Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

African American Law Enforcement

-

What were some of the key changes that needed to be made in order to integrate the Omaha Police Department?

Police: A Brotherhood of Black and Blue

From the 1960s to Today

-

Sirens, arrests, crime, violence, all lead to one place. These are just a few words that come to mind when one thinks of the police. However, through our research, we learned that the Omaha Police Department is very dedicated to keeping the city of Omaha safe. We also discovered that African American police officers are a very large part of the OPD. They often faced struggles such as racial tensions, discrimination, forced residential assignments, and affirmative action.

Today there is diversity within the Omaha Police Department, thanks to the brave officers who came before and after affirmative action. This paved the way for African American police officers such as Thomas Warren, Mark Foxall, Isaiah Jackson, and Marlin McClarty who changed the force. Thomas Warren stated that “He knows that he (like so many others) wouldn’t have been hired without the lawsuit.” Therefore, this allowed him to “stand on the shoulders of those who had come before him,” but also, like Mark Foxall and Marlin McClarty gave them a chance to blaze their own trail and make their mark in the Omaha community.

A 10 minute video produced in 2012 interviewing Isaiah Jackson, Marlin McClarty, Thomas Warren and Mark Foxall.

Omaha Police Department in the 1960s

Police During the Civil Rights Era

-

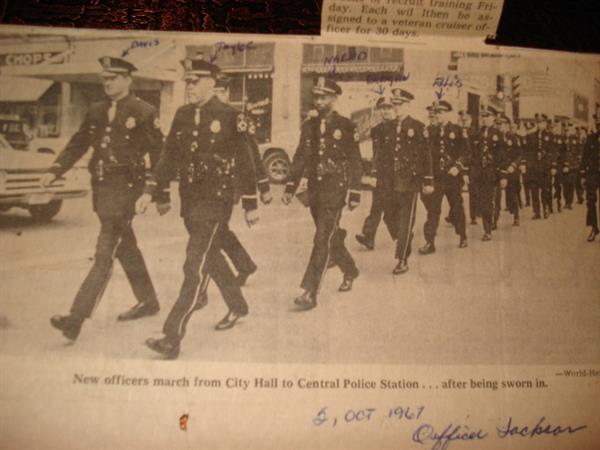

The Omaha Police Department in the 1960s was a difficult place to work if you were a Black person because there were only 15 to 25 Black police officers in the department. The 1960s was a turbulent time for Black individuals as many were seeking equal employment opportunities. Isaiah Jackson, a retired Black Omaha police officer, explained that when he decided to join the force in 1967, some of his friends did not agree with his decision. A police captain told Jackson, “Your real friends will give you a hug and those are your true friends.” Jackson shared a story that, as a young officer in 1969, George Wallace came through Omaha on his presidential campaign and a civil disturbance broke out between the Blacks and whites in attendance. Jackson also shared his personal experiences and the changes that he saw take place during his career in the department. The significance of the employment of Black officers in the 1960s was that it paved the way for the future development of the Brotherhood of Midwest Guardians, but fell short of proportional Black representation on the force until later lawsuits. (Photo courtesy of Isaiah Jackson).

The Brotherhood of the Mid-West Guardians

-

In the late 1970s, Black police officers remained a small proportion and these officers felt they were not being represented by the predominantly white Police Union. Black police officers responded by establishing The Brotherhood of the Mid-West Guardians in Omaha. This organization was the voice of Black police officers in the department. In 1979, Black policemen sued the city of Omaha for $10 million. As a result of this lawsuit, the city made changes to its hiring policies. The next year, a consent degree was included in an affirmative action plan which forced the city to hire more African American officers. The law stated that 40 percent of newly hired officers had to be African American until the Police Department reached a goal of 9.5 percent. This decree also required the city to look into the promotional practices to ensure African American officers were represented in the supervisory ranks. (Photo courtesy of Marlin McClarty)

