Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

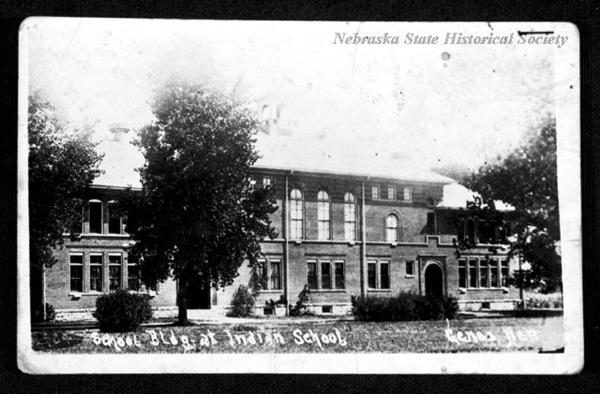

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

The Omaha Native Indian Tribe

-

How has the Omaha tribe adapted to changing circumstances since the founding of the city of Omaha?

Omaha: The Foundation, The Tribe, The City

-

The city of Omaha is known for many things, including meat packing, the Union Pacific railroad, and attractions like the Henry Doorly Zoo and Werner Park. However, many people do not know that the city is named after the Omaha Native American Indian tribe. Omaha means, “to go against the current,” and the tribe was given this name because they went upriver and migrated to the Nebraska Territory. In the 1700s, the Omaha tribe settled along the Missouri River and lived there until the Civil War era, when white American settlers began moving into the area. In 1854, the Omaha tribe ceded their land and moved to a reservation that is located in present day Macy, Nebraska. Once the U.S. government controlled this land, the city of Omaha was founded. However, this did not mean that the tribe disappeared. They continued to adapt to life on the reservation, and by the 20th century, many had moved back to the city of Omaha. In this project, you will learn about the Omaha tribe’s ongoing legacy to better understand the people that our city is named after.

The city of Omaha is known for many things, including meat packing, the Union Pacific railroad, and attractions like the Henry Doorly Zoo and Werner Park. However, many people do not know that the city is named after the Omaha Native American Indian tribe. Omaha means, “to go against the current,” and the tribe was given this name because they went upriver and migrated to the Nebraska Territory. In the 1700s, the Omaha tribe settled along the Missouri River and lived there until the Civil War era, when white American settlers began moving into the area. In 1854, the Omaha tribe ceded their land and moved to a reservation that is located in present day Macy, Nebraska. Once the U.S. government controlled this land, the city of Omaha was founded. However, this did not mean that the tribe disappeared. They continued to adapt to life on the reservation, and by the 20th century, many had moved back to the city of Omaha. In this project, you will learn about the Omaha tribe’s ongoing legacy to better understand the people that our city is named after.Published on Jul 22, 2016

Students interviewed Eduardo Zendejas, a UNO professor and member of the Omaha tribe, and they created this documentary as part of the Omaha Public Schools Making Invisible Histories Visible initiative.

Early Settlement

-

The Omaha tribe originally lived in the Ohio River Valley. In the 17th century, other tribes located as far as the east coast of the United States began moving into this area as well. The tribal group that eventually became the Omaha responded by migrating west, ultimately reaching the Mississippi River. Here, half of the tribe decided to go south, while the other half decided to go forward and upstream. This group became known as the Omaha, meaning “going against the current.”

As the tribe continued to move west, they eventually crossed the Missouri River, creating a settlement near Sioux City, South Dakota, and named their new territory “Big Village.” However, the Sioux Tribe already lived in this area, and disliked the Omaha—particularly because they were in competition for buffalo during the hunting season. Buffalo were extremely important to Native American tribes, as they used the animal for food, shelter, clothing, weapons, and other tools.

The Omaha migrated south out of the Sioux territory, and entered present-day Omaha, near what is now Fontenelle Forest. This area became their permanent home, and they began building earth lodges. The depressions from these dwellings can still be seen in 2016 in the forest, like the image shows. In addition, the tribe started a fur trade with the French and continued trading with white settlers. The Missouri River became a valuable resource for trade, and allowed the tribe to farm crops like corn. The Omaha tribe stayed in the area until 1854, when the U.S. government sent them to a reservation.

An earth lodge depression in Fontenelle Forest.

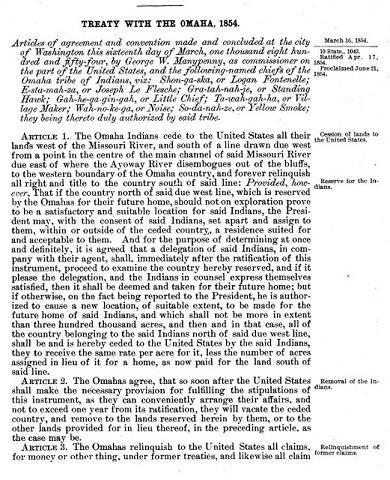

The Treaty of 1854

-

After settling and living in what is now the Fontenelle Forest area for many decades, the Omaha Tribe encountered difficulties. They were still having conflicts with the Sioux, but now the U.S. government wanted the Omaha’s territory to continue expanding westward. The Omaha were faced with the option of leaving their lands or making war with white American settlers.

