Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

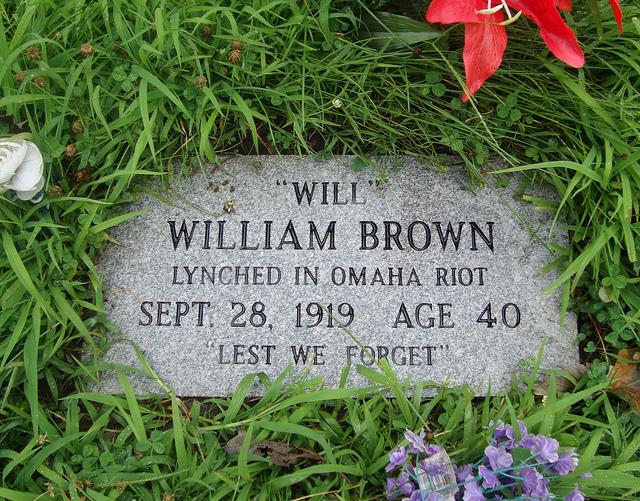

"Lest We Forget"

-

What were the factors that influenced Black migration to Omaha?

Great Migration and Omaha

-

In the early 1900s, African Americans sought a better life in the North. Jim Crow laws in the South reinforced segregation and discrimination. Agricultural problems also made it difficult for African Americans to make a living in the South. African Americans migrated to Omaha seeking better jobs. Labor recruiters, northern newspapers that were sent south, and simple word of mouth helped to keep a steady flow of African American workers coming north during WWI. African Americans often migrated north on trains or buses, traveling with limited possessions, but filled with hope for a better life. African Americans in Omaha settled first in South Omaha for the packing jobs. Then they moved to the Near North Side because of available housing and because they could own their own businesses. North Omaha quickly became the heart of the African American community.

A 5 minute video produced in 2010 interviewing Paulynn Campbell, a lifelong member of Pilgrim Baptist Church. Shared history of the church forming and her African American experience in Omaha.

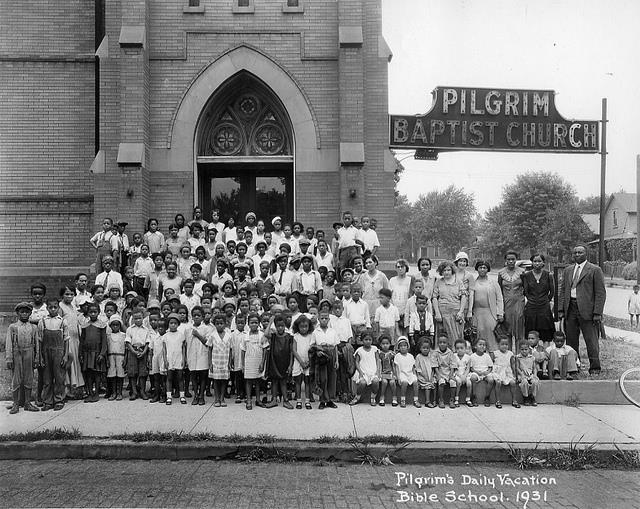

Pilgrim Baptist Church 1931

-

By 1931, Pilgrim Baptist Church was established on the corner of 25th and Hamilton streets in North Omaha. The church, started by migrants from Alabama, was flourishing with members active in developing the North Omaha community and the church itself. The picture shows some members of the congregation participating in Vacation Bible School in 1931. (The Durham Museum Archive Photo)

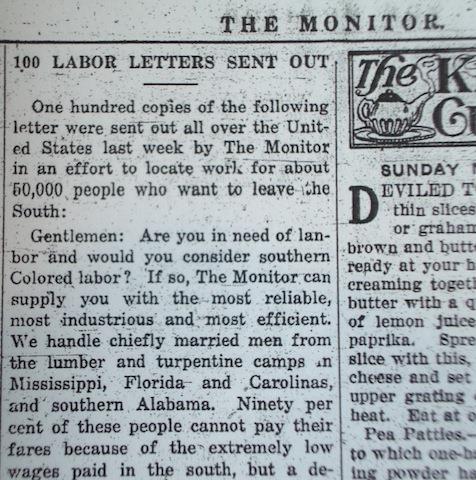

The Monitor as a Recruiter

-

In addition to promoting the African American community in North Omaha, The Monitor served as a recruitment tool to bring southern African Americans north. The Monitor sent copies of their paper to the South at this time to get the message out about what was going on in the North. People came to Omaha to work in packing houses, railroads, and other jobs. (Omaha Monitor Archives)

