Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

African American Educators & Education

-

What were the different ways in which African Americans worked to improve education in Omaha?

"Work Hard and Do the Best You Can Do"

Education in Omaha

-

African Americans have faced numerous obstacles over the years, including several within the field of education. From segregation to unfair hiring practices, to outdated textbooks, to dilapidated buildings, African Americans are still persevering. African American parents realized that their children were not receiving an equal education and decided to take legal action against the Omaha Public Schools district in the hopes of having a more integrated educational system. The courts intervened to assist in the desegregation of Omaha Public Schools. Eventually, mandatory busing was put into place, essentially integrating the district in the 1970s. In 1999, the Omaha Public School district ended mandatory busing. Students could then choose to go to any school they wanted, but most chose their neighborhood schools. Due to the issues surrounding redlining, the practice of steering members of certain racial groups to live in certain areas of the city, race-based neighborhoods are causing the classroom images of segregation from the past to slowly creep back into some schools.

A 4:28 Video Interview in 2010 with Omaha Public School educator Thomas Harvey. Also interviewed Felicia Dailey with the UNO Black Studies program about how UNO’s Black Studies program started in 1971.

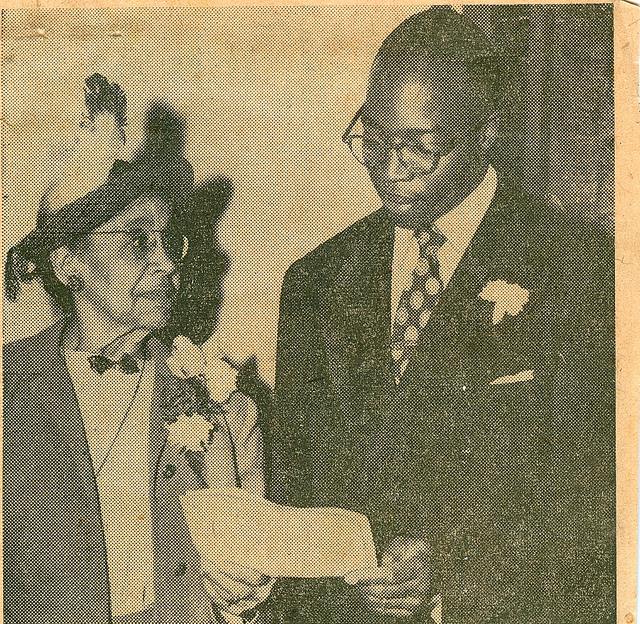

Lucinda Gamble (Mrs. John Williams) and Dr. Eugene Skinner

-

In 1895, Lucinda Gamble (later Mrs. John Williams) was hired as the first African American teacher in the Omaha Public Schools.

The hiring of African American teachers continued to be a rare occurrence over the next 50 years. In the 1960s, Omaha’s school district reached a turning point, and the hiring of African American teachers started to become more fair and frequent, although improvements in hiring practices can still be made today.

There have been many African American teachers in Omaha schools that have made a significant impact on the community. One of these educators who paved the way for future African American educators was Dr. Eugene Skinner. Dr. Skinner was first hired as a full-time teacher in the Omaha school district in 1940. He was the first African American: principal of an Omaha school in 1947; principal of an Omaha Jr. High school in 1965; administrator in the Omaha school district in 1968; and assistant superintendent in 1969.

Busing Changes The Omaha Public Schools

-

While laws did not mandate segregated education in the North as they had in the South, housing patterns and numerous decisions by policy-makers nonetheless resulted in the de facto segregation of Omaha schools.

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that federal courts could order busing to integrate public schools, and in 1976, a federal court order mandated busing in the Omaha Public School system. The decision increased racial tension in the city, causing some white Omaha residents, who wanted to block the new busing policy, to raise money and distribute "no busing" bumper stickers in protest. During this period, white student enrollment in OPS decreased dramatically, placing the majority of the busing burden on African American students who were encouraged to travel, often long distances, to predominantly white schools.

