Making Invisible Histories Visible

Page Navigation

- Making Invisible Histories Visible

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- iBooks on Omaha and Nebraska History for Primary Students

- Omaha Mapping Projects

-

African American Histories

- African American Artists

- African American Athletes & Facilities

- African American Churches

- African American Civil Rights Organizations - 1950s-1960s

- African American Civil Rights

- African American Contributions to Jazz, Gospel, Hip-Hop

- African American Dramatic Arts

- African American Education - Dorothy Eure & Lerlean Johnson

- African American Educators & Education

- African American Firefighters

- African American Homesteaders

- African American Law Enforcement

- African American Migration to Omaha

- African American Musicians of Omaha

- African American Newspapers

- African American Owned Businesses

- African American Politicians

- African American Social Life

- African American Workers at Omaha's Railroads & Stockyards

- African American Workers at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hastings

- African Americans in the Civil War

- African Americans in Vietnam

- Charles B. Washington - Journalist and Civil Rights Leader

- Elizabeth Davis Pittman - Lawyer/Judge

- Green Book Omaha

- Marlin Briscoe - Professional Football Player

- Native Omaha Days

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- Sen. Edward Danner - Politician & Civil Rights Activist

- Sudanese Refugees

- Tuskegee Airmen

- European and Asian Immigrant Histories

-

Historic Neighborhoods & Buildings

- 24th and Binney/Wirt/Spencer Streets

- 24th and Lake Streets

- Central Park Neighborhood - 42nd and Grand Avenue

- Dahlman Neighborhood - 10th and Hickory Streets

- Hartman Addition Neighborhood - 16th and Williams Streets

- Indian Hills/Southside Terrace Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Jefferson Square Neighborhood - 16th and Chicago Streets

- Long Neighborhood - 24th and Clark Streets

- Orchard Hill Neighborhood - 40th and Hamilton Streets

- Smithfield Neighborhood - 24th and Ames Avenue

- St. Mary's Neighborhood - 30th and Q Streets

- Latino Histories

- Music Histories

-

Native American Histories

- Black Elk and John G. Niehardt

- Chief Standing Bear and Susette La Flesche Tibbles

- Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte - Native American Doctor

- Native American Education and Boarding Schools

- Native Americans in the Military

- Pre-statehood Interaction of Native Americans and Europeans

- Preserving Native American Tradition

- Restoring the Ponca Tribe

- The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s

- The Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- The Omaha Native American Indian Tribe

- OPS Elementary School History

- Redlining in Omaha

- Nebraska's Role in the Underground Railroad

- The 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

African American Homesteaders

-

In what ways was African American migration to the Great Plains unique?

"…A way of life is not short…" - Ava Speese Day, a descendent of the Moses Speese Family

Early African American Settlers in Nebraska

-

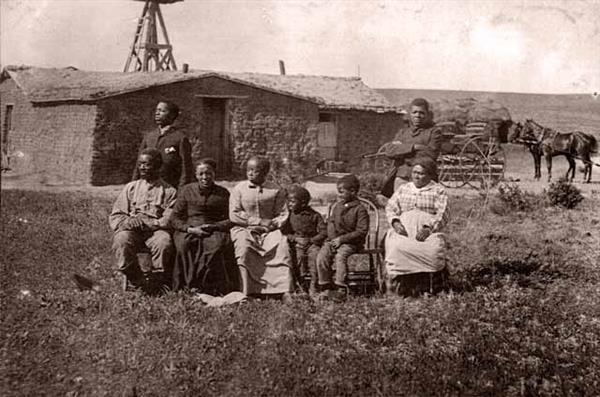

In our research, we learned about how African American settlers came to Nebraska. Even though African Americans have lived in parts of Nebraska since the 1850s, around 1904, a new wave of settlers arrived in Nebraska. Black settlers wanted to be able to get land of their own, and thanks to the Kinkaid Act, land in the “Sand Hills” area was available. The Kinkaid Act of 1904, and the Homestead Act of 1862 before, allowed Black families to go into Nebraska in search for land. Settlers heard Nebraska was a safe place for Blacks to go, and it also had millions of acres of free land. When settlers first arrived, they struggled to look for shelter. Since there was a lack of trees in Nebraska, sod houses were used for shelter. If the weather was too hot or too cold, growing crops became difficult. Settler life wasn't always pleasant. Many settlers were poor and could not afford many extras in life. Mother Nature was cruel in areas of Nebraska, starting wild prairie fires that destroyed everything in its path. The early Black settlers didn't always have it easy, and the following is a look into what life was like for these forgotten members of our state’s history.

