Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Restoring the Ponca Tribe

-

Why was the issue of termination such an important one for both Native Americans and the federal government?

Ponca Tribe

-

When Congress decided to remove several northern tribes to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) in 1876, the Ponca were on the list. One reason is because a conflict between the Ponca and the Sioux/Lakota, who now claimed the land as their own by United States law, forced the United States to remove the Ponca from their own ancestral lands.

After inspecting the land that the U.S. Government offered for the Ponca’s new reservation and finding it unsuitable for agriculture, the Ponca chiefs decided against a move to the Indian Territory. When government officials came in early 1877 to move the Ponca to their new land, the chiefs refused, citing their earlier treaty. Most of the tribe refused and had to be moved by force. In their new location, the Ponca struggled with malaria, a shortage of food and the hot climate. One in four members died within the first year.

This was one of many government policies that affected Native culture in America. This webpage will tell the story of the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska's fight to regain its tribal status after it was taken away from them.

An 8 minute video in 2014 with interviews of Wanda LeRoy (Fred’s sister), Dr. Beth Ritter (Associate Professor of Anthropology & Native American Studies at UNO), and Rhonda Weston (Fred’s Daughter) about the Ponca tribe and the history of the contributions Fred LeRoy made to restore the tribe.

1800s to Termination

-

Chief Standing Bear was removed from his land and sent on the treacherous journey to the Ponca reservation in Oklahoma. On the journey to the reservation Standing Bear’s oldest son Bear Shield died. When Bear Shield was on his deathbed, Standing Bear promised to have him buried on the tribe's ancestral lands. In order to carry out his promise, Standing Bear left the reservation in Oklahoma and traveled back toward the Ponca homelands. He was arrested for going without the United States Government's permission and was confined at Fort Omaha. Many people took up his cause, and two prominent attorneys offered their services for free. Standing Bear filed a lawsuit challenging his arrest. In Standing Bear v. Crook (1879), held in Omaha, Nebraska, the United States District Court established for the first time that Native Americans are persons and that they have certain rights as well. This was an important civil rights case.

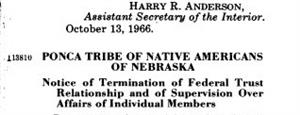

Chief Standing Bear was removed from his land and sent on the treacherous journey to the Ponca reservation in Oklahoma. On the journey to the reservation Standing Bear’s oldest son Bear Shield died. When Bear Shield was on his deathbed, Standing Bear promised to have him buried on the tribe's ancestral lands. In order to carry out his promise, Standing Bear left the reservation in Oklahoma and traveled back toward the Ponca homelands. He was arrested for going without the United States Government's permission and was confined at Fort Omaha. Many people took up his cause, and two prominent attorneys offered their services for free. Standing Bear filed a lawsuit challenging his arrest. In Standing Bear v. Crook (1879), held in Omaha, Nebraska, the United States District Court established for the first time that Native Americans are persons and that they have certain rights as well. This was an important civil rights case.After 1962 the tribal status of the Ponca was terminated. The termination policy of the United States government was a way to force assimilation onto the Poncas and other Native American tribes. Smaller tribes, like the Ponca, were terminated most often because they did not have as much power. There were other reasons for their termination as well. From the side of the Ponca, one of the reasons was that the young men from the tribe were moving away because they wanted to live the city life. When they moved away, the older Poncas were feeling hopeless of the future of their tribal traditions because if there were no younger generations to pass down the traditions, then their traditions would cease to exist. The United States Government terminated the tribe (Northern Ponca). It distributed its land by allotment to members and sold off extra land.

After Termination to Restoration

-

In 1965 after the termination of the Ponca Tribe, former members could not be called a tribe by the government. Former members of the Ponca Tribe were able to visit Native American Centers around the region, but they could not hold leadership positions. They lost their homes, dignity, pride, and family. After they were terminated they scattered all around the country from Alaska to Puerto Rico. Because they could not live on the reservation, they lived in cities and had difficulties finding jobs without government or traditional medical help. It was a very difficult to keep their traditions alive. Despite these challenges, the Ponca people continued to pass their culture down to future generations.

