Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche

-

How was the effort to gain recognition of Native American personhood and citizenship rights a cooperative one?

Omaha: Against the current.

-

Since early European explorers first stepped foot in North America, the political current was pushing against Native Americans, who were often viewed as an obstacle to “progress” and considered “savages” or “without souls” by many non-Natives. As a result, they faced mistreatment, discrimination, and forced removal by the government from the lands they called home.

Despite these challenges, Native peoples have consistently fought back in an attempt to maintain their lands, preserve their culture, ensure their rights, and determine their own destiny.

The Omaha Indian tribe, whose name means “against the current,” shares its title with the city of Omaha. In the Nebraska Territory, the Omaha Indians peacefully coexisted with the Ponca tribe as well as non-Natives, yet they continued to be challenged by a government that continued to apply pressure to conform to the white man's ways. By the late 1800s, one Ponca Indian Chief, Chief Standing Bear, motivated by love for his son, his people, and his land, joined in this push to change the current of oppression. His plight stirred the hearts of many Native Americans as well as non-Natives and left a legacy of justice, perseverance, and empowerment for all Native American peoples.

A 2 minute video interview produced in 2014 with Suzette Freivogel and Carolyn Johnson, great nieces of Susette La Flesche Tribbles

Chief Standing Bear

-

Chief Standing Bear was born in a Ponca village near where the Niobara and Missouri Rivers meet. These rivers meet on the borders of Nebraska and South Dakota. Chief Standing Bear was the last generation of the traditional Ponca. The tribe harvested the fruits of the land, fished, and hunted animals like the buffalo. Life was good for the Ponca, living as they had for hundreds of years, but this is only the beginning of a tragic story for this tribe. The Ponca will be driven like cattle from their ancestral homeland, but Standing Bear will prove himself, his tribesmen, and Natives are men.

In 1858, the Ponca tribe signed a treaty with the U.S. government that inadvertently gave the Ponca homeland to an enemy tribe. The government moved the Ponca to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma because the government thought the Sioux would attack the Ponca to gain the remaining land.

Chief Standing Bear, a chief of the Ponca tribe, agreed to go to Oklahoma. The Ponca did not find the land in Oklahoma good to grow their crops and desired to go back home. Angered, the government agents told the Ponca they could walk back to Nebraska if they would not settle in Oklahoma. When the Ponca returned home, the government said they couldn’t stay, and the government pointed guns at them and forced them back to Oklahoma. On the way back down they were faced with harsh weather and rough roads; this is known as the Ponca Trail of Tears.

Chief Standing Bear’s son, Bear Shield, died in Oklahoma. Bear Shield’s dying wish was that his father bury him at the ancestral tribal burial grounds. A small band of the tribe began walking back to Nebraska. When Standing Bear and his band arrive in Omaha, General George Crook ordered them to detain Standing Bear and his men. Hearing of this story, Thomas Henry Tibbles, a news reporter for the Omaha Daily Herald, went to Standing Bear and asked him to file a writ of Habeus Corpus. Soon Standing Bear filed the writ and the case went to court. Chief Standing Bear arrived in court carrying a tomahawk, symbolic of his warrior spirit and the fight he was about to undertake. In the end, the court sided with Standing Bear and ruled that he was a man. After the ruling, Standing Bear dropped his tomahawk to show the end of this “war."

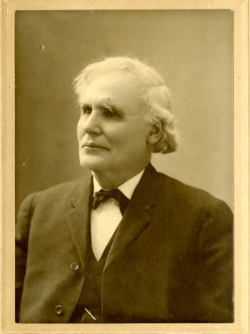

Thomas H. Tibbles

-

Thomas Henry Tibbles was born May 22, 1840 near Athens, Ohio to William and Martha Tibbles. Tibbles was only 16 when he fought with the Union in Bleeding Kansas in 1855 and 1856. Once he was caught by Confederacy forces, he was supposed to be hanged, but escaped. Then he joined two groups of anti-slavery activists. First was the future Republican senator James H. Lane, who led an anti-slavery militia in the Kansas Territory. Second was John Brown, who planned to steal slaves and take them to freedom, but then died in a horrible way. Tibbles also spent some time in Indian camps during this time. He later served for the Union in the Civil War as a freelance writer and newspaperman. Next, Tibbles was a circuit preacher and lecturer in the cause of the Native Americans.

