Color,” the majority of its members couldn’t leave Omaha because they had student deferments and would be drafted to Vietnam. Therefore, it was not until 2003 when L.A. Carnival experienced a resurgence and released their album “Would Like to Pose a Question.” Nevertheless, the loud, eccentric graphics on the album cover capture the personality of funk and everything that the band was in the 1960s and '70s. (Image Courtesy of Ron Cooley)A .41 video of Ron Cooley talking about integrating funk bands with women and white musicians.

A 3 minute video on the Vietnam War and the effects on the funk band members (some were drafted) and their songs.

Additional Information

-

Music has always been an intricate form of expression, used to articulate the deepest human emotions and convey messages about experiences ranging from love to oppression. When mainstream protests became less apparent in the 1970s and '80s, after the calamity of the civil rights movement, the Black community turned to music to voice their discontent and a new genre of music emerged – funk. Though funk, like jazz, was initially dominated by African American voices and sounds, it carried a message of integration and love for one another. James Brown is often coined the ‘Father of Funk.’ He took the musical stylings and emotion of jazz and added a strong backbeat. Laid on top of the upbeat orchestration were typically lyrics expressing a deeper meaning than one that would match the groovy beat. This was intentional because it allowed the messages in the lyrics to be more widely spread. The positivity emanating from the beat and the lyrics showed the band's optimistic outlook on their ability to make a change.

Funk became a counterculture not only in its rhetoric but also in the lifestyle associated with the funk scene. Many bands were integrated in a time where racial tensions were high and uneasiness still surrounded some of the ground gained during the civil rights movement. Sly and the Family Stone were one of the most popular integrated bands, but they also accentuated women’s representation by placing women in lead roles and set an example not only for other funk bands, but for the nation. Individualism and embracing one’s uniqueness was a defining factor of funk seen through the song lyrics and the way the bands presented themselves, including their clothes. The expressive outfits worn by funk groups emphasized their open-mindedness and effort to reject the social norms of the time. This national definition of funk diffused into cities across the nation and, as was characteristic of funk, it was molded and adapted to make it their own.

Though the Omaha funk scene looked similar to the national one, there were many ways it differed. Omaha started its funk craze a little later than the rest of the nation, with its main funk scene existing from the late ’70s to the early ’90s. In terms of its culture, funk has always been an eclectic mix of very African American sounds and rhythms with almost futuristic integration and styling. L.A Carnival and Square Biz were examples of this kind of futurism. The former was one of the first integrated bands in Omaha, and the latter was one of the first with a female lead singer. In Omaha, a lot of funk culture stemmed from the Black culture of the day. This could possibly be because Omaha has always been very strictly segregated or perhaps it was just a lingering message from the civil rights movement. Very few venues for funk existed past 72nd Street in Omaha, and though some funk bands played past that line, it was rare that the Black members were allowed for any reason other than entertainment. For this reason, most funk groups played at Allen’s Showcase, King Solomon’s Mines, Sandy’s Escape or other venues that existed within North Omaha, though this didn’t mean that the funk community in and of itself was not highly integrated. Because of funk’s nature as a counter-culture, they often tried to subvert what was “normal” and offered a juxtaposition to the social norms of the day.

This adversity perhaps was one of the reasons why the funk community in Omaha was as tight-knit as it was, everyone knew each other, and funk in Omaha was very much a family. Personal identity was as important as ever though, even within a community such as this. Funk music was a very individualized genre, with solos for players and the costuming each employed to show their own brand of uniqueness. This was seen in many of the funk players, like Robert Holmes, and Ron Cooley. However, one detrimental part of this was that the uniqueness they craved usually pulled them away from the closeness of the Omaha scene in search of larger and more active cities, to try and gain a personal spotlight. Though some made it big in those cities, what they experienced there was much the same. Omaha was similar historically to these larger cities. Coming off the end of the civil rights movement, funk was stuck in a place of trying to exhibit joy in the face of adversity, and also speaking about the African American experience of being ostracized in their own nation and cities.

2018 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"Through this process, I learned what funk is and what it meant to people. What funk means to me is community and coming together despite the odds. The odds being segregation and racial tension. Community is important because it allows us to see each other as people and not colors."

- Layla A.

"During this program I have grown to love the experience of meeting magnificent people who have lived through challenging and tough times in Omaha."- Nina K.

"This program was so much fun. I was able to learn so much about funk music and meet different people that I would have never met without being in this program."- Ximena M.

Resources

-

Associated Press. Cynthia Robinson of Sly and the Family Stone Dies at 71. The Hollywood Reporter, The Hollywood Reporter, 3 Dec. 2015.

Album covers and band pictures courtesy of Juan Lively and Ron Cooley.

“King Solomon's Mines Grand Opening.” Omaha Star, 22 Oct. 1970, p. 8.

Miller, Chuck. A Bridge to Success: One Man's Vision Changed the Lives of Many. 2010.

“L.S. Movement Thunder Band Has Triumphant ‘Homecoming’ at Showcase Lounge.” Omaha Star, 11 Nov. 1982, p. 7.

Photographs of Allen’s Showcase courtesy of Patricia Allen.

“The Showcase Lounge is Back.” Omaha Star, 21 Oct. 1982, p. 7.

Sasse, Adam Fletcher. A History of King Solomon's Mines in North Omaha. North Omaha History, WordPress.com, 11 Jan. 2018.

Sasse, Adam Fletcher. A History of the Near North YMCA in North Omaha. North Omaha History, WordPress.com, 7 Feb. 2018.

Sasse, Adam Fletcher. A History of the North Omaha Gene Eppley Boys Club. North Omaha History, WordPress.com, 11 May 2017.

Additional teaching resources for funk music history are available through TeachRock.org

Research combined by Ashlyn-Jordan B., Kayona J., Michael M., Layla A., Ximena M., & Nina K.

Students who worked on the project will attend high school at Bryan High School, Central High School, and Burke High School.