In 1986 after 21 years, Fred Leroy decided to restore the Ponca Tribe. He got the idea from his daughter, Rhonda. She asked why the Ponca Tribe was left out when she was doing a report for her Nebraska History class in the 4th grade. Leroy asked the Ponca people if they wanted to be restored as a tribe. Three hundred of the 442 members from 1965 Final Termination Roll favored being restored as a tribe. Leroy drafted out a petition for Ponca Tribe Restoration in 1986. In the summer of 1987, he received Bureau of Indian Affairs requirements to restore a terminated tribe to federal recognition. In order for the tribe to be restored, the United States Congress had to pass a law. After three years of LeRoy meeting with Senators, the law was passed by Congress.

In 1986 after 21 years, Fred Leroy decided to restore the Ponca Tribe. He got the idea from his daughter, Rhonda. She asked why the Ponca Tribe was left out when she was doing a report for her Nebraska History class in the 4th grade. Leroy asked the Ponca people if they wanted to be restored as a tribe. Three hundred of the 442 members from 1965 Final Termination Roll favored being restored as a tribe. Leroy drafted out a petition for Ponca Tribe Restoration in 1986. In the summer of 1987, he received Bureau of Indian Affairs requirements to restore a terminated tribe to federal recognition. In order for the tribe to be restored, the United States Congress had to pass a law. After three years of LeRoy meeting with Senators, the law was passed by Congress.

Post Restoration

-

On October 31, 1990, the United States Congress passed the Ponca Restoration Act. Now the Ponca people were federally recognized as a tribe, and along with that, the Ponca Tribe received federal benefits including healthcare and education again. However, they still did not have a reservation, so the tribe began building urban homes for the Ponca families. With federal money, they built forty houses in four different cities in Nebraska. Fred LeRoy, an advocate of the Ponca people, saw the needs of his people and built the Ponca Health and Wellness Center.

Today, it is named The Fred LeRoy Health and Wellness Center. It offers traditional medical, and modern medical and dental care, and it also offers social services. These services are offered to all Native Americans. The clinic currently has a sweat lodge that is used for holistic ceremonies to connect with the spirits, and Medicine Men visit and perform ceremonies. The clinic provides a sense of home and community for the Poncas.

The University of Nebraska-Omaha also honored Fred LeRoy by naming their annual pow-wow the Wambli Sapa Memorial Pow-Wow. Wambli Sapa was LeRoy's Native American name, meaning Black Eagle.

Additional Information

-

The Ponca Restoration Project provided a wonderful experience for the students to explore a topic that deserves more attention than The State of Nebraska and The United States Government have given it. It was a pleasure to witness the students explore, research their topic, interview important people, and create this website.

We would like to thank The Douglas County Historical Society, The Fred LeRoy Health and Wellness Center, and especially Wanda LeRoy, Dr. Beth Ritter, and Rhonda Weston for the contributions that they have made to The Ponca Restoration Project.

Student Reflections

-

"I enjoyed learning about the Ponca Tribe's culture and their lifestyle. I also enjoyed learning some of the stories from their tribe."

- Nicole A.

"I learned that investigating things can also help you find out more about history. I found an adventure through my curiosity about the Ponca People."- Adriana T.

"When I heard about this program I thought I was going to be sitting in a classroom and writing all day. But when I started the program it was exactly the opposite of what I thought because we went on field trips."- Sergio B.M.

Resources

-

Omaha World-Herald, “Busy Tribe Sets Sights on Clinic,”

Omaha World-Herald, “Ponca Tribe’s Revival Restores Link to History,” November 10, 1990

Omaha World-Herald, “Ponca Indians Regain Status as Tribe,” November 7, 1990.

Omaha World-Herald, “Ponca Tribe’s Clinic Plans to Mix Methods,” November 10, 1991

Omaha World-Herald, “Tribe Plans Housing in 4 Cities,” February 11, 1995

Omaha World-Herald, “For Nebraska Poncas, Being a Person Tops Being a Tribe,” October 21, 1962

Omaha World-Herald, “Poncas Asking For Tribe Status to be Restores,” June 11, 1989

Omaha World-Herald, “Tribe Buys Building for Clinic,” March 31 1997

Omaha World-Herald, “Ponca Indians Will Seek Restoration of Tribal Status,” May 24, 1988

Photo obtained from: www.poncatribe-ne.org

Photo obtained from: www.journalstar.com

Photo obtained from: http.digital.library.okstate.edu

Research compiled by: Adriana T., Nicole A., Sergio B.M.