Thomas Henry Tibbles was born May 22, 1840 near Athens, Ohio to William and Martha Tibbles. Tibbles was only 16 when he fought with the Union in Bleeding Kansas in 1855 and 1856. Once he was caught by Confederacy forces, he was supposed to be hanged, but escaped. Then he joined two groups of anti-slavery activists. First was the future Republican senator James H. Lane, who led an anti-slavery militia in the Kansas Territory. Second was John Brown, who planned to steal slaves and take them to freedom, but then died in a horrible way. Tibbles also spent some time in Indian camps during this time. He later served for the Union in the Civil War as a freelance writer and newspaperman. Next, Tibbles was a circuit preacher and lecturer in the cause of the Native Americans.Standing Bear and his Ponca tribe were driven off their lands in Nebraska. The Ponca were forced to go to Oklahoma and live there. After a year in Oklahoma, Standing Bear’s son died and his wish was not to be buried in this foreign land. Standing Bear and 29 of his men walked from Oklahoma to Nebraska to bury his son. The group was stopped in Nebraska and held at Fort Omaha by the army, led by General Crook. T.H. Tibbles, a journalist and newspaper reporter for the Omaha Daily Herald, found out what happened to Standing Bear and his people. General Crook is reported to have had a conversation with Tibbles outlining the plight of the Ponca. Tibbles talked to Standing Bear, convincing him to file a writ of habeas corpus. Habeas corpus is used to determine if the person’s imprisonment or detention is lawful.

At the start of the trial, Tibbles and Susette La Flesche, who served as Standing Bear’s interpreter during the court proceedings, publicized the plight of the Ponca in local newspapers in an effort to attract public support and legal aid. In response, two Union Pacific lawyers, Andrew Jackson Poppleton and John Lee Webster, volunteered to take the case to U.S. District Court in 1879. Throughout the trial, Tibbles and La Flesche continued to publicize the unlawful removal of the Ponca from their lands, as well as the poor conditions and bad treatment they faced during the ordeal. After the trial, La Flesche accompanied Tibbles on a speaking tour about the case. The couple got married in 1882.

The story of Thomas Tibbles is important for many reasons. First, his efforts helped lead to the recognition of Native Americans as persons under the law. Second, his role in the Standing Bear case is an example of Native and non-Native cooperation in the early period of civil rights activism. Lastly, the case highlights the courage and determination of Native Americans and their allies to stand for Indian rights and defend their way of life.

Susette La Flesche Tibbles

-

Susette La Flesche Tibbles, also known as "Bright Eyes," was born in Bellevue, Nebraska in 1854, the year the Omaha Indians gave up their Nebraska hunting grounds and agreed to move to a northeastern Nebraska reservation. Susette was the eldest daughter of Joseph La Flesche. Known as "Iron Eyes," Joseph was the last recognized chief of the Omaha tribe.

Susette La Flesche Tibbles, also known as "Bright Eyes," was born in Bellevue, Nebraska in 1854, the year the Omaha Indians gave up their Nebraska hunting grounds and agreed to move to a northeastern Nebraska reservation. Susette was the eldest daughter of Joseph La Flesche. Known as "Iron Eyes," Joseph was the last recognized chief of the Omaha tribe.Susette was raised on the Omaha reservation where she attended the Presbyterian Mission Boarding Day School located in Bellevue, Nebraska. There, she learned to read and write English. Susette expressed a desire to further her education and arrangements were made for her to attend a private school in New Jersey. Three years after Susettee graduated, she became a teacher at a government school on the reservation.

In 1877, the Ponca tribe was forcibly removed from their land to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Iron Eyes’ mother was Ponca so he went to the Indian Territory to investigate the conditions under which the Ponca were living, and Susette went along. When they returned, Susette worked with Thomas H. Tibbles of the Omaha Daily Herald to publicize the Ponca’s plight. Tibbles convinced Standing Bear, Chief of the Ponca tribe, to file a writ of habeas corpus against General George Crook. Habeas Corpus is used to bring a detainee before the court to determine if the person’s imprisonment or detention is lawful.