A 9 minute video produced in 2012 with an interview with Edgar Hicks. Hicks is a historian, an executive in the grain industry, and has done a lot of research on early Black settlers in Nebraska and their ties to agriculture.

-

The Moses Speese Family was one of the most well-known Black homestead groups in Nebraska. They settled in Cherry County, Nebraska, where they claimed their land. Moses and his brother, Jeremiah Shores, were separated during slavery and reunited in Nebraska. They constructed sod houses and worked the land. Moses's son, John, said about his family, "What a poor colored man can accomplish every man in the east can do, with vim, economy, and integrity."

Black Homesteaders and City Dwellers

-

One of the first groups of Black homesteaders came from Canada and arrived in Dawson County, Nebraska, in 1880. This group, led by Charles Meehan, was used to the cold winters and conditions of Nebraska, unlike other homesteaders who returned South because of unfavorable conditions. These skilled, educated, and well-off homesteaders thrived in Nebraska.

Clem Deaver was another one of the first African Americans to settle in Nebraska. He acquired his land through the Kinkaid Act of 1904. Deaver was vital in bringing many other Black homesteaders to Cherry County, one of the first all-Black homesteads in Nebraska. Deaver reached out to Charles Meehan's group in Dawson County. At first, Meehan did not want to leave the land, but after two years of drought there, Deaver convinced him to move to Cherry County.

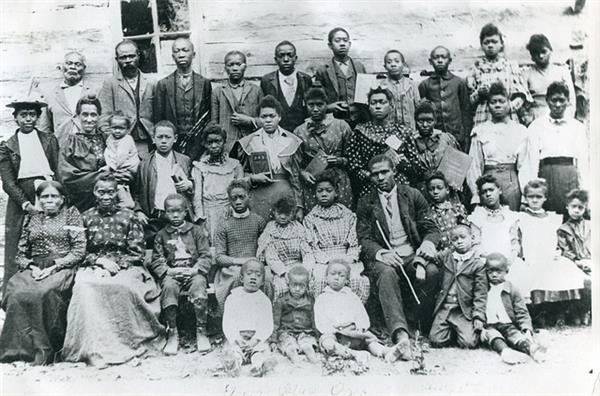

These two Black homesteader groups settled in what was originally named DeWitty, Nebraska. In 1910, 24 Black families had claimed 14,000 acres of land near DeWitty. Just 10 years later, more than 185 African Americans had claimed over 40,000 acres of land around DeWitty. This was the “largest and most permanent” African American town in Nebraska. DeWitty had a post office, a barbershop, three schools, and even a baseball team.

But eventually, the good times at DeWitty came to an end. The Black homesteaders were faced with crop failures and droughts. They sold their land to banks, realizing that the land in Cherry County was not good for raising crops. By the 1930s, many Black homesteaders had moved off of farms in Nebraska. Cities like Lincoln and Omaha became home to about 90 percent of Blacks in Nebraska.

Even though there were a lot of Black homesteaders that lived on farms, we cannot forget about Black citizens that lived in Nebraska’s cities. The large population of African Americans in Omaha made it the third-largest African American population in the western part of the country. Many Black settlers in Nebraska had jobs in the city. In some instances when white unions called strikes, Black workers were available to fill in. If you look closely into the history of the early Black settlers, you will notice that their daily lives became more similar to our lives today. They built community institutions like churches, barbershops, newspapers, and more. African Americans also made connections with other ethnic groups.

Daily Life

-

People often think that times before were like times today, but that is very wrong. The daily lives of early Black settlers in Nebraska were very different from the lives we live today.

Crops commonly grown in a Black settler family included beans, corn, pumpkins, squash, melons, sunflower seeds, chokecherries, wild grapes, and plums. Some foods that were made with the crops listed above are things like corn soup, dried beef, cow stomach, dried fruits and vegetables, and buttermilk. Dinner was the large meal of the day and on most days, corn was served. Families raised pigs, and cows were used for their milk, not meat. Lunch was smaller than what we eat today. A common lunch for settlers included cornbread and syrup. Early settlers didn't have many advanced things like we have today. There weren't lunch pails, boxes, containers, or any plastic items in the past. When kids carried their lunches, they carried them in big tin cans.