Brotherhood: Influential Leaders

-

Thomas Warren, Mark Foxall, Isaiah Jackson, and Marlin McClarty all have one thing in common: throughout their careers as police officers and beyond, they have been committed to serving the citizens of Omaha, Nebraska. In the 1960s, it was uncommon to see an African American police officer in Omaha. During that period, Isaiah Jackson served as one of the few Black patrolmen on the force. In early March 1968, segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace came to Omaha to campaign for president. The controversial governor's visit attracted tense protests and prompted a mini-riot. Police officers, including Jackson, were called in to stop the violence, a tricky assignment given the racial politics on the force and in the community at that time. Thomas Warren joined the force in 1983 after important departmental changes brought by affirmative action. Following a historical legal case, the Omaha Police Department was forced to seek out and hire more Black officers. Reflecting on this turbulent time of change in the force, Warren felt the new policy, while needed, also strained race relations because many whites believed African Americans had received preferential treatment. Despite these internal tensions, Warren worked his way through the system, eventually becoming the first Black Police Chief in the history of the Omaha Police Department. Mark Foxall comes from a long, rich family history of law enforcement. He followed in the footsteps of his great-uncle, who served during the 1930s, and his father, the late Police Captain Pitmon Foxall, who faced a variety of racial challenges on the force in the 1950s and 1960s. Mark and his brother, who came on to the force during the 1980s, also faced discrimination during that era, but it did not discourage Mark. Instead, he stayed persistent and later became a Police Sergeant. In 2012, he was the director of the Douglas County Department of Corrections. Marlin McClarty also had a family history in law enforcement. His father is a retired Sergeant, Marvin McClarty. Marlin's role as president of The Brotherhood of the Mid-West Guardians, which is the Black officers' union, has played a major part in the hiring and promotion of qualified Black police officers. Because of the efforts of the Brotherhood of the Mid-West Guardians, these pioneering Black policemen, and ongoing efforts at recruitment, in 2012 there are more than 75 African American officers in the department.

Additional Information

-

In the 1960s, tensions were high between the African American community of North Omaha and the Omaha Police Department (OPD) after the killing of a young girl named Vivian Strong. Her death led to riots and rebellions as well as the hiring of more Black officers in the OPD.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the OPD did not push as hard for more Black officers as they did in the immediate aftermath of the 1960’s riots and the number of African American recruits soon dropped. African Americans had limited access to jobs on the police force as a result of the OPD’s hiring practices and were constrained within the department by the OPD’s job assignments, restrictions on moving into other units, and lack of promotional opportunities.

In November of 1986, efforts to recruit Black officers increased again due to a lawsuit filed by the Brotherhood of Midwest Guardians. These officers were the first class to be hired under the new consent decree. Though this decree was a victory for Black officers, they still had not won the battle. The department did lower its threshold on test scores in order to create a more diverse pool (with regard to both race and gender) but argued that the difference in test scores was small and made little substantive difference.

After that, the OPD continued to hire more and more Black officers each year. In 2003, the department appointed its first Black Police Chief, Thomas Warren. In 2012, there were more than 75 African Americans on the police force. The OPD has made some great advances toward establishing equality and justice not only for the citizens within the community but also for those who decide to join the force.

2012 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"Through the duration of this program, I was blessed with the opportunity to really understand the importance of North Omaha's black history and how significant it is to the community today. With the experiences that I've had I truly feel like I will walk out of this program a changed person, in terms of knowledge, views, and processing thoughts about the community."

- Joy K.

"I think this program is significant because I learned you don't judge a book by its cover in other words you don't judge North Omaha until you find out the hidden history behind it. That's why this program is so important to me because they let you know life lessons and this program I'll remember for life because it taught me about my own history and ancestors. It also taught me about my community and African American communities."- Tre'Vonte J.

"This presentation is significant because this will be an easy tool for people who want to learn about the police force if you want to read along and watch a video. It informs people about affirmative action, the hard times of the 1960s, and the struggles of their past through their own voice, their own eyes. It was an honor meeting them and listening to their stories. I met some awesome people, I learned how to write better than I did, and most importantly, I gained a respect for African American history. And for that, I thank Making Invisible Histories Visible."- Seth F.

Resources

-

Oral Histories

Foxall, Mark. Interview by Tre'Vonte J. Omaha, NE. July 17, 2012.

McClarty, Marlin. Interview by Joy F. Omaha, NE. July 18, 2012.

Jackson, Isaiah. Interview by Seth F. Omaha, NE. July 17, 2012.

Warren, Thomas. Interview by Joy F. Omaha, NE. July 17, 2012.Articles

Fogarty, James. "Black Policemen Are Needed 'It's Not like Joining the Enemy.'"

Omaha World-Herald, January 28, 1973.

Hyland, Terry, and Rich Janda. "Detail Shift, Promotions Give Police a New Look." Omaha World-Herald, September 4, 1986.

"Fire, Police Plan Training."Omaha World-Herald, February 6, 1981.

"Police Cars Integrated."Omaha World-Herald, July 12, 1963.Special Thanks

Isaiah Jackson

Thomas Warren

Mark Foxall

Research Complied by: Seth F., Joy K., Tre'Vonte J., Bill K., and Akia S.