Susette was the interpreter for Standing Bear during his trial in U.S. District Court in Omaha in May 1879. It was after the trial that Susette became known as “Bright Eyes.” Tibbles organized a speaking tour of the eastern United States for Standing Bear, Bright Eyes, and her brother, Francis La Flesche. Bright Eyes and Tibbles were married in 1882 and continued their tour of the east and other places.

So who was Susette “Bright Eyes” La Flesche Tibbles?

Susette was a quiet yet strong, independent woman who was a fuse waiting to be lit. She got her spark when she saw how her mother and the rest of the Ponca were living in poor conditions in the Indian Territory. When Susette returned home, she and Tibbles made it their mission to tell about the unfair situations Native Americans faced. On her quest to help her fellow people, she was the interpreter for Standing Bear and aided him in getting his rights.

Susette was a strong advocate for Native American rights. In Susette’s family, a piece of her strength and iron will continue to be passed on for generations, showing to the world the importance of “girl power.” Susette has left a deep mark on history through her fight for justice and equality for her people.

Additional Information

-

The Standing Bear trial has been widely publicized and is often seen as an early victory for civil rights, but the truth is that this is a victory for basic human rights, not just civil rights. Standing Bear is famously remembered for being recognized as “a man;” this is the first time in U.S. history that Natives were recognized as human. The events and characters surrounding the Standing Bear story usher in the lengthy struggle all Native Americans faced in achieving their civil rights. Some of the most basic U.S. civil rights, or liberties, are the right to hold property, vote, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, all of which are granted through citizenry. It will take nearly 50 years from the time of Standing Bears’ trial, and gallons of blood, sweat, and tears, before Native Americans are granted these foundational civil rights.

In the year following the Standing Bear victory, many of the same players returned to the district courts in Omaha, Nebraska, seeking to build on the court’s earlier decision. Once again, attorneys Poppleton and Webster, who represented Standing Bear, appeared before District Court Judge Dundy to plead on behalf of Native rights. Poppleton and Webster had asked Dundy in the Standing Bear trial to determine if Native Americans could be considered U.S. citizens; however, Dundy had determined that for the purpose of Habeas Corpus citizenry was beyond the scope of that trial. The issue of citizenship is revisited when John Elk, a Native American living and working in Omaha, is refused the right to register to vote in local elections.

John Elk’s case cannot be decided in District Court so a final decision is handed down by the U.S. Supreme Court four years after the trial began. Poppleton and Webster argue that Elk is a citizen because he was born in the contiguous U.S., and furthermore, that he had surrendered himself to the jurisdiction of the U.S. government. The Supreme Court, in a 7-2 vote, determined that Elk’s surrender to the U.S. had not been recognized by the government, and that his tribal affiliations superseded any allegiance to the U.S.

History has an odd way of remembering events - not all of the players are recalled equally. Standing Bear’s stepping stone victory has cemented his place in history, while the hard fought legal battle of Elk V. Wilkins struggles to be remembered. Similarly, the wife and husband duo of Susette La Flesche and T.H. Tibbles are not remembered equally. The stories of both legal battles and the activism of La Flesche and Tibbles contain lessons that remain relevant to the ongoing struggle for justice and equality today. Their stories teach us the importance of qualities such as knowing one's identity, persevering in the face of adversity, and refusing to accept mainstream intolerance. Revealing the invisible histories of these individuals reminds us of the difference one person can make if they are willing to push against the current.

2014 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"I enjoyed interviewing Susette La Flesche Tibbles' great nieces, Suzette Freivogel and Carolyn Johnson, because it was good to learn about Omaha’s Native American history through her family."

- Domonique B.

"I’ve learned how to be more social and I’ve also learned about Susette La Flesche Tibbles. She was the eldest daughter of the last recognized Chief of the Omaha tribe."- Melessa B.

"I thought this program was going to be boring but after I arrived it became fun. I used to think that Native Americans were not important but then I found out that they had a big part in our history."- Shater H.

Research compiled by Domonique B., Melessa B., Shater H.