In almost every household, settlers made much of their clothing except for shoes, stockings, coats, and underwear. Most of their clothing was made from flour sacks or burlap material. They also wore many hand-me-downs from the oldest child to the youngest. Clothes were passed down and patched up if they got worn. In our culture today, many people view homemade clothes as a downer.

Chores played a major part for the children of early Black settlers. Some of the chores children did were milking cows, hoarding coal, banking the fire, picking up cow chips, fighting tumbleweeds, pulling hogweed, paisley, and young thistles, feeding chickens, picking potato bugs, and scrubbing clothes. Materials used to do these chores were things like washboards, pails, knives, and “mowing machines” (tractors). Some children spent their whole day doing chores around the homestead. These chores are very rare for today's youth unless you live on a farm or ranch.

Buffalo Soldiers and Cowboys

-

The Buffalo Soldiers were African Americans who were offered labor positions in the U.S. Army by the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry. Nearly 180,000 of them fought in the Civil War against the Confederacy. More than 33,000 of them sacrificed themselves to end slavery. Though they were fighting for their country in the Civil War, they had to fight for their freedom also. Some of the first Nebraska Buffalo Soldiers were found at Fort Robinson (Crawford, Nebraska). They were stationed there from 1887 to 1906. There was so much racial tension at Fort Robinson that two members of the Ninth Cavalry lost their careers. One of the members was an African American named Henry V. Plummer. He was a lieutenant and a commissioned officer in the U.S. Army at the time. He was charged with sending an inflammatory article and for being drunk in public. The other ex-cavalry soldier was Sergeant Barney McKay. He was court-martialed and charged with bringing a pamphlet threatening retaliation against Crawford for the treatment of another ex-cavalry officer, James Diggs.

Cowboys were animal herders who moved tons of cattle across a thousand miles of rough mosquito-covered land. They did a lot of traveling along the East-West rail lines that crossed Nebraska. The cowboys went on three major trails which took them across Nebraska. So many passed through Ogallala that it became known as the “cowboy capital”. Cowboys came across lots of cattle, so they often had meals with beef, beans, and biscuits. They made their meals from Dutch ovens, which was very common for cowboys in the 1890s. Nat Love was a Black cowboy born in Tennessee in 1854. He was one of many former slaves who became independent workers in the West. Nat was hired by a Black cowboy named Bronco Jim while he was on his way to Dodge City, Kansas. Love was only 15 at the time. Jim gave him supplies and he branded calves for 30 dollars a month. At one point, Nat was captured by Native Americans but he eventually returned to his life as a cowboy. Another Nebraskan cowboy was James Kelly. He rode with the Print Olive Gang near Ogallala, Nebraska. He was a part of the gunfighting culture of the American West but was also set apart by his race. White cowboys called him "Nigger Kelly."

Early Settlers

-

Some of the first settlers to come to Omaha were African Americans. Some of their ancestors fought for America, most recently in the Civil War. After the Civil War, they moved to Nebraska to gain their own land. Though their ancestors had little education, they could read and write. The education they had didn't make them successful because of discrimination. It began in the 1860s when many free Negroes came to Nebraska. Many Black settlers came to Nebraska for jobs in the packing houses and railroads. They really lived a hard life. Because of their skin being different shades of brown, whites judged them by their color. The settlers grew all of their food, which made it harder for them to survive because they had the worst land in Nebraska. To make it to the next day and have a meal to eat was a big challenge for them. This was an everyday thing for them to survive. One of the most well-known Black settler groups were members of the Speese family. The father of the Speese family, Moses, was a former slave who had very successful children, including a lawyer and minister. In 1884, I.B. Burton, a Nebraskan who wrote to a Black newspaper in Washington, D.C., described how settlers pooled resources and urged people to follow their example. He was once quoted, “A large company can emigrate and purchase railroad lands for about half of what it would cost single persons or single families. . . . Windmills are indispensable in the far west, and one windmill could be made to answer four or five farmers--each having an interest in it.” Robert Ball Anderson, the son of a slave in Green County, Kentucky, joined the Union army in 1864. Six years later, he homesteaded 80 acres of land in Nebraska. In 1871, he stopped farming and started over in the Nebraska panhandle. Later, he moved and built a two-room sod house for shelter at the homestead claim he took in Box Butte County. Anderson eventually gained 2,080 acres of land and became the largest Black landholder in Nebraska.

