Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Preserving Native American Tradition

-

How are Indigenous perspectives of Native American arts and powwows different from the observations of outsiders?

How can these misunderstandings be avoided?

Preserving Tradition for the Future

-

Left: "Indian Dancer, Macy, Nebraska" 1922 (Courtesy of Nebraska State Historical Society).

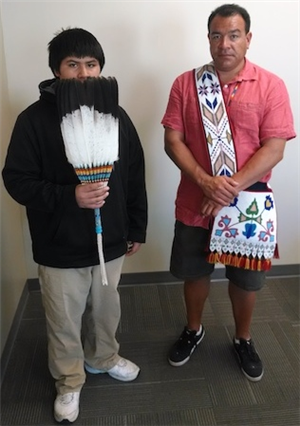

Right: Taylor Keen and Mariano M. July 14, 2014. Notice the similarity between the prayer fan in this photo and the 1922 photo.

Arts and Culture

-

Omaha… Ponca… Pawnee… Winnebago… Native. Each tribe has its own unique culture, but they also share a pan-Indian identity. Before the civil rights era of the 1960s, Native Americans tended to identify only with their tribal communities. During the civil rights era, a pan-Indian rights movement began, which was called the Red Power movement. The Red Power movement was influenced by earlier civil rights groups like the Black Panther Party. This movement created a new Native identity that crossed tribal lines. With this new identity came a renewed sense of cultural pride among Native peoples, and they began to practice their traditions and beliefs more publicly. By doing this, they defied problematic stereotypes that Euro-Americans had created, and Native Americans pushed back against the cultural suppression that had occurred during the late 19th through the early 20th centuries.

This breakthrough for Native Americans inspired many of them to revitalize their arts and culture. As they revitalized their traditional cultures, some made changes to their traditions that were influenced by modern American culture, often adding to the many older traditions they already had. These mixed cultural traditions reflect the multiple cultural identities that many Native Americans experience. These multi-cultural identities were forced on Native peoples during the assimilation era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During this assimilation effort, Native Americans felt connections to both their tribal cultures as well as the Euro-American culture they were being taught. However, Native Americans of today are choosing how to bring these cultures together instead of being told how to do this by Euro-Americans. Native Americans and their cultures were mistreated by the Euro-Americans, but now they are trying to overcome oppression.

One of the aspects of Native American culture that experienced a resurgence as a result of the Red Power movement is the powwow. Powwows used to be celebrated by individual tribes, but now there are many inter-tribal powwows that host dancers from tribes that come from across the country. The traditional dance and the fancy dance are examples of how powwows have changed since the Red Power movement, since each tribe has its own version of the traditional dance, but the fancy dance is more similar between different tribes. There are many ceremonial artifacts that are used in powwows as well. Some sound like everyday objects, like the fan and the shawl, but they are, in fact, traditional pieces of Native art that have specific meanings when used in a powwow. There are also many historical places that are closer to you than you might think. If you look hard enough, you may even find that one of your favorite hangouts is full of history!

Throughout the webpage, I learn about Turner Park and its significance to this local cultural renewal, traditional Native American music and how it is modernized today, and traditional ceremonial artifacts and symbolism used in powwows. Make sure to also check out an interview with Octa Keen, an elder in the Omaha tribe, and her son, Taylor Keen, to learn about how modern Native Americans in the Omaha community practice their traditions.

A 6 minute video interview done in 2014 with Octa Keen, an elder in the Omaha tribe, and her son, Taylor Keen, talking about Pow Wows and why it was important for Octa to have her children participate in learning Native American culture, even though the outfits are expensive to make. Show samples of different Pow Wow outfits. Taylor believes it is a privilege to dance in the circle and one day he would love to see an Indian Interpretive Center where the Native Indian culture can be shared and passed on.

A Place to Remember History

-

This is an image of Turner Park on the 31st to 33rd blocks of Dodge in Midtown Omaha. In the 1800s, Turner Park was in the area where the Omaha tribe lived. Today, it is used for concerts and a green space. The park is in the shape of the camps that the Omaha people stayed in when they lived there. Recently, the Omaha tribe had a powwow in Turner Park in order to remember a place that was theirs long ago. People walk and drive by this location thinking that it is only a park, but it is not. It is a place that’s important to the Omaha tribe’s culture.

This is an image of Turner Park on the 31st to 33rd blocks of Dodge in Midtown Omaha. In the 1800s, Turner Park was in the area where the Omaha tribe lived. Today, it is used for concerts and a green space. The park is in the shape of the camps that the Omaha people stayed in when they lived there. Recently, the Omaha tribe had a powwow in Turner Park in order to remember a place that was theirs long ago. People walk and drive by this location thinking that it is only a park, but it is not. It is a place that’s important to the Omaha tribe’s culture.

Representation and Resistance

-

Non-Natives’ understandings of Native American music have greatly changed over the years. Euro-Americans’ attempts to compose music that described the culture of Native Americans usually ignored traditional references such as the heart-beat drum rhythm found in traditional songs and dances. Despite non-Native composers’ attempts to introduce other cultural music to mainstream society, music has misrepresented the original Native American arts.