Mandatory busing in Omaha ended in 1999 when the district adopted an open enrollment policy based on income instead of race. Yet, evidence of re-segregation in the early 2000s prompted a controversial new plan creating three distinct learning communities controlled by Omaha neighborhoods organized largely around patterns of race and ethnicity. Race and education policy continue to be hotly debated in Omaha to this day.

Pamphlet Describing Desegregation Plan 1977-1978

-

On Jan. 1, 1976, the OPS Board of Education presented a plan to the Federal District Court for student desegregation that was scheduled to begin in the fall of the 1976 school year. Prior to making this court-ordered presentation, members of the Omaha community were given an opportunity to express their views through several town meetings. Suggestions were received and studied by the Board and the school-appointed Integration Task Force. In an attempt to answer the many questions that were posed, pamphlets and materials such as “The Plan” (pictured) and other brochures were made available to explain the major change in educational policy. Formulated in response to a report from the Omaha Community Committee, "The Plan" specified how the Omaha Public Schools could begin to take steps to integrate its public schools.

On Jan. 1, 1976, the OPS Board of Education presented a plan to the Federal District Court for student desegregation that was scheduled to begin in the fall of the 1976 school year. Prior to making this court-ordered presentation, members of the Omaha community were given an opportunity to express their views through several town meetings. Suggestions were received and studied by the Board and the school-appointed Integration Task Force. In an attempt to answer the many questions that were posed, pamphlets and materials such as “The Plan” (pictured) and other brochures were made available to explain the major change in educational policy. Formulated in response to a report from the Omaha Community Committee, "The Plan" specified how the Omaha Public Schools could begin to take steps to integrate its public schools.Evidence of re-segregation began to emerge in some Omaha schools in the early 2000s, prompting a controversial new plan creating three distinct learning communities. The communities would be controlled by Omaha neighborhoods organized largely around patterns of race and ethnicity. Race and education policy continue to be hotly debated in Omaha to this day. (Photo courtesy of Omaha Public Schools).

Additional Information

-

This page gives an overview of some struggles African Americans faced in the area of education. The 9th grade students who worked on this page decided that the primary issues in education impacting the lives of African Americans in Omaha were desegregation, busing, and the hiring practices of African American teachers. Through this experience, students were able to gain a better understanding of the history behind their school system. Students also came away with a greater appreciation for the significance of history and how the actions of the past can impact their lives.

The student-conducted interview with Thomas Harvey, featured in the video posted above, gave students a first-hand account of how African American teachers and students in North Omaha struggled for equality. Harvey also explained how he worked to increase enrollment of schools in the Black community by creating magnet programs in areas like technology, math, science, and engineering.

To further expand on how African Americans impacted education in Omaha, students visited the University of Nebraska at Omaha. There they met with Felicia Dailey, an administrative assistant in the Black Studies Department. Dailey shared how the department was started through the actions of African-American students who felt that there was a need for a Black Studies department in 1971. UNO is currently one of a limited number of universities in the country that offers a Bachelor of Arts in Black Studies. Dailey also stressed the power of students’ voices and participation in the efforts to change things for the better.

Student Reflections

-

"What I learned about the education project is how segregation was a big problem and how Omaha public schools treated teachers by the way they looked."

- LaShaye

"My brain is stuffed with fascinating information. This camp has taught me to fight for what I believe in, and to stand up for my rights."- Shayla

"I learned a lot of interesting information about Omaha’s African American history, especially in the area of education. I found the story that explained how schools were segregated and eventually integrated the most interesting."- Moises

Resources

-

Omaha Public Schools

3215 Cuming Street

Omaha, NE 68131

(531) 299-0220

Douglas County Historical Society

5730 North 30th Street

Omaha, NE 68111-1600

(402) 455-9990

Research Compiled by: Shayla S., LaShaye BC, and Moises D.