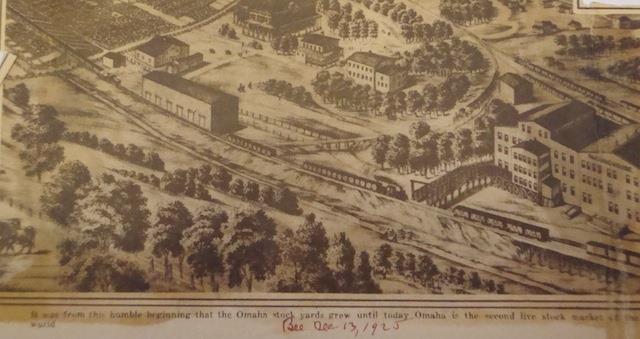

Omaha Employer: the Stockyards

-

During WWI, white men left to fight overseas. Many employers began recruiting southern African Americans to come North to fill the labor void. The primary industries in Omaha that attracted Black workers were the packing houses, railroads, and stockyards. African Americans hoped these new opportunities would provide the basis for a new and better life, away from the Jim Crow South. (Douglas County Historical Society Archives)

Omaha Race Riots of 1919

-

William Brown was a 40-year-old Black man who was wrongly accused of attacking a white woman; this event sparked the Omaha Race Riot of 1919. His grave is at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Potter’s Field. The quote “Lest We Forget” means we should never forget this situation and reminds us that everyone should be treated fairly, regardless of their race.

Additional Information

-

Early leaders helped the community by being the voice for the community. Rev. John Albert Williams was a key leader of the community. He was the first president of the Omaha chapter of the NAACP. Community news events were shared through Black newspapers like The Monitor. Issues of The Monitor were sent to the South to let African Americans know what was going on in Omaha, such as jobs in packing houses and opportunities to own their own homes and businesses.

In 1919, white soldiers who fought in WWI returned to northern cities to find larger African American populations and limited jobs. This led to tension and hostility between Blacks and whites. Newspapers often increased this tension with racist reporting; stories published in the Omaha Bee played a role in instigating the Omaha Race Riot of 1919. In September 1919, Agnes Loebuck and her boyfriend Milton Hoffman told police that on Thursday, September 25, a Black man jumped out, shoved a gun at Hoffman, then raped Agnes. William Brown, was arrested for the attack. Two days later, a mob formed outside the courthouse where Brown was being held. Brown was lynched, hung, shot, dragged through the street, and finally burned. Despite this terrible event, and the reality of discrimination, African Americans continued to define their own lives and create a strong and thriving community. By the 1920s, the African American population in Omaha had grown from roughly 5,000 to 10,000, with almost 70 percent of the population coming from the South.

“The Great Migration,” was the period in which African Americans moved from the South and settled in the North. It was the largest mass migration of any people in American history. From the early 1900s through the 1920s, African Americans migrated to Omaha due to the availability of jobs in the meatpacking industry and the Union Pacific Railroads. The hope of moving north was freedom from discrimination and the chance to gain equal rights. African Americans quickly began making Omaha their home, first settling in South Omaha then moving to North Omaha, along 24th, 30th, Cuming and Lake streets.

Many white business owners left North Omaha, isolating the African American community, and causing Omaha to become segregated. As years went on, redlining, racial covenants, and more race riots in the 1960s reinforced racial segregation in Omaha. What was once a thriving community, North Omaha is still struggling in 2010 to rebuild and recover from years of segregation and racism. But with the spark of new developments such as businesses and housing, North Omaha is hoping to once again become the center of the Black community and an area to which African Americans will migrate back.

2010 MIHV Project

-

"One thing that amazed me was Will Brown's case where everybody had it wrong. Another thing I enjoyed was when we did our interview with Mrs.Campbell; she took us on a tour of the church and showed us the Bible that survived the church fire."

— Micah W.

"I enjoyed learning about the migration to Omaha. In the early 1900s African-Americans first settled in South Omaha for the packing jobs. Then they moved to the North part because of the available housing and because they could own their own businesses."— Domonique J.

"The camp has given me a better understanding of Omaha's history, and Will Brown. I wish this type of history would have been reflected more in elementary & middle school."— Keith M.

Resources

-

Jewell, Jimmy. “Cultivating a Community Dream: The Rich Legacy of African Americans in Omaha.” Dreamland. 1 (2006): 14-17.

Williams, Rev. John Albert. The Monitor. 3 March 1922, 1.

Additional Making Invisible Histories Visible content on the Great Migration:The interactive MIHV "Great Migration" eBook is available for free download from the Nebraska Department of Education website.

Research compiled by: Domonique J., Keith M., Micah W., Lindsay B., and Akia S.