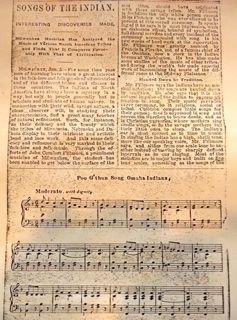

Euro-Americans began imitating Native American music around the era of Native American Removal and Pacification. An article (pictured above) from February 1895 reports on Milwaukee musician John Comfort Fillmore, who composed a series of Omaha tribal songs. Fillmore attended a traditional powwow, listening to the music, and later transcribed what he heard onto sheet music, claiming it to be “entirely uninfluenced by contact with civilization.” The article continues, describing Native Americans as “wild and savage in nature.” Fillmore explains that Native American music and singing include melodies in major keys and are built on five-tone scales similar to those used by the ancient Chinese, Hindu, Scotch, Irish and other cultures. Fillmore also claims that Native Americans had no musical notation. While Fillmore correctly states that the Natives did not use harmonization as Western musicians did in their songs, his other observations show a lack of cultural understanding.

Euro-Americans began imitating Native American music around the era of Native American Removal and Pacification. An article (pictured above) from February 1895 reports on Milwaukee musician John Comfort Fillmore, who composed a series of Omaha tribal songs. Fillmore attended a traditional powwow, listening to the music, and later transcribed what he heard onto sheet music, claiming it to be “entirely uninfluenced by contact with civilization.” The article continues, describing Native Americans as “wild and savage in nature.” Fillmore explains that Native American music and singing include melodies in major keys and are built on five-tone scales similar to those used by the ancient Chinese, Hindu, Scotch, Irish and other cultures. Fillmore also claims that Native Americans had no musical notation. While Fillmore correctly states that the Natives did not use harmonization as Western musicians did in their songs, his other observations show a lack of cultural understanding.Fillmore is only one example of the many false representations of Native American music. However, Native American artists, particularly younger musicians, have pushed back against these types of misrepresentations. For example, the group A Tribe Called Red combines traditional Native American music with elements of electronica and hip-hop. (View a YouTube video of the group’s song “Electric Pow Wow Drum”) This shows Native American agency in bringing tribal music into the modern context of Western society, demonstrating cultural pride and revitalization, as well as the ongoing theme of inter-cultural exchange. Unlike the Fillmore example, where a non-Native forced the Omaha music into Western forms, this trio chooses for themselves the terms of that cultural exchange.

Arts and Modern Powwows

-

Present-day singing and dancing in a traditional Native American powwow are based on the tribal circle framework. The singers and dancers do not refer to themselves as “artists” and/or “performers,” as Euro-American artists would. Rather, their participation is part of their identity as a tribe, family, or clan. Songs and dances are passed down from each generation, sometimes skipping generations. Emotion is emphasized in drum group singing by maintaining drumbeats and by the type of song.

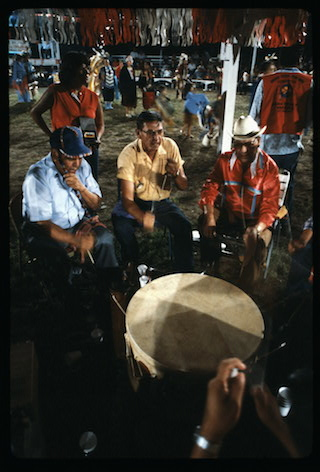

Present-day singing and dancing in a traditional Native American powwow are based on the tribal circle framework. The singers and dancers do not refer to themselves as “artists” and/or “performers,” as Euro-American artists would. Rather, their participation is part of their identity as a tribe, family, or clan. Songs and dances are passed down from each generation, sometimes skipping generations. Emotion is emphasized in drum group singing by maintaining drumbeats and by the type of song.Powwows revolve around the drum. It is considered to be living and breathing with a spirit. It has its own ceremonies with blessings and namings and symbolizes a heartbeat and life-giving thunder. Women are not allowed to drum. The traditional drum is made out of deer, elk or horsehide material. Contemporary bass drums may be purchased, renovated, or blessed. The heartbeat starts out slowly then accelerates as singers go further into song. The drum sticks connect singers to the power of drums as they sing. The host drum (pictured) is an invited drum group and is called upon for special songs for families and honoring important people.

Some songs used in powwows are the Flag Song, the Honor Song, and the Trick Song. The Flag Song honors the flag of the United States. The Honor Song is requested to honor someone. The Trick Song is a contest between the dancers and singers, with drummers trying to fool the dancers.

Attending a powwow is the best way to experience Native American music today. Misinterpretations like Fillmore’s (See above entry) can be avoided by careful observation and interviewing powwow participants, which in the end helps Native American cultural revitalization.