After settling and living in what is now the Fontenelle Forest area for many decades, the Omaha Tribe encountered difficulties. They were still having conflicts with the Sioux, but now the U.S. government wanted the Omaha’s territory to continue expanding westward. The Omaha were faced with the option of leaving their lands or making war with white American settlers.After much debate, they decided to negotiate with the United States, leading to The Treaty of 1854. As part of the treaty, the Omaha agreed to cede their land to the U.S. government and move to a reservation near what is now Macy, Nebraska. The fact that they could stay in the Nebraska Territory was significant to the Omaha tribe because, at this same time, many tribes were being forced to move away from their homes and onto reservations in the Indian Territory, or modern-day Oklahoma. Other terms of the Treaty of 1854 specified that the tribe had to use all the reservation land or the government would take it back. They also could not leave the reservation and were not allowed to make war with other Native American tribes or white American residents who were encroaching on the area.

As the tribe moved to their new reservation and the Treaty of 1854 was ratified, a man named Jesse Lowe used his ferry company to help establish a city on the west side of the Missouri River, which became Omaha, Nebraska. Jesse Lowe decided to name the city after the tribe because the Omaha had owned the land before the Treaty of 1854. While choosing to name the city after the tribe may seem to honor the Omaha, it does not expose the forced removal of the tribe to a reservation and the many challenges they would face in the years to come.

Urban Indian Experiences

-

Once tribes across the country were forcibly removed onto reservations, the U.S. government implemented several policies that attempted to assimilate Native Americans into white U.S. culture. Boarding schools, like the Carlisle School in Pennsylvania and the Genoa Indian School in Genoa, Nebraska, were created. By the mid-20th century, Native Americans were encouraged to leave their reservation for a larger city through the Voluntary Relocation Program in 1952. With this program, many people from the Omaha tribe moved from Macy to the city of Omaha.

The relocation program was responsible for the movement of more than 30,000 Native Americans all around the country. Those who moved became known as urban Indians. Many people partook in the program because of the incentives it promised. The U.S. government was supposed to provide a house for a family unit and $80 a week for four weeks. Despite these benefits, many urban Indians struggled with the assimilation process, felt homesick and, ultimately, moved back to their reservations.

The land near Creighton University in North Omaha, close to where Interstate 480 is located today, was one of the neighborhoods where many of the Omaha tribe moved during this relocation era. This area was called Jefferson Square and can be seen in the photo. The expansion of Creighton University during the 1960s slowly took over this neighborhood and forced the Native American community to continuously move around Omaha looking for new homes. This kind of dislocation was common for many urban Indian communities around the country. In 2016, the Omaha are settled in many areas across Nebraska, including the reservation near Macy, Nebraska, and the city of Omaha.

Being uprooted so often made it difficult for many Native Americans to build communities in cities. However, many still try to bring people together by creating centers and organizations for urban Indians. In 1987, students at the University of Nebraska at Omaha revived American Indians United to build relationships among Native students and to teach young Natives to be proud of their heritage. (Courtesy of Archives & Special Collections, Criss Library, University of Nebraska at Omaha. The Gateway Newspaper Archive)

Being uprooted so often made it difficult for many Native Americans to build communities in cities. However, many still try to bring people together by creating centers and organizations for urban Indians. In 1987, students at the University of Nebraska at Omaha revived American Indians United to build relationships among Native students and to teach young Natives to be proud of their heritage. (Courtesy of Archives & Special Collections, Criss Library, University of Nebraska at Omaha. The Gateway Newspaper Archive)2016 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

"What I liked about MIHV is mainly learning about the past of my surroundings. Now, I don’t just see normal streets and old buildings, but a historic community growing with success."

- Jocabed C.

"I liked how everyone in the program was welcoming and kind. We all supported each other, and I liked that. If I could do this again I would. It was fun and just a good experience."- Trinity W.

"I really enjoyed the food and education. The teachers really put us to work and made it seem like an actual job. They were very supportive, which helped us create a great project."- Deven W.

Research compiled by Deven W., Jocabed C., & Trinity W.

Deven W., Jacobed C., & Trinity W. This fall Jacobed will be attending Bryan High School while Trinity and Deven will attend Burke High School. These three 9th graders enjoy history and have a love of food and music.