Additional Information

-

The students working on this project did a great job of going beyond merely showing that African Americans were present on the Great Plains. Their work in the late 19th and early 20th century highlights three important themes in the history of the Black West: multiple migrations, the enduring Black community institutions and cultural life, and the persistence of racial inequality.

First, it is important to remember that African American history has seen a number of migrations and many Black people moved more than once in their lifetime. The students point to examples of African Americans arriving in Nebraska not only from the U.S. South, like Nat Love from Tennessee, but also Canada, as the Meehan group did. Moreover, they show that a number of African Americans migrated once again from the rural Great Plains to urban areas as many left their farms in the 1930s. The students also explore reasons for migration. They consider opportunities, like the possibility of success, similar to that of the Speese family, which found prosperity on the plains. But, they also draw attention to challenges, including the difficulty of daily life and unwelcoming weather.

Second, the students’ work highlights the importance of communities in both promoting migration and sustaining African American social and cultural life in unfamiliar territory. African Americans often migrated together, like the group led by Charles Meehan. In other instances, they encouraged fellow African Americans to relocate to areas of the West that had existing Black populations. Clem Deaver’s efforts to bring Black homesteaders to Cherry County are an excellent example of this. Once formed, these communities sustained Black social and cultural life, from baseball teams to barbershops, even in spite of small numbers.

Third, the students showed that, though many Blacks believed in the possibility of a more equal society in the West, racial inequality persisted. In rural areas, African Americans might have found themselves farming the least desirable land or working among white cowboys who called them “niggers.” In urban areas, some employers only offered Black workers job opportunities when White workers were on strike. At military posts, racial tensions damaged morale and unit cohesion. The students also look beyond Black-White relations to mention interactions with Native Americans. In the end, all of this work leads us to a better understanding of African American life in the West.

2012 MIHV Project

Related Projects

-

"I really had a great time at this program and learned so much about Omaha’s history. Without “Making Invisible Histories Visible,” I wouldn’t know anything about Omaha history, and thought Omaha was just a normal place with no history. I’ve met a lot of guest speakers that grew up in Omaha. We also took Ollie The Trolley bus ride and went to Will Brown’s gravesite at Potters Field. I really learned a lot that day about Omaha history. If I could do this program again, I would."

- Marquis C.

"Before I came to this program I didn’t even know Nebraska even had black settlers. I learned that in the past, it was not always easy, and food was not always there. This showed me that the people of today need to appreciate the things we have way more than we do."- Ky’Aira R.

"I really enjoyed this program. I learned about many things I didn’t even know existed. Joining this program gave me the experience of having fun while working hard with history at the same time. What really surprised me was that there were black cowboys in Nebraska. Before this program, I didn’t even know black cowboys were real. Omaha has a big history and I enjoyed learning about it."- Jordan J.

Resources

-

“Black in Nebraska timeline.” The Lincoln Journal Star, May 16, 2008. https://journalstar.com/news/local/article_3f0c8ee2-2bc1-57d6-93f5-7c7e51e9fb4a.html

Alberts, Frances Jacobs, ed. Sod House Memories. Henderson, NE: Sod House Society, 1972.

Calloway, Bertha W. and Alonzo N. Smith. Visions of Freedom on the Great Plains: An Illustrated History of African Americans in Nebraska. Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company Publishers, 1998.

Garner, Carla W. “DeWitty/Audacious, Nebraska (1908 - ).” BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/?q=aaw/dewitty-audacious-nebraska-1908

Johansen, Gary. “Black Homesteaders.” Sunday World-Herald Magazine of the Midlands (March, 15, 1970): 18-24.

Nebraska State Historical Society. “Nebraska’s First Farmers. Nebraska Trailblazer 4. Undated.

______. “Early Settlers.” Nebraska Trailblazer 7. Undated.

______. “What’s For Lunch? Food Choices of the 1890s. Nebraska Trailblazer 12. Undated.

Schlissel, Lillian. Black Frontiers: A History of African American Heroes in the Old West. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Taylor, Quintard. In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1998.

Williams, Jean. “Nebraska’s Negro Homesteaders.” NebraskaLand (February, 1969): 30-33, 49-50.

Research compiled by Jared Leighton

Special thanks to Mr. Edgar Hicks for his assistance on this project.

Research compiled by: Ky'Aira R., Jordan J., Marquis C., Jade R., & Burke B.