Symbols and Regalia

-

Native American art and culture includes complicated symbolism. This symbolism is best seen and experienced at powwows. Regalia is the term used to describe clothing, accessories, shawls, blankets, and other items that are used in ceremonies and at powwows.

Native American art and culture includes complicated symbolism. This symbolism is best seen and experienced at powwows. Regalia is the term used to describe clothing, accessories, shawls, blankets, and other items that are used in ceremonies and at powwows.Different colors and symbols appear on Native American regalia, but each tribe has its own meaning for the symbols and colors. For example, the prayer fan belonging to Taylor Keen, a member of the Omaha tribe, (pictured here) has a rainbow design on the handle. Taylor explains that the colors represent fire or no more flooding. This was from when God had flooded the earth. The eagle feathers are used because, according to Omaha beliefs, the eagle is one of the most powerful animals. This fan is used at ceremonies to send prayers to God. The water bird and the thunderbird are also common strong spiritual symbols. Some regalia represents the mixing of two cultures: Euro-American and Native American. This can be seen by the crosses that represent Christianity on both the skirt and the fan. Christianity, which has become part of many Native Americans’ religious beliefs, is sometimes mixed with traditional tribal religion.

Many young people today like to use bright colors for their regalia. This skirt is like many other types of regalia: the colors are usually dark on light or light on dark. The skirt was made about 10 years ago and still looks new. These skirts are only used at ceremonies. Octa Keen, Taylor’s mother, said that some people say that she should sew skirts like this by hand and not with a machine, but she thinks if the older Native women could have used the machine, they would have. Octa also uses old photographs of tribal members dressed in regalia that she has found on the internet to help her make regalia that is based on older patterns and styles. This is important because it shows how much the culture has adapted to changes in technology.

Additional Information

-

Like many tribes across the country, the Omaha tribe has recently experienced a resurgence of cultural pride and a renewed effort to restore traditional practices, especially among younger generations of tribal members. This revitalization stemmed from the Red Power movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Reacting against the policies that the U.S. government implemented in an attempt to eradicate Native cultures, Red Power activists embraced a militant form of activism in order to defend Native rights and advocate for a broad range of Indian interests. The movement also promoted a more public display of Native cultural pride, which encouraged many Native Americans to revitalize cultural practices that had been forcibly suppressed.

Numerous factors complicate contemporary cultural revitalization, including the assimilation policies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During this era, many Native Americans adopted aspects of American culture, so contemporary Native peoples are presented with the need to adapt their tribal traditions to better reflect their multi-cultural identities. However, a spectrum of perspectives exists among Native Americans regarding whether or not contemporary American culture should be included in traditional practices.

As the students’ work suggests, modern cultural revitalization among Native American tribes embodies a shifting power dynamic in the American-Native cultural exchange, an exchange which historically has been controlled by white Americans. By restoring tradition while remaining flexible to contemporary American influences, current Native Americans assert agency and demonstrate the vitality of their cultural traditions.

2014 MIHV Project

Student Reflections

-

“Making Invisible Histories Visible not only educates people on other cultures but also helps people understand and embrace cultural differences.”

- Jenna R.

“At first I thought this was going to be boring, but I thought it was awesome because I learned a new type of music, got to travel, and met new people.”- Mariano M.

“The best part of this experience has been being a part of a group who is helping people learn about a new culture and what they went through over the past hundreds of years.”- Shylene C.

Resources

-

DesJarlait, Robert. “The Contest Powwow versus the Tradition Powwow and the Role of the Native American Community.” Wicazo Sa Review 12, no. 1 (Spring, 1997): 115-127.

Douglas County Historical Society. www.omahahistory.org/

Farrell, Michael. “Dancing to Give Thanks.” Nebraska Public Television. February 25, 1988. www.netnebraska.org/interactive-multimedia/culture/dancing-give-thanks (accessed July 15, 2014).

Jordan, Steve. “Midtown Crossing Dedication—Tribal Village Inspired Architect on Project.” Omaha World-Herald. May 18, 2010.

Library of Congress. “Omaha Indian Music Collection.” www.loc.gov/collections/omaha-indian-music/about-this-collection/#overview (accessed July 9, 2014).

Medicine, Bea. “Native American Resistance to Integration: Contemporary Confrontations and Religious Revitalization.” Plains Anthropologist 26, no. 94, Part 1 (November, 1981): 277-286.

Sans Souci, Renee. “The Nebraska Educator’s Guide to American Indian Singing and Dancing.” The Ixtlan Education Group. www.liedcenter.org/sites/default/files/documents/NE_Educators_Guide-2.pdf (accessed July 10, 2014).

St. Joseph’s Indian School. “Lakota Powwow Dance Styles.” www.stjo.org/site/PageServer?pagename=culture_powwow_styles (accessed July 9, 2014).

University of Nebraska State Museum and University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries. “Omaha Indian Heritage.” https://omahatribe.unl.edu/ (accessed July 9, 2014).

Research compiled by: Mariano M., Jenna R., and Shylene C.